Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

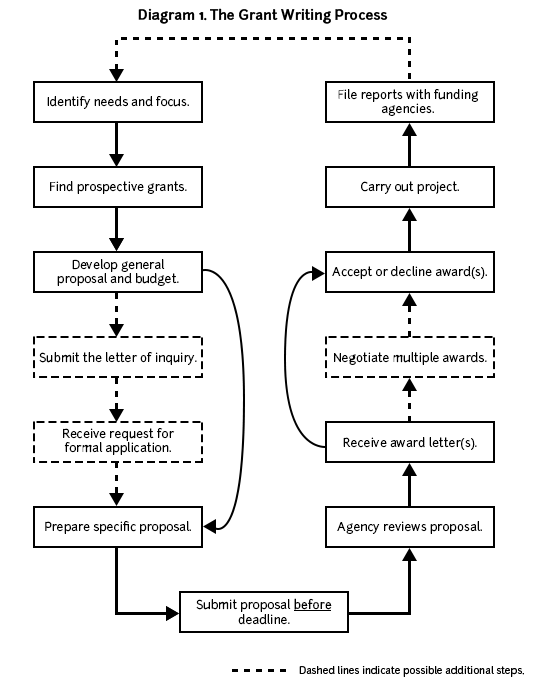

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.

Final decisions about which proposals are funded often come down to whether the proposal convinces the reviewer that the research project is well planned and feasible and whether the investigators are well qualified to execute it. Throughout the proposal, be as explicit as possible. Predict the questions that the reviewer may have and answer them. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) note that reviewers read with three questions in mind:

- What are we going to learn as a result of the proposed project that we do not know now? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is it worth knowing? (significance)

- How will we know that the conclusions are valid? (criteria for success) (2)

Be sure to answer these questions in your proposal. Keep in mind that reviewers may not read every word of your proposal. Your reviewer may only read the abstract, the sections on research design and methodology, the vitae, and the budget. Make these sections as clear and straightforward as possible.

The way you write your grant will tell the reviewers a lot about you (Reif-Lehrer 82). From reading your proposal, the reviewers will form an idea of who you are as a scholar, a researcher, and a person. They will decide whether you are creative, logical, analytical, up-to-date in the relevant literature of the field, and, most importantly, capable of executing the proposed project. Allow your discipline and its conventions to determine the general style of your writing, but allow your own voice and personality to come through. Be sure to clarify your project’s theoretical orientation.

Develop a general proposal and budget

Because most proposal writers seek funding from several different agencies or granting programs, it is a good idea to begin by developing a general grant proposal and budget. This general proposal is sometimes called a “white paper.” Your general proposal should explain your project to a general academic audience. Before you submit proposals to different grant programs, you will tailor a specific proposal to their guidelines and priorities.

Organizing your proposal

Although each funding agency will have its own (usually very specific) requirements, there are several elements of a proposal that are fairly standard, and they often come in the following order:

- Introduction (statement of the problem, purpose of research or goals, and significance of research)

Literature review

- Project narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes or deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination)

- Budget and budget justification

Format the proposal so that it is easy to read. Use headings to break the proposal up into sections. If it is long, include a table of contents with page numbers.

The title page usually includes a brief yet explicit title for the research project, the names of the principal investigator(s), the institutional affiliation of the applicants (the department and university), name and address of the granting agency, project dates, amount of funding requested, and signatures of university personnel authorizing the proposal (when necessary). Most funding agencies have specific requirements for the title page; make sure to follow them.

The abstract provides readers with their first impression of your project. To remind themselves of your proposal, readers may glance at your abstract when making their final recommendations, so it may also serve as their last impression of your project. The abstract should explain the key elements of your research project in the future tense. Most abstracts state: (1) the general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be as explicit as possible in your abstract. Use statements such as, “The objective of this study is to …”

Introduction

The introduction should cover the key elements of your proposal, including a statement of the problem, the purpose of research, research goals or objectives, and significance of the research. The statement of problem should provide a background and rationale for the project and establish the need and relevance of the research. How is your project different from previous research on the same topic? Will you be using new methodologies or covering new theoretical territory? The research goals or objectives should identify the anticipated outcomes of the research and should match up to the needs identified in the statement of problem. List only the principle goal(s) or objective(s) of your research and save sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Many proposals require a literature review. Reviewers want to know whether you’ve done the necessary preliminary research to undertake your project. Literature reviews should be selective and critical, not exhaustive. Reviewers want to see your evaluation of pertinent works. For more information, see our handout on literature reviews .

Project narrative

The project narrative provides the meat of your proposal and may require several subsections. The project narrative should supply all the details of the project, including a detailed statement of problem, research objectives or goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes or deliverables, and evaluation and dissemination of the research.

For the project narrative, pre-empt and/or answer all of the reviewers’ questions. Don’t leave them wondering about anything. For example, if you propose to conduct unstructured interviews with open-ended questions, be sure you’ve explained why this methodology is best suited to the specific research questions in your proposal. Or, if you’re using item response theory rather than classical test theory to verify the validity of your survey instrument, explain the advantages of this innovative methodology. Or, if you need to travel to Valdez, Alaska to access historical archives at the Valdez Museum, make it clear what documents you hope to find and why they are relevant to your historical novel on the ’98ers in the Alaskan Gold Rush.

Clearly and explicitly state the connections between your research objectives, research questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and outcomes. As the requirements for a strong project narrative vary widely by discipline, consult a discipline-specific guide to grant writing for some additional advice.

Explain staffing requirements in detail and make sure that staffing makes sense. Be very explicit about the skill sets of the personnel already in place (you will probably include their Curriculum Vitae as part of the proposal). Explain the necessary skill sets and functions of personnel you will recruit. To minimize expenses, phase out personnel who are not relevant to later phases of a project.

The budget spells out project costs and usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with the budget detailed as line items and a budget narrative (also known as a budget justification) that explains the various expenses. Even when proposal guidelines do not specifically mention a narrative, be sure to include a one or two page explanation of the budget. To see a sample budget, turn to Example #1 at the end of this handout.

Consider including an exhaustive budget for your project, even if it exceeds the normal grant size of a particular funding organization. Simply make it clear that you are seeking additional funding from other sources. This technique will make it easier for you to combine awards down the road should you have the good fortune of receiving multiple grants.

Make sure that all budget items meet the funding agency’s requirements. For example, all U.S. government agencies have strict requirements for airline travel. Be sure the cost of the airline travel in your budget meets their requirements. If a line item falls outside an agency’s requirements (e.g. some organizations will not cover equipment purchases or other capital expenses), explain in the budget justification that other grant sources will pay for the item.

Many universities require that indirect costs (overhead) be added to grants that they administer. Check with the appropriate offices to find out what the standard (or required) rates are for overhead. Pass a draft budget by the university officer in charge of grant administration for assistance with indirect costs and costs not directly associated with research (e.g. facilities use charges).

Furthermore, make sure you factor in the estimated taxes applicable for your case. Depending on the categories of expenses and your particular circumstances (whether you are a foreign national, for example), estimated tax rates may differ. You can consult respective departmental staff or university services, as well as professional tax assistants. For information on taxes on scholarships and fellowships, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/ .

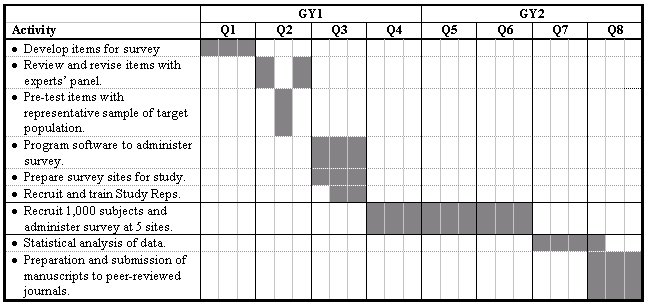

Explain the timeframe for the research project in some detail. When will you begin and complete each step? It may be helpful to reviewers if you present a visual version of your timeline. For less complicated research, a table summarizing the timeline for the project will help reviewers understand and evaluate the planning and feasibility. See Example #2 at the end of this handout.

For multi-year research proposals with numerous procedures and a large staff, a time line diagram can help clarify the feasibility and planning of the study. See Example #3 at the end of this handout.

Revising your proposal

Strong grant proposals take a long time to develop. Start the process early and leave time to get feedback from several readers on different drafts. Seek out a variety of readers, both specialists in your research area and non-specialist colleagues. You may also want to request assistance from knowledgeable readers on specific areas of your proposal. For example, you may want to schedule a meeting with a statistician to help revise your methodology section. Don’t hesitate to seek out specialized assistance from the relevant research offices on your campus. At UNC, the Odum Institute provides a variety of services to graduate students and faculty in the social sciences.

In your revision and editing, ask your readers to give careful consideration to whether you’ve made explicit the connections between your research objectives and methodology. Here are some example questions:

- Have you presented a compelling case?

- Have you made your hypotheses explicit?

- Does your project seem feasible? Is it overly ambitious? Does it have other weaknesses?

- Have you stated the means that grantors can use to evaluate the success of your project after you’ve executed it?

If a granting agency lists particular criteria used for rating and evaluating proposals, be sure to share these with your own reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

Jet travel $6,100 This estimate is based on the commercial high season rate for jet economy travel on Sabena Belgian Airlines. No U.S. carriers fly to Kigali, Rwanda. Sabena has student fare tickets available which will be significantly less expensive (approximately $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788 Based on the Fulbright-Hays Maintenance Allowances published in the grant application guide.

Research assistant/translator $4,800 The research assistant/translator will be a native (and primary) speaker of Kinya-rwanda with at least a four-year university degree. They will accompany the primary investigator during life history interviews to provide assistance in comprehension. In addition, they will provide commentary, explanations, and observations to facilitate the primary investigator’s participant observation. During the first phase of the project in Kigali, the research assistant will work forty hours a week and occasional overtime as needed. During phases two and three in rural Rwanda, the assistant will stay with the investigator overnight in the field when necessary. The salary of $400 per month is based on the average pay rate for individuals with similar qualifications working for international NGO’s in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200 The primary investigator and research assistant will need regular transportation within Kigali by bus and taxi. The average taxi fare in Kigali is $6-8 and bus fare is $.15. This figure is based on an average of $10 per day in transportation costs during the first project phase.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000 Project personnel will also require regular transportation between rural field sites. If it is not possible to remain overnight, daily trips will be necessary. The average rental rate for a 4×4 vehicle in Rwanda is $130 per day. This estimate is based on an average of $50 per day in transportation costs for the second and third project phases. These costs could be reduced if an arrangement could be made with either a government ministry or international aid agency for transportation assistance.

Email $720 The rate for email service from RwandaTel (the only service provider in Rwanda) is $60 per month. Email access is vital for receiving news reports on Rwanda and the region as well as for staying in contact with dissertation committee members and advisors in the United States.

Audiocassette tapes $400 Audiocassette tapes will be necessary for recording life history interviews, musical performances, community events, story telling, and other pertinent data.

Photographic & slide film $100 Photographic and slide film will be necessary to document visual data such as landscape, environment, marriages, funerals, community events, etc.

Laptop computer $2,895 A laptop computer will be necessary for recording observations, thoughts, and analysis during research project. Price listed is a special offer to UNC students through the Carolina Computing Initiative.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00 NUD*IST, “Nonnumerical, Unstructured Data, Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing,” is necessary for cataloging, indexing, and managing field notes both during and following the field research phase. The program will assist in cataloging themes that emerge during the life history interviews.

Administrative fee $100 Fee set by Fulbright-Hays for the sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

Example #3: project timeline in chart format.

Some closing advice

Some of us may feel ashamed or embarrassed about asking for money or promoting ourselves. Often, these feelings have more to do with our own insecurities than with problems in the tone or style of our writing. If you’re having trouble because of these types of hang-ups, the most important thing to keep in mind is that it never hurts to ask. If you never ask for the money, they’ll never give you the money. Besides, the worst thing they can do is say no.

UNC resources for proposal writing

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Holloway, Brian R. 2003. Proposal Writing Across the Disciplines. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Levine, S. Joseph. “Guide for Writing a Funding Proposal.” http://www.learnerassociates.net/proposal/ .

Locke, Lawrence F., Waneen Wyrick Spirduso, and Stephen J. Silverman. 2014. Proposals That Work . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Przeworski, Adam, and Frank Salomon. 2012. “Some Candid Suggestions on the Art of Writing Proposals.” Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrc-cdn2/art-of-writing-proposals-dsd-e-56b50ef814f12.pdf .

Reif-Lehrer, Liane. 1989. Writing a Successful Grant Application . Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wiggins, Beverly. 2002. “Funding and Proposal Writing for Social Science Faculty and Graduate Student Research.” Chapel Hill: Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science. 2 Feb. 2004. http://www2.irss.unc.edu/irss/shortcourses/wigginshandouts/granthandout.pdf.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step Guide

How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step Guide

Table of Contents

Writing a grant proposal is an essential skill for researchers, non-profit organizations, and businesses seeking funding for projects or programs. A well-prepared grant proposal not only increases your chances of securing funding but also demonstrates your commitment and capability to execute your proposed project. This article provides a detailed, step-by-step guide to crafting a successful grant proposal.

How To Write A Grant Proposal

Step 1: understand the funding opportunity.

Before starting your proposal, research potential funding sources to identify those that align with your project’s goals. Review the funder’s guidelines, priorities, and eligibility criteria carefully. This ensures your proposal is tailored to the funder’s interests and increases the likelihood of success.

- Example : If a foundation focuses on environmental sustainability, tailor your proposal to emphasize the environmental benefits of your project.

Step 2: Define Your Project

Clearly articulate your project’s purpose, goals, and objectives. This step involves answering critical questions:

- What problem does your project address?

- Who will benefit from it?

- How will you achieve your goals?

- Example : If applying for a grant to improve literacy, define the specific population (e.g., adults in rural areas) and outline measurable objectives such as increasing reading comprehension levels by 20% within a year.

Step 3: Develop a Strong Title and Executive Summary

Your proposal title and executive summary create the first impression. The title should be concise yet descriptive, while the executive summary should provide a snapshot of the entire proposal, highlighting the problem, solution, and expected outcomes.

- Example of a Title : “Bridging the Gap: A Community-Based Literacy Program for Rural Adults.”

- Executive Summary : In a paragraph, summarize the problem (low literacy rates), the proposed solution (community workshops), the target population (adults in rural areas), and the expected outcomes (improved literacy skills).

Step 4: Write the Statement of Need

This section explains the problem your project seeks to solve. Use data, research, and testimonials to provide evidence of the need for your project. Convince the funder that the issue is significant and that your project is a viable solution.

- Example : “According to the National Literacy Survey (2023), 30% of adults in rural areas lack basic reading skills. This gap affects employment opportunities, civic engagement, and quality of life. Our proposed program addresses this critical need through accessible community workshops.”

Step 5: Outline Goals and Objectives

Differentiate between goals (broad, long-term outcomes) and objectives (specific, measurable steps to achieve goals).

- Example of a Goal : Improve adult literacy in rural areas.

- Conduct 50 literacy workshops within 12 months.

- Enroll 300 participants in the program.

- Achieve a 20% increase in literacy test scores among participants.

Step 6: Describe Your Methods

Detail the activities and strategies you will use to achieve your objectives. Include information on timelines, resources, and personnel involved. This section should demonstrate that your approach is feasible and well-planned.

- Example : “The program will employ trained educators to conduct weekly workshops using evidence-based teaching methods. Participants will receive free materials, including workbooks and digital tools. Workshops will be held at accessible community centers.”

Step 7: Create a Budget and Justification

Provide a detailed budget that includes all costs associated with the project, such as personnel, equipment, materials, and administrative expenses. Include a budget justification explaining why each expense is necessary and reasonable.

- Educator salaries: $20,000

- Workshop materials: $5,000

- Venue rental: $3,000

- Administrative costs: $2,000

Step 8: Develop a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

Explain how you will track the progress and effectiveness of your project. Include specific metrics and methods for data collection, analysis, and reporting.

- Example : “We will use pre- and post-program literacy assessments to measure participant progress. Monthly feedback surveys will capture participant satisfaction and identify areas for improvement.”

Step 9: Write the Organizational Background

Provide information about your organization’s history, mission, and past successes. Highlight your experience and capacity to execute the proposed project effectively.

- Example : “Since 2010, our organization has implemented over 25 community education programs, reaching more than 5,000 individuals. Our experienced team of educators and volunteers ensures program success.”

Step 10: Include Supporting Documents

Attach any required documents, such as:

- Letters of support or commitment from partners.

- Organizational budget and financial statements.

- Resumes of key personnel.

- Proof of tax-exempt status (for non-profits).

Step 11: Review and Revise

Before submission, review your proposal for clarity, consistency, and alignment with the funder’s guidelines. Seek feedback from colleagues or mentors to identify areas for improvement.

- Pro Tip : Use proofreading tools to ensure your proposal is free of grammatical errors and typos.

Best Practices for Writing a Grant Proposal

- Align with Funder’s Priorities : Demonstrate that your project fits the mission and goals of the funding organization.

- Be Clear and Concise : Avoid jargon and ensure your proposal is easy to understand.

- Focus on Outcomes : Highlight the tangible benefits and impacts of your project.

- Use Evidence : Support your claims with data, research, and testimonials.

- Maintain Professionalism : Ensure the proposal is well-organized, visually appealing, and free of errors.

Example of a Grant Proposal Outline

- Title Page : Include the project title, applicant name, and contact details.

- Executive Summary : Summarize the project in 1–2 paragraphs.

- Statement of Need : Explain the problem and provide supporting evidence.

- Goals and Objectives : Define what the project aims to achieve.

- Methods : Detail the activities, timeline, and resources.

- Budget and Justification : Include a clear breakdown of costs.

- Evaluation Plan : Describe how you will measure success.

- Organizational Background : Provide information about your organization.

- Appendices : Attach supporting documents.

Writing a grant proposal requires careful planning, research, and attention to detail. By following this step-by-step guide, you can craft a compelling proposal that effectively communicates your project’s value and aligns with the funder’s goals. With a well-prepared grant proposal, you increase your chances of securing the funding needed to bring your project to life.

- Geever, J. C. (2012). The Foundation Center’s Guide to Proposal Writing (6th ed.). The Foundation Center.

- Miner, J., & Miner, L. E. (2018). Proposal Planning & Writing (6th ed.). Greenwood.

- Hall, M. R. (2021). How to Write a Grant Proposal . Wiley.

- Karsh, E., & Fox, A. S. (2019). The Only Grant-Writing Book You’ll Ever Need (5th ed.). Basic Books.

- Toriello, P. J., & Blevins, C. A. (2020). “Grant Writing: Strategies for Developing Winning Proposals.” Journal of Social Work Education , 56(1), 76-88.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Research Proposal – Types, Template and Example

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a grant proposal: a step-by-step guide

What is a grant proposal?

Why should you write a grant proposal, format of a grant proposal, how to write a grant proposal, step 1: decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process, step 2: plan and research your project, preliminary research for your grant proposal, questions to ask yourself as you plan your grant proposal, developing your grant proposal, step 3: write the first draft of your grant proposal, step 4: get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly, step 5: prepare to submit your grant proposal, what happens after submitting the grant proposal, final thoughts, other useful sources for writing grant proposals, frequently asked questions about writing grant proposals, related articles.

You have a vision for a future research project, and want to share that idea with the world.

To achieve your vision, you need funding from a sponsoring organization, and consequently, you need to write a grant proposal.

Although visualizing your future research through grant writing is exciting, it can also feel daunting. How do you start writing a grant proposal? How do you increase your chances of success in winning a grant?

But, writing a proposal is not as hard as you think. That’s because the grant-writing process can be broken down into actionable steps.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to grant-writing that includes researching the application process, planning your research project, and writing the proposal. It is written from extensive research into grant-writing, and our experiences of writing proposals as graduate students, postdocs, and faculty in the sciences.

A grant proposal is a document or collection of documents that outlines the strategy for a future research project and is submitted to a sponsoring organization with the specific goal of getting funding to support the research. For example, grants for large projects with multiple researchers may be used to purchase lab equipment, provide stipends for graduate and undergraduate researchers, fund conference travel, and support the salaries of research personnel.

As a graduate student, you might apply for a PhD scholarship, or postdoctoral fellowship, and may need to write a proposal as part of your application. As a faculty member of a university, you may need to provide evidence of having submitted grant applications to obtain a permanent position or promotion.

Reasons for writing a grant proposal include:

- To obtain financial support for graduate or postdoctoral studies;

- To travel to a field site, or to travel to meet with collaborators;

- To conduct preliminary research for a larger project;

- To obtain a visiting position at another institution;

- To support undergraduate student research as a faculty member;

- To obtain funding for a large collaborative project, which may be needed to retain employment at a university.

The experience of writing a proposal can be helpful, even if you fail to obtain funding. Benefits include:

- Improvement of your research and writing skills

- Enhancement of academic employment prospects, as fellowships and grants awarded and applied for can be listed on your academic CV

- Raising your profile as an independent academic researcher because writing proposals can help you become known to leaders in your field.

All sponsoring agencies have specific requirements for the format of a grant proposal. For example, for a PhD scholarship or postdoctoral fellowship, you may be required to include a description of your project, an academic CV, and letters of support from mentors or collaborators.

For a large research project with many collaborators, the collection of documents that need to be submitted may be extensive. Examples of documents that might be required include a cover letter, a project summary, a detailed description of the proposed research, a budget, a document justifying the budget, and the CVs of all research personnel.

Before writing your proposal, be sure to note the list of required documents.

Writing a grant proposal can be broken down into three major activities: researching the project (reading background materials, note-taking, preliminary work, etc.), writing the proposal (creating an outline, writing the first draft, revisions, formatting), and administrative tasks for the project (emails, phone calls, meetings, writing CVs and other supporting documents, etc.).

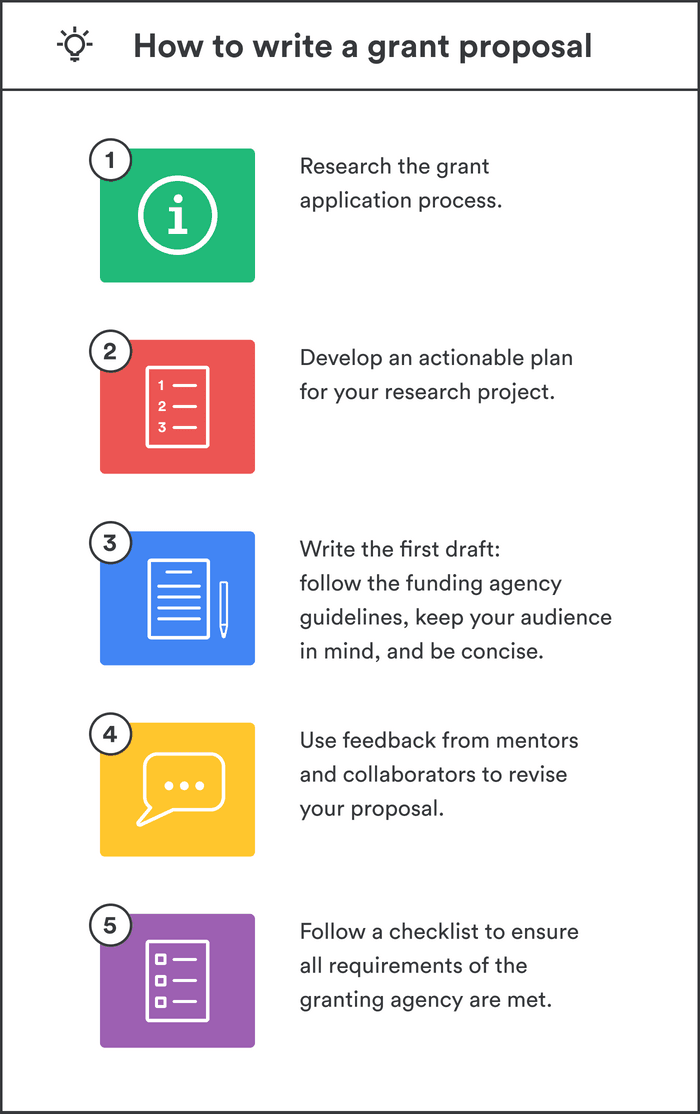

Below, we provide a step-by-step guide to writing a grant proposal:

- Decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process

- Plan and research your project

- Write the first draft of your grant proposal

- Get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly

- Prepare to submit your grant proposal

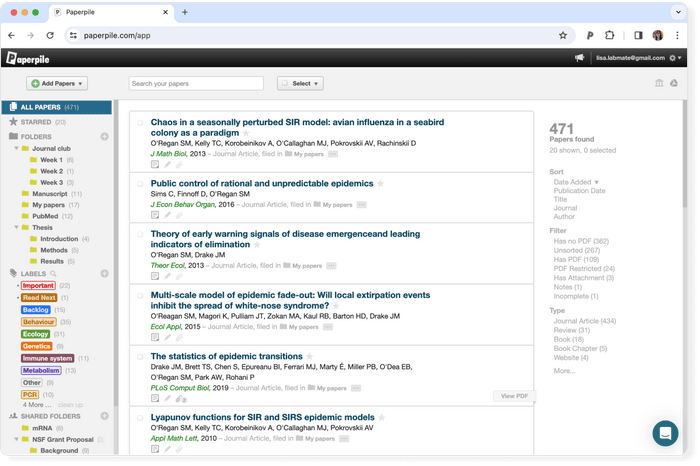

- Start early. Begin by searching for funding opportunities and determining requirements. Some sponsoring organizations prioritize fundamental research, whereas others support applied research. Be sure your project fits the mission statement of the granting organization. Look at recently funded proposals and/or sample proposals on the agency website, if available. The Research or Grants Office at your institution may be able to help with finding grant opportunities.

- Make a spreadsheet of grant opportunities, with a link to the call for proposals page, the mission and aims of the agency, and the deadline for submission. Use the information that you have compiled in your spreadsheet to decide what to apply for.

- Once you have made your decision, carefully read the instructions in the call for proposals. Make a list of all the documents you need to apply, and note the formatting requirements and page limits. Know exactly what the funding agency requires of submitted proposals.

- Reach out to support staff at your university (for example, at your Research or Grants Office), potential mentors, or collaborators. For example, internal deadlines for submitting external grants are often earlier than the submission date. Make sure to learn about your institution’s internal processes, and obtain contact information for the relevant support staff.

- Applying for a grant or fellowship involves administrative work. Start preparing your CV and begin collecting supporting documents from collaborators, such as letters of support. If the application to the sponsoring agency is electronic, schedule time to set up an account, log into the system, download necessary forms and paperwork, etc. Don’t leave all of the administrative tasks until the end.

- Map out the important deadlines on your calendar. These might include video calls with collaborators, a date for the first draft to be complete, internal submission deadlines, and the funding agency deadline.

- Schedule time on your calendar for research, writing, and administrative tasks associated with the project. It’s wise to group similar tasks and block out time for them (a process known as ” time batching ”). Break down bigger tasks into smaller ones.

Now that you know what you are applying for, you can think about matching your proposed research to the aims of the agency. The work you propose needs to be innovative, specific, realizable, timely, and worthy of the sponsoring organization’s attention.

- Develop an awareness of the important problems and open questions in your field. Attend conferences and seminar talks and follow all of your field’s major journals.

- Read widely and deeply. Journal review articles are a helpful place to start. Reading papers from related but different subfields can generate ideas. Taking detailed notes as you read will help you recall the important findings and connect disparate concepts.

- Writing a grant proposal is a creative and imaginative endeavor. Write down all of your ideas. Freewriting is a practice where you write down all that comes to mind without filtering your ideas for feasibility or stopping to edit mistakes. By continuously writing your thoughts without judgment, the practice can help overcome procrastination and writer’s block. It can also unleash your creativity, and generate new ideas and associations. Mind mapping is another technique for brainstorming and generating connections between ideas.

- Establish a regular writing practice. Schedule time just for writing, and turn off all distractions during your focused work time. You can use your writing process to refine your thoughts and ideas.

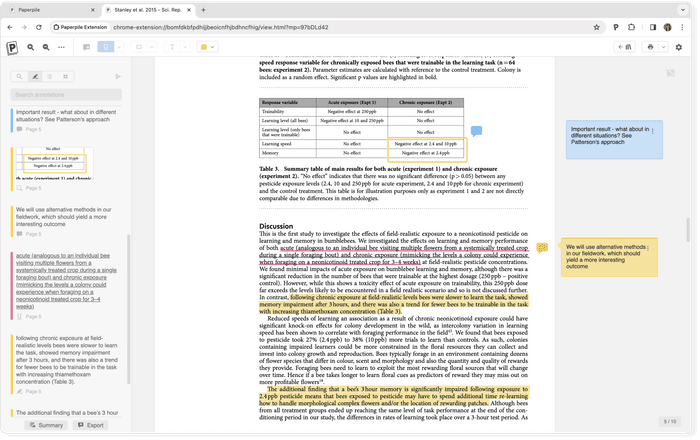

- Use a reference manager to build a library of sources for your project. You can use a reference management tool to collect papers , store and organize references , and highlight and annotate PDFs . Establish a system for organizing your ideas by tagging papers with labels and using folders to store similar references.

To facilitate intelligent thinking and shape the overall direction of your project, try answering the following questions:

- What are the questions that the project will address? Am I excited and curious about their answers?

- Why are these questions important?

- What are the goals of the project? Are they SMART (Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant, and Timely)?

- What is novel about my project? What is the gap in current knowledge?

- What methods will I use, and how feasible is my approach?

- Can the work be done over the proposed period, and with the budget I am requesting?

- Do I have relevant experience? For example, have I completed similar work funded by previous grants or written papers on my proposed topic?

- What pilot research or prior work can I use, or do I need to complete preliminary research before writing the proposal?

- Will the outcomes of my work be consequential? Will the granting agency be interested in the results?

- What solutions to open problems in my field will this project offer? Are there broader implications of my work?

- Who will the project involve? Do I need mentors, collaborators, or students to contribute to the proposed work? If so, what roles will they have?

- Who will read the proposal? For example, experts in the field will require details of methods, statistical analyses, etc., whereas non-experts may be more concerned with the big picture.

- What do I want the reviewers to feel, and take away from reading my proposal?

- What weaknesses does my proposed research have? What objections might reviewers raise, and how can I address them?

- Can I visualize a timeline for my project?

Create an actionable plan for your research project using the answers to these questions.

- Now is the time to collect preliminary data, conduct experiments, or do a preliminary study to motivate your research, and demonstrate that your proposed project is realistic.

- Use your plan to write a detailed outline of the proposal. An outline helps you to write a proposal that has a logical format and ensures your thought process is rational. It also provides a structure to support your writing.

- Follow the granting agency’s guidelines for titles, sections, and subsections to inform your outline.

At this stage, you should have identified the aims of your project, what questions your work will answer, and how they are relevant to the sponsoring agency’s call for proposals. Be able to explain the originality, importance, and achievability of your proposed work.

Now that you have done your research, you are ready to begin writing your proposal and start filling in the details of your outline. Build on the writing routine you have already started. Here are some tips:

- Follow the guidelines of the funding organization.

- Keep the proposal reviewers in mind as you write. Your audience may be a combination of specialists in your field and non-specialists. Make sure to address the novelty of your work, its significance, and its feasibility.

- Write clearly, concisely, and avoid repetition. Use topic sentences for each paragraph to emphasize key ideas. Concluding sentences of each paragraph should develop, clarify, or summarize the support for the declaration in the topic sentence. To make your writing engaging, vary sentence length.

- Avoid jargon, where possible. Follow sentences that have complex technical information with a summary in plain language.

- Don’t review all information on the topic, but include enough background information to convince reviewers that you are knowledgeable about it. Include preliminary data to convince reviewers you can do the work. Cite all relevant work.

- Make sure not to be overly ambitious. Don’t propose to do so much that reviewers doubt your ability to complete the project. Rather, a project with clear, narrowly-defined goals may prove favorable to reviewers.

- Accurately represent the scope of your project; don’t exaggerate its impacts. Avoid bias. Be forthright about the limitations of your research.

- Ensure to address potential objections and concerns that reviewers may have with the proposed work. Show that you have carefully thought about the project by explaining your rationale.

- Use diagrams and figures effectively. Make sure they are not too small or contain too much information or details.

After writing your first draft, read it carefully to gain an overview of the logic of your argument. Answer the following questions:

- Is your proposal concise, explicit, and specific?

- Have you included all necessary assumptions, data points, and evidence in your proposal?

- Do you need to make structural changes like moving or deleting paragraphs or including additional tables or figures to strengthen your rationale?

- Have you answered most of the questions posed in Step 2 above in your proposal?

- Follow the length requirements in the proposal guidelines. Don't feel compelled to include everything you know!

- Use formatting techniques to make your proposal easy on the eye. Follow rules for font, layout, margins, citation styles , etc. Avoid walls of text. Use bolding and italicizing to emphasize points.

- Comply with all style, organization, and reference list guidelines to make it easy to reviewers to quickly understand your argument. If you don’t, it’s at best a chore for the reviewers to read because it doesn’t make the most convincing case for you and your work. At worst, your proposal may be rejected by the sponsoring agency without review.

- Using a reference management tool like Paperpile will make citation creation and formatting in your grant proposal quick, easy and accurate.

Now take time away from your proposal, for at least a week or more. Ask trusted mentors or collaborators to read it, and give them adequate time to give critical feedback.

- At this stage, you can return to any remaining administrative work while you wait for feedback on the proposal, such as finalizing your budget or updating your CV.

- Revise the proposal based on the feedback you receive.

- Don’t be discouraged by critiques of your proposal or take them personally. Receiving and incorporating feedback with humility is essential to grow as a grant writer.

Now you are almost ready to submit. This is exciting! At this stage, you need to block out time to complete all final checks.

- Allow time for proofreading and final editing. Spelling and grammar mistakes can raise questions regarding the rigor of your research and leave a poor impression of your proposal on reviewers. Ensure that a unified narrative is threaded throughout all documents in the application.

- Finalize your documents by following a checklist. Make sure all documents are in place in the application, and all formatting and organizational requirements are met.

- Follow all internal and external procedures. Have login information for granting agency and institution portals to hand. Double-check any internal procedures required by your institution (applications for large grants often have a deadline for sign-off by your institution’s Research or Grants Office that is earlier than the funding agency deadline).

- To avoid technical issues with electronic portals, submit your proposal as early as you can.

- Breathe a sigh of relief when all the work is done, and take time to celebrate submitting the proposal! This is already a big achievement.

Now you wait! If the news is positive, congratulations!

But if your proposal is rejected, take heart in the fact that the process of writing it has been useful for your professional growth, and for developing your ideas.

Bear in mind that because grants are often highly competitive, acceptance rates for proposals are usually low. It is very typical to not be successful on the first try and to have to apply for the same grant multiple times.

Here are some tips to increase your chances of success on your next attempt:

- Remember that grant writing is often not a linear process. It is typical to have to use the reviews to revise and resubmit your proposal.

- Carefully read the reviews and incorporate the feedback into the next iteration of your proposal. Use the feedback to improve and refine your ideas.

- Don’t ignore the comments received from reviewers—be sure to address their objections in your next proposal. You may decide to include a section with a response to the reviewers, to show the sponsoring agency that you have carefully considered their comments.

- If you did not receive reviewer feedback, you can usually request it.

You learn about your field and grow intellectually from writing a proposal. The process of researching, writing, and revising a proposal refines your ideas and may create new directions for future projects. Professional opportunities exist for researchers who are willing to persevere with submitting grant applications.

➡️ Secrets to writing a winning grant

➡️ How to gain a competitive edge in grant writing

➡️ Ten simple rules for writing a postdoctoral fellowship

A grant proposal should include all the documents listed as required by the sponsoring organization. Check what documents the granting agency needs before you start writing the proposal.

Granting agencies have strict formatting requirements, with strict page limits and/or word counts. Check the maximum length required by the granting agency. It is okay for the proposal to be shorter than the maximum length.

Expect to spend many hours, even weeks, researching and writing a grant proposal. Consequently, it is important to start early! Block time in your calendar for research, writing, and administration tasks. Allow extra time at the end of the grant-writing process to edit, proofread, and meet presentation guidelines.

The most important part of a grant proposal is the description of the project. Make sure that the research you propose in your project narrative is new, important, and viable, and that it meets the goals of the sponsoring organization.

A grant proposal typically consists of a set of documents. Funding agencies have specific requirements for the formatting and organization of each document. Make sure to follow their guidelines exactly.

IMAGES