psychologyrocks

Gender and obedience.

In Milgram’s original study he only used male participants and some have suggested that this was appropriate as many of the death camp officers, whose behaviour he wished to explore, would have been male, however not all of them were male. The Reader is a great film/book about a female officer for example. To this end Milgram’s study has been called androcentric , in that it possible that his findings would not explain the behaviour of female participants.

It could be argued that Milgram’s work shows beta-bias, meaning that he erroneously minimises the role of potential differences between males and females, for example, assuming that there was no need to test females as the results would have been very similar. Eventually, he decided to test female participants as he realised that maybe women may behave differently. It is worth remembering that when researchers expect gender differences it is possible that they will perceive differences that are perhaps rather minimal, and these differences will become over-exaggerated this is known as alpha bias. In Milgram;s experiment 8 however, Milgram’s findings were exactly the same as the initial study in 1963. Females also showed an obedience rate of 65% just like the males. However, there were some differences in the qualitative data, i.e. what Milgram observed and noted about how they interacted with the experimenter and the learner . He also found some differences in the rates of tension that he recorded in the post-study questionnaires. You can read more about his findings in his book “Obedience to Authority” Experiment 8 where he talks a lot about one particular Pp Elinor Rosenblum.

Milgram noticed that his females Pps seemed more agitated by what they were doing and experienced higher levels of tension, he perceived that they felt more empathy for the learner which increased their levels of anxiety and that they found it harder to defy the male experimenter, due to their gender. However, these are Milgram’s perceptions as a male researcher. Maybe, he is displaying alpha bias here, maybe he is seeing gender differences where there are none. It may also not be right to assume that males do not feel as much empathy for the learner simply because they do not show it as readily in their observable behaviour.

During our lessons on this topic, we will also discuss the work of Carol Gilligan which was first discussed in her seminal book, “In a different voice” where she says that men and women may base their moral decision-making on differing perspectives. She conducted thematic analysis on the transcripts of interviews, where male and females Pps were asked to talk about various moral dilemmas. She spotted emergent themes relating to two differing perspectives known as the ethic of justice (more commonly used by males) and the ethic of care (more commonly used by females). You can read more about this on this website which talks about another famous theory in psychology which is criticised for being androcentric, Lawrence Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Reasoning . You should ensure that you have detailed notes n this as it will be useful in the issues and debates topic.

Gilligan argues that moral reasoning based on the ethic of care is NOT inferior but different and dependent upon our socialisation experiences. Males and females are exposed to different experiences due to gender stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination in society, which shape the way people think, feel and behave dependent on, amongst other social categories, our gender. She therefore believes that the differences seen in the Milgram study between males and females may be due to differing perspectives regarding the morality of the situation.

This PowerPoint talks through the results of a number of studies on gender and obedience: gender-and-obedience

A sheet of images to chop up and stick into books as a centre piece for notes on ethic of justice and ethic of care, pair work discussions on hypotheses etc: gender obedience images

This link contains more interesting information about the Sheridan and King study: http://www.madsciencemuseum.com/msm/pl/shock_puppy

This google book gives more detail about the Kilham and Mann study which may be necessary when evaluating the study: More detail on Kilham and Mann

This article discusses the work of Gilligan and Kohlberg: How might gender affect obedience; Carol Gilligan’s views on the ethic of care versus the ethic of justice

This review article by Blass also looks at various factors affecting obedience including gender: blass1999-replciations-of-milgram-and-gender-diffs-2

This is a quiz to assess your recall of the gender studies: gender-quick-test

This is a worksheet to fill in to assess your recall of Gilligan’s take on moral reasoning: how-does-gender-affect-obedience

Word-mint crossword: Gender_and_Obedience

Wordmint Bingo: Gender and Obedience – WordMint

Your assessment task:

- Write a diary entry as though you were a participant in the Milgram study. You may choose whether you wish to write as a male or a female. This does not need to match your own gender. In your writing you need to reflect values relating to the ethic of justice or the ethic of care dependent on the gender you have chosen. (4)

You may like to use the following sheet to help plan your answer: gender-gilligan-hw

Once you have completed this HW; feel free to collect the password form me so you can check out some possible answers

Practice Questions

2. Describe the influence of gender on obedience (2)

3. To what extent does gender appear to affect obedience? (8)

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Stanley Milgram Shock Experiment

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University, carried out one of the most famous studies of obedience in psychology.

He conducted an experiment focusing on the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience.

Milgram (1963) examined justifications for acts of genocide offered by those accused at the World War II, Nuremberg War Criminal trials. Their defense often was based on obedience – that they were just following orders from their superiors.

The experiments began in July 1961, a year after the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Milgram devised the experiment to answer the question:

Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” (Milgram, 1974).

Milgram (1963) wanted to investigate whether Germans were particularly obedient to authority figures, as this was a common explanation for the Nazi killings in World War II.

Milgram’s Experiment (1963)

The study was designed to measure how far participants would go in obeying an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience.

Specifically, it aimed to quantify the level of shock participants were willing to administer to another person under the guise of a learning experiment when instructed to do so by an authority figure.

Milgram also investigated the conditions under which people obey or disobey authority and the psychological mechanisms (reasons) behind obedience and disobedience.

- Size : The study involved 40 male participants aged between 20 and 50 years.

- Method : Participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements and direct mail solicitation. All subjects believed they were voluntarily participating in a study on memory and learning at Yale University. This method is known as volunteer or self-selecting sampling.

- Demographics: Participants were drawn from New Haven and surrounding communities. The sample included a wide range of occupations, including postal clerks, high school teachers, salesmen, engineers, and laborers. Participants ranged in educational level from those who had not finished elementary school to those with doctorate and other professional degrees.

- Compensation : Participants were paid $4.50 for their participation in the experiment. However, they were told that the payment was simply for coming to the laboratory, regardless of what happened after they arrived.

The procedure involved pairing participants with a confederate (Mr. Wallace), assigning roles through a rigged draw, and setting up a scenario where the participant (always the teacher) was instructed to administer electric shocks to the confederate (learner) for incorrect answers to a memory task.

- The participant and the confederate drew slips from a hat to determine their roles.

- The drawing was rigged so that both slips contained the word “Teacher.”

- The ‘true’ participant was always first to choose.

- This ensured that the naive subject (real participant) was always assigned the role of teacher, while the confederate was always the learner.

Before ‘drawing lots’ to decide who became the teacher and who became the learner Milgram told the participants about the effects of punishment on learning:

We know very little about the effects of punishment on learning. This is because almost no scientific studies have been conducted (on human beings). We don’t know how much punishment is best for learning/whether it is beneficial to learning; We also don’t know how much difference it makes as to who is giving the punishment: So in this study, we are bringing together people from different occupations (to test this out); We want to know what effect different people have on each other as teachers and learners.

The learner (Mr. Wallace) was taken into a room and strapped into an electric chair apparatus.

The teacher (real participant) and experimenter (a confederate called Mr. William) went into a separate room next door that contained an electric shock generator.

The ‘Learning Task’

The teacher real participant) was given a preliminary series of 10 words to read to the learner (confederate), with 7 predetermined wrong answers, reaching 105 volts.

After the practice round, a second list was given, and the teacher was told to repeat the procedure until all word pairs were learned correctly.

The participant (teacher) read a second list of word pairs to the learner. The participant then read one word from each pair and provided four possible options for the matching word.

The learner had to indicate which word had been originally paired with the first word by pressing one of four switches.

This task served as the pretext for administering shocks, allowing the experimenters to study obedience to authority in a controlled setting.

Each incorrect answer resulted in a shock, while a correct answer moved the process to the next word.

Fake Shock Generator

The shocks in Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments were not real. The “learners” were actors who were part of the experiment and did not actually receive any shocks.

However, the “teachers” (the real participants of the study) believed the shocks were real, which was crucial for the experiment to measure obedience to authority figures even when it involved causing harm to others.

The participant was given a mild electric shock of 45v to the wrist to convince them that the shocks were genuine. Milgram watched through a one-way mirror.

- The device consisted of 30 lever switches or bttons.

- Each switch was clearly labeled with a voltage level.

- The voltage range spanned from 15 volts to 450 volts.

- The voltage increased by 15-volt increments between each switch.

- When a switch was pressed, a red light would illuminate, an electric buzzing sound was emitted, and a blue light labeled “voltage energizer” would light up.

- The voltage levels were labeled from “Slight Shock” to “XXX”.

Learner (confederate)

The learner (Mr. Wallace) was a confederate (stooge) who pretended to be a real participant. He was 47 years old, mild-minded, Irish-American, and was an accountant in real life.

The learner was taken into a separate room and strapped into an electric chair apparatus. He had electrodes attached to his wrist with paste (to avoid blistering). The experimenter explained that the straps were to prevent excessive movement.

The learner’s responses were predetermined, with a schedule of approximately three wrong answers to one correct answer. This standardized protocal was used for all 40 participants.

The learner continued to provide answers (mostly incorrect) up until the 300v shock, and makes noises of pain when he receives a shock.

When the 300v shock is administered, the learner pounds on the room’s wall, which is heard by the participant.

The learner stops responding to the questions after receiving the 300v shock.

After getting the 315v shock, the pounding is repeated and afterward, no response appears for the questions, and he is not heard from.

Experimenter (confederate authority figure)

There was also an “experimenter” dressed in a gray lab coat, played by an actor (a 31-year-old male school biology teacher in a coat called ‘Mr. William’. He wore a grey technician coat and had a stern manner).

The experimenter (Mr. Williams) instructs the teacher (real participant) to administer an electric shock each time the learner makes a mistake, increasing the shock level by 15 volts with each error.

He advises the participants to allow 5-10 seconds before considering no response as a wrong answer, and to increase the shock level one step each time the learner fails to respond correctly. The participant gave the shock by pressing a button on the shock generator.

Additionally, the experimenter tells the teacher to announce the voltage level before administering each shock.

When the teacher refused to administer a shock, the experimenter (Mr. Williams) instructed a series of standardized orders/prods to ensure they continued.

There were four standardized, scripted prods, and if one was not obeyed, then the experimenter (Mr. Williams) read out the next prod, and so on.

If a prod was unsuccessful or the participant insisted on stopping, the experimenter moved on to the next one, and so on.

The tone was firm but not impolite. The prods were repeated if the participant showed reluctance to continue.

- Prod 1 : Please continue / please go on.

- Prod 2: The experiment requires you to continue.

- Prod 3 : It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- Prod 4 : You have no other choice but to continue.

These prods were to be used in order, and begun afresh for each new attempt at defiance (Milgram, 1974, p. 21).

If the final prod was unsuccessful or the participant stopped reading words, the study ended.

There were special prods if physical injury was asked about;

- Although the shocks may be painful, there is no permanent tissue damage, so please go on.

- Whether the learner likes it or not, you must go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly. So please go on.

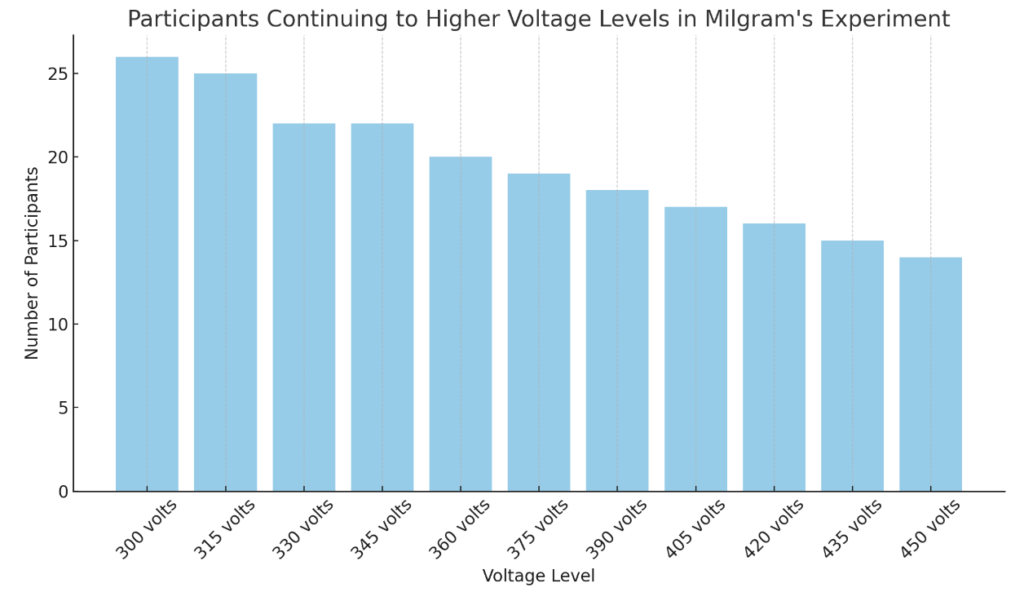

- 65% (two-thirds) of participants (i.e., teachers) continued to the highest level of 450 volts. All the participants continued to 300 volts.

- 14 defiant participants stopped early: 5 stopped at 300v, 4 at 315v, 2 at 330v, and 1 each at 345v, 360v, and 375v.

- Milgram did more than one experiment – he carried out 18 variations of his study. All he did was alter the situation (IV) to see how this affected obedience (DV).

Additional results:

- Participants often showed signs of extreme tension, including sweating, biting their lips, trembling, stuttering, digging nails into their flesh, and nervous laughter.

- Some participants exhibited full-blown, uncontrollable seizures of laughter.

- In the post-experimental interview, subjects rated the pain of the last few shocks on a 14-point scale. The modal response was 14 (Extremely painful) with a mean of 13.42.

Conclusion

- People appear to be more obedient to authority figures than we might expect. Ordinary individuals are likely to follow orders given by an authority figure, even to the extent of potentially causing harm to an innocent human being.

- When people are given orders to act destructively they will experience high levels of stress and anxiety.

- People are willing to harm someone if responsibility is taken away and passed on to someone else.

Situational factors affected obedience:

The individual explanation for the behavior of the participants would be that it was something about them as people that caused them to obey, but a more realistic explanation is that the situation they were in influenced them and caused them to behave in the way that they did.

Some aspects of the situation that may have influenced their behavior include the formality of the location, the behavior of the experimenter, and the fact that it was an experiment for which they had volunteered and been paid.

- Institutional authority : The experiment’s association with Yale University lent it significant credibility and legitimacy.

- Authoritative uniform: The experimenter wore a gray technician’s lab coat portraying authority and scientific status.

- Buffers from the consequences: The physical separation from the learner reduced the emotional impact of the participants’ actions.

- Divided responsibility : The presence of the experimenter allowed participants to feel they were not solely responsible for their actions.

- Gradual nature of the task : The incremental increase in shock intensity made it harder for participants to determine a clear point to refuse.

- Limited time for reflection : The rapid progression of events gave participants little opportunity to carefully consider their actions.

- Contractual obligation : Having agreed to participate, subjects felt a commitment to see the experiment through.

People tend to obey orders from other people if they recognize their authority as morally right and/or legally based. This response to legitimate authority is learned in a variety of situations, for example in the family, school, and workplace.

Milgram summed up in the article “The Perils of Obedience” (Milgram 1974), writing:

“The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous import, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects’ [participants’] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects’ [participants’] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.”

Milgram’s Agency Theory

Milgram (1974) explained the behavior of his participants by suggesting that people have two states of behavior when they are in a social situation:

- The autonomous state – people direct their own actions, and they take responsibility for the results of those actions.

- The agentic state – people allow others to direct their actions and then pass off the responsibility for the consequences to the person giving the orders. In other words, they act as agents for another person’s will.

Milgram suggested that two things must be in place for a person to enter the agentic state:

- The person giving the orders is perceived as being qualified to direct other people’s behavior. That is, they are seen as legitimate.

- The person being ordered about is able to believe that the authority will accept responsibility for what happens.

According to Milgram, when in this agentic state, the participant in the obedience studies “defines himself in a social situation in a manner that renders him open to regulation by a person of higher status. In this condition the individual no longer views himself as responsible for his own actions but defines himself as an instrument for carrying out the wishes of others” (Milgram, 1974, p. 134).

Agency theory says that people will obey an authority when they believe that the authority will take responsibility for the consequences of their actions. This is supported by some aspects of Milgram’s evidence.

For example, when participants were reminded that they had responsibility for their own actions, almost none of them were prepared to obey.

In contrast, many participants who were refusing to go on did so if the experimenter said that he would take responsibility.

According to Milgram (1974, p. 188):

“The behavior revealed in the experiments reported here is normal human behavior but revealed under conditions that show with particular clarity the danger to human survival inherent in our make-up.

And what is it we have seen? Not aggression, for there is no anger, vindictiveness, or hatred in those who shocked the victim….

Something far more dangerous is revealed: the capacity for man to abandon his humanity, indeed, the inevitability that he does so, as he merges his unique personality into larger institutional structures.”

Milgram Experiment Variations

The Milgram experiment was carried out many times whereby Milgram (1965) varied the basic procedure (changed the IV). By doing this Milgram could identify which factors affected obedience (the DV).

Obedience was measured by how many participants shocked to the maximum 450 volts (65% in the original study). Stanley Milgram conducted a total of 23 variations (also called conditions or experiments) of his original obedience study:

In total, 636 participants were tested in 18 variation studies conducted between 1961 and 1962 at Yale University.

In the original baseline study – the experimenter wore a gray lab coat to symbolize his authority (a kind of uniform).

The lab coat worn by the experimenter in the original study served as a crucial symbol of scientific authority that increased obedience. The lab coat conveyed expertise and legitimacy, making participants see the experimenter as more credible and trustworthy.

Milgram carried out a variation in which the experimenter was called away because of a phone call right at the start of the procedure.

The role of the experimenter was then taken over by an ‘ordinary member of the public’ ( a confederate) in everyday clothes rather than a lab coat. The obedience level dropped to 20%.

Change of Location: The Mountain View Facility Study (1963, unpublished)

Milgram conducted this variation in a set of offices in a rundown building, claiming it was associated with “Research Associates of Bridgeport” rather than Yale.

The lab’s ordinary appearance was designed to test if Yale’s prestige encouraged obedience. Participants were led to believe that a private research firm experimented.

In this non-university setting, obedience rates dropped to 47.5% compared to 65% in the original Yale experiments. This suggests that the status of location affects obedience.

Private research firms are viewed as less prestigious than certain universities, which affects behavior. It is easier under these conditions to abandon the belief in the experimenter’s essential decency.

The impressive university setting reinforced the experimenter’s authority and conveyed an implicit approval of the research.

Milgram filmed this variation for his documentary Obedience , but did not publish the results in his academic papers. The study only came to wider light when archival materials, including his notes, films, and data, were studied by later researchers like Perry (2013) in the decades after Milgram’s death.

Two Teacher Condition

When participants could instruct an assistant (confederate) to press the switches, 92.5% shocked to the maximum of 450 volts.

Allowing the participant to instruct an assistant to press the shock switches diffused personal responsibility and likely reduced perceptions of causing direct harm.

By attributing the actions to the assistant rather than themselves, participants could more easily justify shocking to the maximum 450 volts, reflected in the 92.5% obedience rate.

When there is less personal responsibility, obedience increases. This relates to Milgram’s Agency Theory.

Touch Proximity Condition

The teacher had to force the learner’s hand down onto a shock plate when the learner refused to participate after 150 volts. Obedience fell to 30%.

Forcing the learner’s hand onto the shock plate after 150 volts physically connected the teacher to the consequences of their actions. This direct tactile feedback increased the teacher’s personal responsibility.

No longer shielded from the learner’s reactions, the proximity enabled participants to more clearly perceive the harm they were causing, reducing obedience to 30%. Physical distance and indirect actions in the original setup made it easier to rationalize obeying the experimenter.

The participant is no longer buffered/protected from seeing the consequences of their actions.

Social Support Condition

When the two confederates set an example of defiance by refusing to continue the shocks, especially early on at 150 volts, it permitted the real participant also to resist authority.

Two other participants (confederates) were also teachers but refused to obey. Confederate 1 stopped at 150 volts, and Confederate 2 stopped at 210 volts.

Their disobedience provided social proof that it was acceptable to disobey. This modeling of defiance lowered obedience to only 10% compared to 65% without such social support. It demonstrated that social modeling can validate challenging authority.

The presence of others who are seen to disobey the authority figure reduces the level of obedience to 10%.

Absent Experimenter Condition

It is easier to resist the orders from an authority figure if they are not close by. When the experimenter instructed and prompted the teacher by telephone from another room, obedience fell to 20.5%.

Many participants cheated and missed out on shocks or gave less voltage than ordered by the experimenter. The proximity of authority figures affects obedience.

The physical absence of the authority figure enabled participants to act more freely on their own moral inclinations rather than the experimenter’s commands. This highlighted the role of an authority’s direct presence in influencing behavior.

A key reason the obedience studies fascinate people is Milgram presented them as a scientific experiment, contrasting himself as an “empirically grounded scientist” compared to philosophers. He claimed he systematically varied factors to alter obedience rates.

However, recent scholarship using archival records shows Milgram’s account of standardizing the procedure was misleading. For example, he published a list of standardized prods the experimenter used when participants questioned continuing. Milgram said these were delivered uniformly in a firm but polite tone.

Analyzing audiotapes, Gibson (2013) found considerable variation from the published protocol – the prods differed across trials. The point is not that Milgram did poor science, but that the archival materials reveal the limitations of the textbook account of his “standardized” procedure.

The qualitative data like participant feedback, Milgram’s notes, and researchers’ actions provide a fuller, messier picture than the obedience studies’ “official” story. For psychology students, this shows how scientific reporting can polish findings in a way that strays from the less tidy reality.

Critical Evaluation

Inaccurate description of the prod methodology:.

A key reason obedience studies fascinate people is Milgram (1974) presented them as a scientific experiment, contrasting himself as an “empirically grounded scientist” compared to philosophers. He claimed he systematically varied factors to alter obedience rates.

However, recent scholarship using archival records shows Milgram’s account of standardizing the procedure was misleading. For example, he published a list of standardized prods the experimenter used when participants questioned continuing. Milgram said these were delivered uniformly in a firm but polite tone (Gibson, 2013; Perry, 2013; Russell, 2010).

Perry’s (2013) archival research revealed another discrepancy between Milgram’s published account and the actual events. Milgram claimed standardized prods were used when participants resisted, but Perry’s audiotape analysis showed the experimenter often improvised more coercive prods beyond the supposed script.

This off-script prodding varied between experiments and participants, and was especially prevalent with female participants where no gender obedience difference was found – suggesting the improvisation influenced results. Gibson (2013) and Russell (2009) corroborated the experimenter’s departures from the supposed fixed prods.

Prods were often combined or modified rather than used verbatim as published.

Russell speculated the improvisation aimed to achieve outcomes the experimenter believed Milgram wanted. Milgram seemed to tacitly approve of the deviations by not correcting them when observing.

This raises significant issues around experimenter bias influencing results, lack of standardization compromising validity, and ethical problems with Milgram misrepresenting procedures.

Milgram’s experiment lacked external validity:

The Milgram studies were conducted in laboratory-type conditions, and we must ask if this tells us much about real-life situations.

We obey in a variety of real-life situations that are far more subtle than instructions to give people electric shocks, and it would be interesting to see what factors operate in everyday obedience. The sort of situation Milgram investigated would be more suited to a military context.

Orne and Holland (1968) accused Milgram’s study of lacking ‘experimental realism,”’ i.e.,” participants might not have believed the experimental set-up they found themselves in and knew the learner wasn’t receiving electric shocks.

“It’s more truthful to say that only half of the people who undertook the experiment fully believed it was real, and of those two-thirds disobeyed the experimenter,” observes Perry (p. 139).

Milgram’s sample was biased:

- The participants in Milgram’s study were all male. Do the findings transfer to females?

- Milgram’s study cannot be seen as representative of the American population as his sample was self-selected. This is because they became participants only by electing to respond to a newspaper advertisement (selecting themselves).

- They may also have a typical “volunteer personality” – not all the newspaper readers responded so perhaps it takes this personality type to do so.

Yet a total of 636 participants were tested in 18 separate experiments across the New Haven area, which was seen as being reasonably representative of a typical American town.

Milgram’s findings have been replicated in a variety of cultures and most lead to the same conclusions as Milgram’s original study and in some cases see higher obedience rates.

However, Smith and Bond (1998) point out that with the exception of Jordan (Shanab & Yahya, 1978), the majority of these studies have been conducted in industrialized Western cultures, and we should be cautious before we conclude that a universal trait of social behavior has been identified.

Selective reporting of experimental findings:

Perry (2013) found Milgram omitted findings from some obedience experiments he conducted, reporting only results supporting his conclusions. A key omission was the Relationship condition (conducted in 1962 but unpublished), where participant pairs were relatives or close acquaintances.

When the learner protested being shocked, most teachers disobeyed, contradicting Milgram’s emphasis on obedience to authority.

Perry argued Milgram likely did not publish this 85% disobedience rate because it undermined his narrative and would be difficult to defend ethically since the teacher and learner knew each other closely.

Milgram’s selective reporting biased interpretations of his findings. His failure to publish all his experiments raises issues around researchers’ ethical obligation to completely and responsibly report their results, not just those fitting their expectations.

Unreported analysis of participants’ skepticism and its impact on their behavior:

Perry (2013) found archival evidence that many participants expressed doubt about the experiment’s setup, impacting their behavior. This supports Orne and Holland’s (1968) criticism that Milgram overlooked participants’ perceptions.

Incongruities like apparent danger, but an unconcerned experimenter likely cued participants that no real harm would occur. Trust in Yale’s ethics reinforced this. Yet Milgram did not publish his assistant’s analysis showing participant skepticism correlated with disobedience rates and varied by condition.

Obedient participants were more skeptical that the learner was harmed. This selective reporting biased interpretations. Additional unreported findings further challenge Milgram’s conclusions.

This highlights issues around thoroughly and responsibly reporting all results, not just those fitting expectations. It shows how archival evidence makes Milgram’s study a contentious classic with questionable methods and conclusions.

Ethical Issues

What are the potential ethical concerns associated with Milgram’s research on obedience?

While not a “contribution to psychology” in the traditional sense, Milgram’s obedience experiments sparked significant debate about the ethics of psychological research.

Baumrind (1964) criticized the ethics of Milgram’s research as participants were prevented from giving their informed consent to take part in the study.

Participants assumed the experiment was benign and expected to be treated with dignity.

As a result of studies like Milgram’s, the APA and BPS now require researchers to give participants more information before they agree to take part in a study.

The participants actually believed they were shocking a real person and were unaware the learner was a confederate of Milgram’s.

However, Milgram argued that “illusion is used when necessary in order to set the stage for the revelation of certain difficult-to-get-at-truths.”

Milgram also interviewed participants afterward to find out the effect of the deception. Apparently, 83.7% said that they were “glad to be in the experiment,” and 1.3% said that they wished they had not been involved.

Protection of participants

Participants were exposed to extremely stressful situations that may have the potential to cause psychological harm. Many of the participants were visibly distressed (Baumrind, 1964).

Signs of tension included trembling, sweating, stuttering, laughing nervously, biting lips and digging fingernails into palms of hands. Three participants had uncontrollable seizures, and many pleaded to be allowed to stop the experiment.

Milgram described a businessman reduced to a “twitching stuttering wreck” (1963, p. 377),

In his defense, Milgram argued that these effects were only short-term. Once the participants were debriefed (and could see the confederate was OK), their stress levels decreased.

“At no point,” Milgram (1964) stated, “were subjects exposed to danger and at no point did they run the risk of injurious effects resulting from participation” (p. 849).

To defend himself against criticisms about the ethics of his obedience research, Milgram cited follow-up survey data showing that 84% of participants said they were glad they had taken part in the study.

Milgram used this to claim that the study caused no serious or lasting harm, since most participants retrospectively did not regret their involvement.

Yet archival accounts show many participants endured lasting distress, even trauma, refuting Milgram’s insistence the study caused only fleeting “excitement.” By not debriefing all, Milgram misled participants about the true risks involved (Perry, 2013).

However, Milgram did debrief the participants fully after the experiment and also followed up after a period of time to ensure that they came to no harm.

Milgram debriefed all his participants straight after the experiment and disclosed the true nature of the experiment.

Participants were assured that their behavior was common, and Milgram also followed the sample up a year later and found no signs of any long-term psychological harm.

The majority of the participants (83.7%) said that they were pleased that they had participated, and 74% had learned something of personal importance.

Perry’s (2013) archival research found Milgram misrepresented debriefing – around 600 participants were not properly debriefed soon after the study, contrary to his claims. Many only learned no real shocks occurred when reading a mailed study report months later, which some may have not received.

Milgram likely misreported debriefing details to protect his credibility and enable future obedience research. This raises issues around properly informing and debriefing participants that connect to APA ethics codes developed partly in response to Milgram’s study.

Right to Withdrawal

The British Psychological Society (BPS) states that researchers should make it plain to participants that they are free to withdraw at any time (regardless of payment).

When expressing doubts, the experimenter assured them that all was well. Trusting Yale scientists, many took the experimenter at his word that “no permanent tissue damage” would occur, and continued administering shocks despite reservations.

Did Milgram give participants an opportunity to withdraw? The experimenter gave four verbal prods which mostly discouraged withdrawal from the experiment:

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

Milgram argued that they were justified as the study was about obedience, so orders were necessary.

Milgram pointed out that although the right to withdraw was made partially difficult, it was possible as 35% of participants had chosen to withdraw.

Replications

Direct replications have not been possible due to current ethical standards .

However, several researchers have conducted partial replications and variations that aim to reproduce some aspects of Milgram’s methods ethically.

One important replication was conducted by Jerry Burger in 2009. Burger’s partial replication included several safeguards to protect participant welfare, such as screening out high-risk individuals, repeatedly reminding participants they could withdraw, and stopping at the 150-volt shock level. This was the point where Milgram’s participants first heard the learner’s protests.

As 79% of Milgram’s participants who went past 150 volts continued to the maximum 450 volts, Burger (2009) argued that 150 volts provided a reasonable estimate for obedience levels. He found 70% of participants continued to 150 volts, compared to 82.5% in Milgram’s comparable condition.

Another replication by Thomas Blass (1999) examined whether obedience rates had declined over time due to greater public awareness of the experiments.

Blass correlated obedience rates from replication studies between 1963 and 1985 and found no relationship between year and obedience level. He concluded that obedience rates have not systematically changed, providing evidence against the idea of “enlightenment effects”.

Some variations have explored the role of gender. Milgram found equal rates of obedience for male and female participants. Reviews have found most replications also show no gender difference, with a couple of exceptions (Blass, 1999). For example, Kilham and Mann (1974) found lower obedience in female participants.

Partial replications have also examined situational factors. Having another person model defiance reduced obedience compared to a solo participant in one study, but did not eliminate it (Burger, 2009).

The authority figure’s perceived expertise seems to be an influential factor (Blass, 1999). Replications have supported Milgram’s observation that stepwise increases in demands promote obedience.

Personality factors have been studied as well. Traits like high empathy and desire for control correlate with some minor early hesitation, but do not greatly impact eventual obedience levels (Burger, 2009). Authoritarian tendencies may contribute to obedience (Elms, 2009).

In sum, the partial replications confirm Milgram’s degree of obedience. Though ethical constraints prevent full reproductions, the key elements of his procedure seem to consistently elicit high levels of compliance across studies, samples, and eras. The replications continue to highlight the power of situational pressures to yield obedience.

Milgram (1963) Audio Clips

Below you can also hear some of the audio clips taken from the video that was made of the experiment. Just click on the clips below.

Why was the Milgram experiment so controversial?

The Milgram experiment was controversial because it revealed people’s willingness to obey authority figures even when causing harm to others, raising ethical concerns about the psychological distress inflicted upon participants and the deception involved in the study.

Would Milgram’s experiment be allowed today?

Milgram’s experiment would likely not be allowed today in its original form, as it violates modern ethical guidelines for research involving human participants, particularly regarding informed consent, deception, and protection from psychological harm.

Did anyone refuse the Milgram experiment?

Yes, in the Milgram experiment, some participants refused to continue administering shocks, demonstrating individual variation in obedience to authority figures. In the original Milgram experiment, approximately 35% of participants refused to administer the highest shock level of 450 volts, while 65% obeyed and delivered the 450-volt shock.

How can Milgram’s study be applied to real life?

Milgram’s study can be applied to real life by demonstrating the potential for ordinary individuals to obey authority figures even when it involves causing harm, emphasizing the importance of questioning authority, ethical decision-making, and fostering critical thinking in societal contexts.

Were all participants in Milgram’s experiments male?

Yes, in the original Milgram experiment conducted in 1961, all participants were male, limiting the generalizability of the findings to women and diverse populations.

Why was the Milgram experiment unethical?

The Milgram experiment was considered unethical because participants were deceived about the true nature of the study and subjected to severe emotional distress. They believed they were causing harm to another person under the instruction of authority.

Additionally, participants were not given the right to withdraw freely and were subjected to intense pressure to continue. The psychological harm and lack of informed consent violates modern ethical guidelines for research.

Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram’s” Behavioral study of obedience.”. American Psychologist , 19 (6), 421.

Blass, T. (1999). The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: Some things we now know about obedience to authority 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 29 (5), 955-978.

Brannigan, A., Nicholson, I., & Cherry, F. (2015). Introduction to the special issue: Unplugging the Milgram machine. Theory & Psychology , 25 (5), 551-563.

Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American Psychologist, 64 , 1–11.

Elms, A. C. (2009). Obedience lite. American Psychologist, 64 (1), 32–36.

Gibson, S. (2013). Milgram’s obedience experiments: A rhetorical analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52, 290–309.

Gibson, S. (2017). Developing psychology’s archival sensibilities: Revisiting Milgram’s obedience’ experiments. Qualitative Psychology , 4 (1), 73.

Griggs, R. A., Blyler, J., & Jackson, S. L. (2020). Using research ethics as a springboard for teaching Milgram’s obedience study as a contentious classic. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology , 6 (4), 350.

Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2018). A truth that does not always speak its name: How Hollander and Turowetz’s findings confirm and extend the engaged followership analysis of harm-doing in the Milgram paradigm. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 292–300.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Birney, M. E. (2016). Questioning authority: New perspectives on Milgram’s ‘obedience’ research and its implications for intergroup relations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11 , 6–9.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., Birney, M. E., Millard, K., & McDonald, R. (2015). ‘Happy to have been of service’: The Yale archive as a window into the engaged followership of participants in Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiment. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54 , 55–83.

Kaplan, D. E. (1996). The Stanley Milgram papers: A case study on appraisal of and access to confidential data files. American Archivist, 59 , 288–297.

Kaposi, D. (2022). The second wave of critical engagement with Stanley Milgram’s ‘obedience to authority’experiments: What did we learn?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass , 16 (6), e12667.

Kilham, W., & Mann, L. (1974). Level of destructive obedience as a function of transmitter and executant roles in the Milgram obedience paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29 (5), 696–702.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience . Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67, 371-378.

Milgram, S. (1964). Issues in the study of obedience: A reply to Baumrind. American Psychologist, 19 , 848–852.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority . Human Relations, 18(1) , 57-76.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . Harpercollins.

Miller, A. G. (2009). Reflections on” Replicating Milgram”(Burger, 2009), American Psychologis t, 64 (1):20-27

Nicholson, I. (2011). “Torture at Yale”: Experimental subjects, laboratory torment and the “rehabilitation” of Milgram’s “obedience to authority”. Theory & Psychology, 21 , 737–761.

Nicholson, I. (2015). The normalization of torment: Producing and managing anguish in Milgram’s “obedience” laboratory. Theory & Psychology, 25 , 639–656.

Orne, M. T., & Holland, C. H. (1968). On the ecological validity of laboratory deceptions. International Journal of Psychiatry, 6 (4), 282-293.

Orne, M. T., & Holland, C. C. (1968). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. On the ecological validity of laboratory deceptions. International Journal of Psychiatry, 6 , 282–293.

Perry, G. (2013). Behind the shock machine: The untold story of the notorious Milgram psychology experiments . New York, NY: The New Press.

Reicher, S., Haslam, A., & Miller, A. (Eds.). (2014). Milgram at 50: Exploring the enduring relevance of psychology’s most famous studies [Special issue]. Journal of Social Issues, 70 (3), 393–602

Russell, N. (2014). Stanley Milgram’s obedience to authority “relationship condition”: Some methodological and theoretical implications. Social Sciences, 3, 194–214

Shanab, M. E., & Yahya, K. A. (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society .

Smith, P. B., & Bond, M. H. (1998). Social psychology across cultures (2nd Edition) . Prentice Hall.

Further Reading

- The power of the situation: The impact of Milgram’s obedience studies on personality and social psychology

- Seeing is believing: The role of the film Obedience in shaping perceptions of Milgram’s Obedience to Authority Experiments

- Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today?

Learning Check

Which is true regarding the Milgram obedience study?

- The aim was to see how obedient people would be in a situation where following orders would mean causing harm to another person.

- Participants were under the impression they were part of a learning and memory experiment.

- The “learners” in the study were actual participants who volunteered to be shocked as part of the experiment.

- The “learner” was an actor who was in on the experiment and never actually received any real shocks.

- Although the participant could not see the “learner”, he was able to hear him clearly through the wall

- The study was directly influenced by Milgram’s observations of obedience patterns in post-war Europe.

- The experiment was designed to understand the psychological mechanisms behind war crimes committed during World War II.

- The Milgram study was universally accepted in the psychological community, and no ethical concerns were raised about its methodology.

- When Milgram’s experiment was repeated in a rundown office building in Bridgeport, the percentage of the participants who fully complied with the commands of the experimenter remained unchanged.

- The experimenter (authority figure) delivered verbal prods to encourage the teacher to continue, such as ‘Please continue’ or ‘Please go on’.

- Over 80% of participants went on to deliver the maximum level of shock.

- Milgram sent participants questionnaires after the study to assess the effects and found that most felt no remorse or guilt, so it was ethical.

- The aftermath of the study led to stricter ethical guidelines in psychological research.

- The study emphasized the role of situational factors over personality traits in determining obedience.

Answers : Items 3, 8, 9, and 11 are the false statements.

Short Answer Questions

- Briefly explain the results of the original Milgram experiments. What did these results prove?

- List one scenario on how an authority figure can abuse obedience principles.

- List one scenario on how an individual could use these principles to defend their fellow peers.

- In a hospital, you are very likely to obey a nurse. However, if you meet her outside the hospital, for example in a shop, you are much less likely to obey. Using your knowledge of how people resist pressure to obey, explain why you are less likely to obey the nurse outside the hospital.

- Describe the shock instructions the participant (teacher) was told to follow when the victim (learner) gave an incorrect answer.

- State the lowest voltage shock that was labeled on the shock generator.

- What would likely happen if Milgram’s experiment included a condition in which the participant (teacher) had to give a high-level electric shock for the first wrong answer?

Group Activity

Gather in groups of three or four to discuss answers to the short answer questions above.

For question 2, review the different scenarios you each came up with. Then brainstorm on how these situations could be flipped.

For question 2, discuss how an authority figure could instead empower those below them in the examples your groupmates provide.

For question 3, discuss how a peer could do harm by using the obedience principles in the scenarios your groupmates provide.

Essay Topic

- What’s the most important lesson of Milgram’s Obedience Experiments? Fully explain and defend your answer.

- Milgram selectively edited his film of the obedience experiments to emphasize obedient behavior and minimize footage of disobedience. What are the ethical implications of a researcher selectively presenting findings in a way that fits their expected conclusions?

- CNS & Neurotransmission

- Brain Functioning & Aggression

- Hormones & Genes in Aggression

- Circadian Rhythms

- Infradian Rhythms

- Correlational Research

- Brain Scanning Techniques

- Twin Studies

- Spearman’s Rank

- Raine et al. (1997)

- Brendgen et al. (2005)

- McDermott (2008)

- Theories of Obedience

- Milgram’s Research

- Factors Affecting Obedience

- Asch’s Research

- Factors Affecting Conformity

- Minority Influence

- Self-Reports

- Sampling Techniques

- Quantitative Data

- Moscovici et al. (1969)

- Burger (2009)

- Haun et al. (2014)

- The Multi-Store Model of Memory

- The Working Memory Model

- Reconstructive Memory

- Experimental Methods

- Experimental Designs

- Validity & Reliability

- Levels of Measurement

- Inferential Statistics

- Wilcoxon Signed Ranks

- Case Studies

- Bartlett (1932)

- Schmolck et al. (2002)

- Sacchi et al. (2007)

- Classical Conditioning

- Operant Conditioning

- Social learning Theory

- Psychosexual Stages

- Observations

- Qualitative Data Analysis

- Case Studies: Freud

- Chi-Squared

- Watson & Rayner (1920)

- Capafóns et al. (1998)

- Bastian et al. (2011)

- Animal Research

- Dement & Kleitman (sleep and dreams)

- Hassett et al. (monkey toy preferences)

- Hölzel et al. (mindfulness and brain scans)

- Andrade (doodling)

- Baron-Cohen et al. (eyes test)

- Pozzulo et al. (line-ups)

- Bandura et al. (aggression)

- Fagen et al. (elephant learning)

- Saavedra and Silverman (button phobia)

Milgram (obedience)

- Perry et al. (personal space)

- Piliavin et al. (subway Samaritans)

Milgram, S (1963) , Behavioral Study of Obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4): 371–78

Psychology Being Investigated

This experiment aimed to investigate the psychological mechanisms of obedience, specifically how far individuals would go in obeying an authority figure, even when the orders given are against their ethical standards.

This research was influenced by the events of World War II, particularly the Holocaust, where individuals followed orders that resulted in mass harm. Milgram wanted to understand the nature of obedience and its limits, especially how ordinary people could be influenced by authority to commit acts against their moral beliefs.

Key findings of the study included that a significant majority of participants were willing to administer the highest level of shocks, showing a strong tendency to comply with authority figures despite personal moral objections. This outcome highlighted the powerful influence of authority on individual behavior and raised important questions about responsibility and autonomy in situations involving obedience to authority.

The background of Stanley Milgram’s study is rooted in the historical and social context of the early 1960s. The experiment was designed to understand the phenomenon of obedience to authority, particularly in light of the atrocities committed during World War II, such as the Holocaust. The key question that Milgram sought to explore was: How could ordinary people be compelled to carry out horrific acts simply because they were following orders from an authority figure?

This interest was partly inspired by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi official who played a significant role in the Holocaust. Eichmann’s defense during his trial was that he was merely following orders and therefore not personally responsible for his actions. This defense raised profound moral and psychological questions about the nature of obedience and personal responsibility.

Milgram’s experiment was an attempt to scientifically investigate these issues. He wanted to see if ordinary American citizens would obey authority figures to the extent of harming another person, and under what conditions this obedience would occur. The experiment was designed to isolate the effects of authority, removing other potential factors such as peer pressure or group influence.

The broader aim was to understand the conditions under which people would commit acts that conflicted with their personal conscience and moral principles. Milgram’s research was part of a larger movement in social psychology at the time that sought to understand how social contexts and situational factors influence individual behavior. The findings from this study have had a lasting impact on our understanding of social psychology, particularly in areas related to authority, conformity, and ethical decision-making.

The aim was to investigate the extent to which individuals would follow orders from an authority figure, even when these orders involved harming another person. Specifically, Milgram sought to understand the dynamics of obedience to authority and to test the hypothesis that people are inherently inclined to obey authority figures, regardless of the morality of the action required.

- How far would individuals go in obeying an authority figure when the commands involved inflicting pain on another person?

- Would ordinary people defy their own moral and ethical principles if instructed to do so by an authority figure?

Sample and sampling technique

40 male participants aged between 20 and 50 years, from various educational and occupational backgrounds. They believed they were participating in a study on learning and memory.

Voluntary sampling – Participants were recruited through newspaper ads and direct mail solicitation, offering a small payment for participation.

Research Method

Controlled observation with a single-blind procedure (participants were unaware of the true nature of the study). The setting was Yale University’s psychology laboratory.

- Conducted at Yale University, the experiment took place in a lab setting designed to look like a learning and memory test environment. Upon arrival, each participant was assigned the role of a ´teacher´. A confederate of Milgram, who was part of the research team, played the ´learner´.

- The learner was strapped to a chair in an adjacent room, with electrodes attached, supposedly for delivering shocks.

- The teacher was shown a shock generator with switches ranging from 15 volts (labelled as “slight shock”) to 450 volts (labelled as “danger: severe shock”). To convince the teacher of the shock’s authenticity, they were given a sample 45-volt shock.

Conducting the Experiment

- The teacher read out pairs of words, and the learner had to remember and repeat them.

- Each time the learner (confederate) gave a wrong answer, which was pre-arranged, the teacher was instructed to administer a shock. With each incorrect answer, the shock level was increased.

- The learner, who wasn’t actually receiving shocks, acted out scripted responses, including grunts at lower voltages and eventually screaming, pleading to stop, and feigning unconsciousness at higher voltages.

- Experimenter’s Prods – If the teacher hesitated to administer shocks, the experimenter, an authority figure, would give standard prods like “The experiment requires that you continue,” encouraging the teacher to proceed.

Data Collection

- The primary data collected was how far each participant would go up the voltage scale before refusing to continue.

- The highest shock level the participant was willing to administer was recorded.

- Manipulated Variable – The authoritative commands by the experimenter.

- Measured Variable – The highest level of shock the participant was willing to administer.

- Standardized Instructions and Setting – The experiment was conducted in a laboratory at Yale University, which provided a controlled environment. The setting was kept consistent for each participant to ensure that environmental factors did not influence the results.

- Shock Generator and Labels – The shock generator used in the experiment had switches labeled from 15 volts (slight shock) to 450 volts (danger: severe shock). The labels were designed to give the participants a clear and consistent indication of the shock’s severity.

- Scripted Learner Responses – The learner´s (confederate) responses were consistent for each session. This included responses to the word-pair test and banging on the wall at 300V and 315V.

- Prod 1 – Please continue, or Please go on.

- Prod 2 – The experiment requires that you continue.

- Prod 3 – It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- Prod 4 – You have no other choice, you must go on.

- Special prods – If the participants asked about the learner suffering permanent injury: ¨Although the shocks may be painful, there is no permanent tissue damage, so please go on.¨

- If the participant commented that the learner wanted to stop: ¨Whether the learner likes it or not, you must go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly. So please go on.¨

- Sample Shock – To convince the participants of the authenticity of the shocks, they were given a sample 45-volt shock at the beginning of the experiment. This control ensured that each participant had a uniform perception of the shocks’ realism.

The results of Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiment are illustrated in the graph above. It shows the number of participants willing to administer each increasing voltage level:

- At 300 volts, 35 out of 40 participants were still administering shocks. No participant stopped before 300 volts.

- This number gradually decreased as the voltage increased, with 26 participants continuing to the maximum level of 450 volts.

This graph strikingly demonstrates the high level of obedience to authority, with a significant proportion of participants willing to administer potentially lethal shocks when instructed by an authority figure. The drop in numbers at higher voltages indicates some resistance or hesitation, but the overall high compliance is a notable finding of the study.

The conclusion of Stanley Milgram’s obedience study was profound and somewhat unsettling. It demonstrated that a significant proportion of ordinary people are willing to obey authority figures to an extreme extent, even to the point of harming another person, when they perceive the authority to be legitimate. Key conclusions of the study include:

High Level of Obedience – A majority of the participants (65%) administered the highest shock level of 450 volts, despite expressing discomfort and moral dilemma. This indicated that people are likely to follow orders from an authority figure, even when such orders conflict with their personal conscience.

Underestimation of Obedience – The results contradicted the expectations of both the general public and the psychological community. Before the experiment, Milgram had surveyed professionals who predicted that only a very small percentage of participants would proceed to the highest shock levels.

Power of the Situational Context – The findings highlighted the influence of the situational context and the authority figure’s presence. Participants were more likely to obey when they perceived the authority figure as legitimate and responsible for the consequences.

Ethical Issues

Deception – Participants were misled about the true nature of the experiment. They believed they were administering real shocks to the learners, which was not the case. This deception was considered necessary for the experiment’s validity but raised serious ethical questions.

Psychological Harm – Participants were subjected to extreme stress and anxiety, believing they were harming another person. This caused emotional distress, which was evident in their reactions during the experiment, such as sweating, trembling, and stuttering. Even though participants were debriefed after the experiment, the immediate psychological impact was significant.

Right to Withdrawal – Although participants were technically free to leave the experiment at any time, the verbal prods used by the experimenter (“The experiment requires that you continue”) made it difficult for them to exercise this right. This situation created a coercive environment, where participants might have felt obligated to continue.

Informed Consent – The participants did not give fully informed consent because they were not accurately informed about the nature of the study. True informed consent requires that participants are fully aware of what they are consenting to, including any potential risks.

- Controlled Environment – The laboratory setting allowed Milgram to control many variables, such as the role assignments, the scripted responses of the learner, and the consistent prodding by the experimenter. This control helped ensure that the observed effects were due to the manipulation of the independent variable (authority) rather than other external factors, allowing for high internal validity.

- Standardised Procedure – The experiment followed a standardized procedure for all participants. The consistent use of the shock generator, the scripted responses of the learner, and the experimenter’s prods ensured that each participant experienced a similar situation. This standardization reduced the risk of extraneous variables influencing the results, improving the internal validity.

- Objective Measurements – The experiment relied on quantitative data, specifically the voltage levels at which participants stopped administering shocks. This objective measurement allowed for precise and standardised comparisons between participants. This facilitates statistical analysis and also improves internal validity as it eliminates bias from the results analysis.

- Gender Bias – The experiment primarily consisted of male participants, with no female participants included in the initial study. This gender bias raises questions about the generalizability of the findings to both genders. It is possible that men and women may respond differently to authority figures, and by excluding women, the study may not fully capture the breadth of human behaviour in obedience situations.

- Cultural Representation – The participants were predominantly from Western, American backgrounds. This lack of cultural diversity limits the generalizability of the findings to other cultures, as cultural factors can significantly influence attitudes toward authority and obedience. What might be considered acceptable or authoritative in one culture may differ in another.

- Demand Characteristics – Due to the unusual nature of the experiment, participants may have speculated about its true purpose. Some participants might have guessed that the shocks were not real or that the experiment was designed to test their obedience. This speculation could have led them to modify their behavior in a way they believed was expected, potentially reducing the experiment’s internal validity.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 February 2016

Modern Milgram experiment sheds light on power of authority

- Alison Abbott

Nature volume 530 , pages 394–395 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

2 Citations

397 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

People obeying commands feel less responsibility for their actions.

More than 50 years after a controversial psychologist shocked the world with studies that revealed people’s willingness to harm others on order, a team of cognitive scientists has carried out an updated version of the iconic ‘Milgram experiments’.

Their findings may offer some explanation for Stanley Milgram's uncomfortable revelations: when following commands, they say, people genuinely feel less responsibility for their actions — whether they are told to do something evil or benign.

“If others can replicate this, then it is giving us a big message,” says neuroethicist Walter Sinnot-Armstrong of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the work. “It may be the beginning of an insight into why people can harm others if coerced: they don’t see it as their own action.”

The study may feed into a long-running legal debate about the balance of personal responsibility between someone acting under instruction and their instructor, says Patrick Haggard, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, who led the work, published on 18 February in Current Biology 1 .

Milgram’s original experiments were motivated by the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, who famously argued that he was ‘just following orders’ when he sent Jews to their deaths. The new findings don’t legitimize harmful actions, Haggard emphasizes, but they do suggest that the ‘only obeying orders’ excuse betrays a deeper truth about how a person feels when acting under command.

Ordered to shock

In a series of experiments at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in the 1960s, Milgram told his participants that a man was being trained to learn word pairs in a neighbouring room. The participants had to press a button to deliver an electric shock of escalating strength to the learner when he made an error; when they did so, they heard his cries of pain. In reality, the learner was an actor, and no shock was ever delivered. Milgram’s aim was to see how far people would go when they were ordered to step up the voltage.

Routinely, an alarming two-thirds of participants continued to step up shocks, even after the learner was apparently rendered unconscious. But Milgram did not assess his participants’ subjective feelings as they were coerced into doing something unpleasant. And his experiments have been criticized for the deception that they involved — not just because participants may have been traumatized, but also because some may have guessed that the pain wasn’t real.

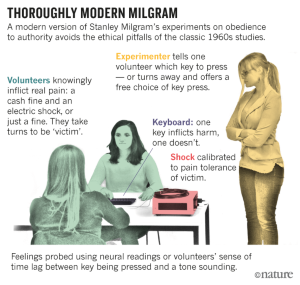

Modern teams have conducted partial and less ethically complicated replications of Milgram’s work. But Haggard and his colleagues wanted to find out what participants were feeling. They designed a study in which volunteers knowingly inflicted real pain on each other, and were completely aware of the experiment’s aims.

Because Milgram’s experiments were so controversial, Haggard says that he took “quite a deep breath before deciding to do the study”. But he says that the question of who bears personal responsibility is so important to the rule of law that he thought it was “worth trying to do some good experiments to get to the heart of the matter.”

Sense of agency

In his experiments, the volunteers (all were female, as were the experimenters, to avoid gender effects) were given £20 (US$29). In pairs, they sat facing each other across a table, with a keyboard between them. A participant designated the ‘agent’ could press one of two keys; one did nothing. But for some pairs, the other key would transfer 5p to the agent from the other participant, designated the ‘victim’; for others, the key would also deliver a painful but bearable electric shock to the victim’s arm. (Because people have different tolerances to pain, the level of the electric shock was determined for each individual before the experiment began.) In one experiment, an experimenter stood next to the agent and told her which key to press. In another, the experimenter looked away and gave the agent a free choice about which key to press.

To examine the participants’ ‘sense of agency’ — the unconscious feeling that they were in control of their own actions — Haggard and his colleagues designed the experiment so that pressing either key caused a tone to sound after a few hundred milliseconds, and both volunteers were asked to judge the length of this interval. Psychologists have established that people perceive the interval between an action and its outcome as shorter when they carry out an intentional action of their own free will, such as moving their arm, than when the action is passive, such as having their arm moved by someone else.

When they were ordered to press a key, the participants seemed to judge their action as more passive than when they had free choice — they perceived the time to the tone as longer.

In a separate experiment, volunteers followed similar protocols while electrodes on their heads recorded their neural activity through EEG (electroencephalography). When ordered to press a key, their EEG recordings were quieter — suggesting, says Haggard, that their brains were not processing the outcome of their action. Some participants later reported feeling reduced responsibility for their action.

Unexpectedly, giving the order to press the key was enough to cause the effects, even when the keystroke led to no physical or financial harm. “It seems like your sense of responsibility is reduced whenever someone orders you to do something — whatever it is they are telling you to do,” says Haggard.

The study might inform legal debate, but it also has wider relevance to other domains of society, says Sinnot-Armstrong. For example, companies that want to create — or avoid — a feeling of personal responsibility among their employees could take its lessons on board.

Caspar, E. A., Christensen, J. F., Cleeremans, A. & Haggard, P. Curr. Biol. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.067 (2016).

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

Tweet Facebook LinkedIn Weibo

Related links

Related links in nature research.

Experimental psychology: The anatomy of obedience 2015-Jul-22

Virtual reality shocker 2006-Dec-22

Related external links

UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abbott, A. Modern Milgram experiment sheds light on power of authority. Nature 530 , 394–395 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.19408

Download citation

Published : 18 February 2016

Issue Date : 25 February 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.19408

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Keith E Rice's Integrated SocioPsychology Blog & Pages

Aligning, integrating and applying the behavioural sciences

Home » Society & Community » Conformity & Obedience » Milgram’s Obedience Experiments » Milgram’s Obedience Experiments #3

Milgram’s Obedience Experiments #3

Replications of the classic study Post-1974 and the publication of Milgram’s book, replications of Milgram’s experiment became increasingly rare as the growth of ethical guidelines and increasingly-powerful ethics committees in academic establishments made it all but impossible to put participants at risk the way Milgram had. However, a number of replications were carried out in other countries and largely support Milgram’s findings as reliable . Among these replications, the percentages of participants going to 450v were:-

- 80% in Italy – Leonardo Ancona & Rosetta Pareyson , 1968

- 85% of a sample of German males – David Mantell , 1971

- 50% of a male British sample – Peter Burley & John McGuinness , 1977

- 90% of a sample of Spanish students – Bonny Miranda et al , 1981

- 85% of an Austrian sample recruited from the general public – Grete Schurz , 1985

Not all the replications were as faithful to Milgram as they could have been. One of the more concerning was that of Mitri Shanab & Khawla Yahya (1977). Working with 6-16 year-olds, they found 73% of the children gave what they believed were real electric shocks to other same gender peers. A further potential confounding variable was that the researcher was female.

One of the more interesting replications with regard to gender differences was that of Wesley Kilham & Leon Mann in Australia in 1974. They found 40% of males would go to 450v but only 16% of females. However, potential confounding variables were that participants were all first-year Psychology students and the females’ victim was female student. The lower obedience rates overall may be attributed to the notion that in Australian culture there is more of a tradition of questioning authority.