Black Frankenstein at the Bicentennial Race and political metaphor from Nat Turner to now.

Elizabeth Young

Monster metaphors matter. They show what a culture demonizes and they provide a vocabulary for those who are marked as monstrous to resist. I have been tracking a particularly revealing and protean monster metaphor for some years. Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein offers no overt discussions of racial identity for the creature who is assembled from disparate corpses and reanimated and who then rebels violently against his maker. But the figure of a Black Frankenstein monster appears with surprising frequency in U.S. culture from the nineteenth century onward, across many media, in direct and indirect references, and in works by African-American as well as white artists. Described as yellow in Shelley’s novel, tinted blue in nineteenth-century stage incarnations, and colored green in twentieth-century cinematic ones, the monster’s color has often signified metaphorically, on the domestic American scene, as Black.

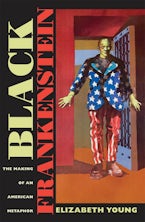

I wrote about this monster in Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor (2008), where I argued that it has long operated as a mutable political metaphor in U.S. culture. The specter of a Black Frankenstein monster—customarily, a male monster—has sometimes been invoked by political conservatives, for whom it reinforces racist connections between blackness and monstrosity. But this figure has tended to serve more effectively in radical political ways, for two reasons. It offers both a condemnation of those in power for creating conditions of monstrous violence and a defense of so-called monsters themselves. In a racist culture that already considered African-American men monstrous, the Frankenstein story has provided a way to turn an existing discourse of Black monstrosity against itself.

The specter of a Black Frankenstein monster … has sometimes been invoked by political conservatives, for whom it reinforces racist connections between blackness and monstrosity. But this figure has tended to serve more effectively in radical political ways, for two reasons. It offers both a condemnation of those in power for creating conditions of monstrous violence and a defense of so-called monsters themselves. In a racist culture that already considered African-American men monstrous, the Frankenstein story has provided a way to turn an existing discourse of Black monstrosity against itself.

In the decade since Black Frankenstein appeared, this metaphor has persisted and been reanimated in the contemporary scene. In this essay, I track some recent reappearances of the Black Frankenstein monster in American culture, first revisiting key moments in the monster’s racial genealogy: his point of origin in U.S. history; his visual transformation in horror film; and his sustained adaptation in the writing of African-American comedian and activist Dick Gregory. I revisit the monster metaphor’s past in order to think about his present and future. At its most disturbing, this is a present that makes literal the murderous consequences of equating blackness with monstrosity; at its most empowering, this is a fabulist future of revenge and renewal, as imagined by Black writers Nnedi Okorafor and Victor LaValle. The figure of a Black Frankenstein monster continues to reanimate U.S. culture in both demonizing and redemptive ways.

In 1831, Mary Shelley’s novel was republished in a new edition, with a heavily revised text and a new author’s Introduction, which described the genesis of the novel in the author’s dream about a “pale student of unhallowed arts” and “the hideous phantasm of a man” he created. 1 In America, 1831 was the year of the most famous slave revolt in U.S. history: that of Nat Turner in Southampton, Virginia. In this revolt, Turner, with the assistance of a dozen others, murdered some 60 white people; after evading authorities for weeks, he was captured, tried, and hanged. Turner’s account of the revolt, as mediated by Thomas Gray, the white man who interviewed him and transcribed his words, was the 1831 document known as The Confessions of Nat Turner .

There are numerous connections between stories of the Frankenstein monster—in Shelley’s account, a “hideous phantasm”—and Nat Turner. The Turner revolt prompted debate over emancipation in the Virginia State Legislature, including a defense of slavery by a politician named Thomas Dew. A pro-slavery apologist, Dew wrote: “To turn [a negro] loose … would be to raise up a creature resembling the splendid fiction of a recent romance; the hero of which constructs a human form with all the physical capabilities of man … [but] finds too late that he has only created a more than mortal power of doing mischief, and himself recoils from the monster which he has made.” 2 This is a reference to Frankenstein, albeit a complicated one. Dew was quoting a British politician, George Canning, who had spoken in an 1824 debate in British Parliament against emancipating West Indian slaves; his reference was most likely to the stage version of Frankenstein then popular in London. Canning used the Frankenstein story to represent the enslaved West Indian man as an irrational child who should not be freed.

In quoting Canning, Thomas Dew reinforced his pro-slavery conservatism, bringing together West Indian with North American slavery. Unlike Canning, though, Dew was writing about domestic rebellions that had already come intimately within the homes of his fellow white Virginians. He also emphasized the unstable effects of revolt on the most intimate domestic space of all: the white mind. After Nat Turner’s revolt, Dew noted, “reason was almost banished from the mind, and the imagination was suffered to conjure up the most appalling phantoms.” 3 Bringing Frankenstein to America, Thomas Dew showed how Mary Shelley’s monster could be used conservatively to condemn rebellious slaves, but he also made visible the specter of the white slave owner undone by his creation.

Meanwhile, in The Confessions of Nat Turner , Turner appeared to readers as a surprisingly sympathetic figure. Turner’s first-person narration of his rebellion seemed, in the words of one journalist, “eloquently and classically expressed.” 4 Mary Shelley’s novel offers a foundation for this idea of the slave’s eloquence. For at its center is the monster’s sympathetic first-person narrative, which not only humanizes him but also, in showing his abandonment and abuse, suggests that it is his creator, Victor, who is the more monstrous character.

Responses to the Nat Turner revolt in 1831 do not go this far. But they do show how both of these elements, already present in Mary Shelley’s novel—a sympathetic monster and an unsympathetic monstermaker—could become a touchstone for U.S. debates about slavery.

Where did this monster metaphor go after 1831? The figure of a Black Frankenstein monster appears in subsequent decades in political cartoons, oratory, poetry, and fiction. But the most famous transformation of the Frankenstein story came exactly a century later, with James Whale’s films Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Whale’s Frankenstein focuses on the monster’s creation and shows his inadvertent murder of a child, his attack on Elizabeth (the bride of the scientist, who is here named Henry) and his apparent death in a fire; in Bride of Frankenstein , the monster lives, and the evil Dr. Praetorius persuades Henry to create a female monster, whose rejection of the original monster causes him to destroy everyone except Henry and Elizabeth. These films were so successful that their imagery—the large, lumbering, square-headed monster with suture marks and neck bolts, played by Boris Karloff, and the female monster in a long white dress with a white-streaked Nefertiti hairdo, played by Elsa Lanchester—became the standard currency for popular circulation of the Frankenstein story.

The Whale Frankenstein films have multiple political connotations, including the queer resonances with which James Whale, an out gay man in homophobic Hollywood, sympathetically suffused them. My interest here is in their relation to U.S. racial politics of the 1930s, specifically the rise in lynchings and the 1931 conviction of nine young Black men known as the “Scottsboro boys.” There are, of course, no visible African-American characters in the Whale films, whose setting is an unspecified Europe and whose director and actors are English. But the films indirectly offer a surprisingly radical intervention into American iconographies of race, rape, and lynching. Within their cinematic fantasy space—or perhaps because of their cinematic fantasy space, given that more realist films of the 1930s were more cautious about racial politics—the Whale films offer an antilynching perspective.

In both Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein , for example, the monster is depicted in flight from a crowd of angry townspeople, whose pursuit of him is represented with the visual markers of a lynch mob, including barking dogs, fiery torches, and angry shouts. At one point in Bride of Frankenstein , the monster is strung up on a tree as a cluster of white people surrounds him, their anger sparked by his perceived violation of a white girl.

The monster is presented sympathetically at this moment, his iconography blended with that of Christian martyrdom. Here the Frankenstein monster meets both Christ on the cross and the victim of lynching. Whale’s monster also seems kin to that other 1930s film figure associated with blackness and violence: King Kong. Like Kong, Whale’s Frankenstein monster is as much sympathetic victim as he is source of horror, while the true location of monstrosity becomes the mob who demonizes him.

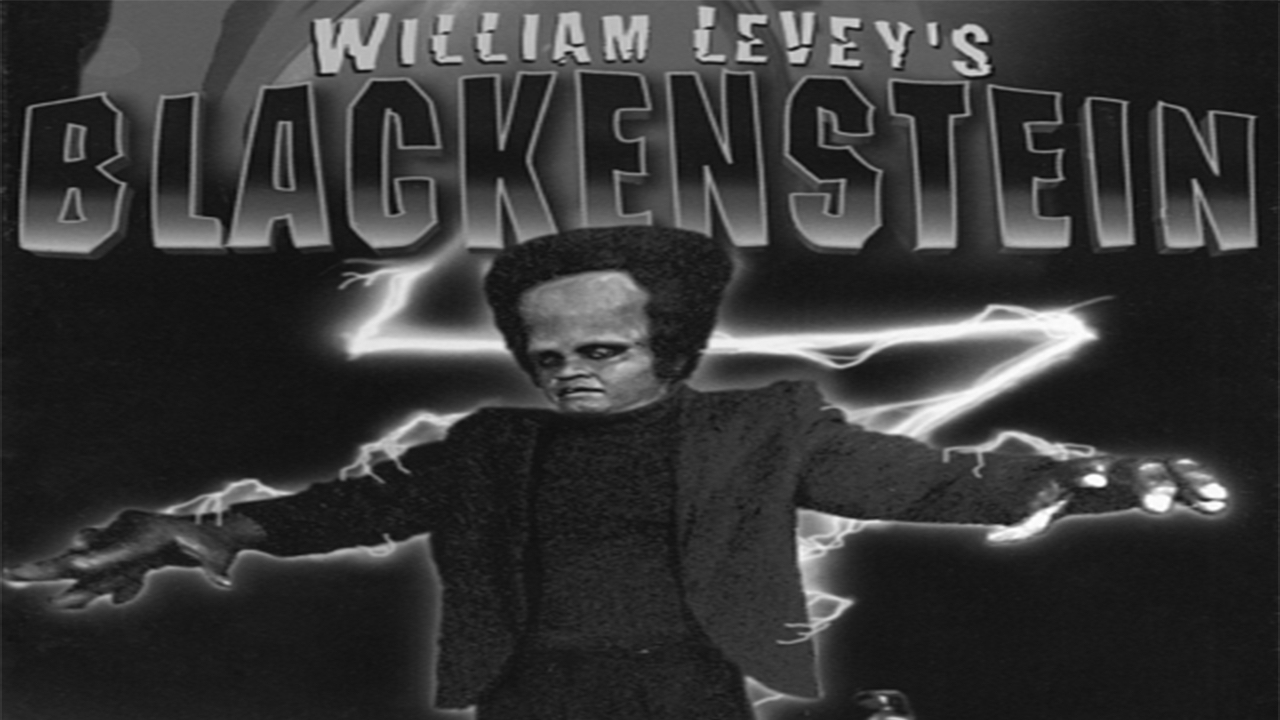

The metaphorical blackness of the Frankenstein monster in the Whale films is made literal in Blackenstein , a film in the 1970s genre of blaxploitation. About a dozen films combined blaxploitation with horror, as in 1972’s Blacula , in which an African prince, made into a vampire by a slave trader, comes back to life in present-day Los Angeles. Blackenstein , made by white filmmakers to capitalize on Blacula ’s success, was released in 1973. Set in Los Angeles, Blackenstein records the transformation of a young African-American soldier, Eddie Turner, who has just lost all his limbs fighting in Vietnam. After an operation in a V.A. hospital, Turner reemerges as a monster whose large form, lumbering gait, flat-topped head and groaning offer an affectionate parody of Boris Karloff ’s Frankenstein monster.

Blackenstein’s Afro is also a friendly take-off on the contemporary Black Power movement, while his actions situate violent rebellion as a form of political protest. For example, the film opens with scenes in which Turner, immobilized in a hospital bed, is cruelly taunted by a white orderly; when Turner is transformed into “Blackenstein,” his first act is to murder the orderly. The film’s pointed references to the Vietnam War suggest that this individual act is also a national allegory. Blackenstein’s revenge is against the white nation that condemns African-American men while making them fight its unwinnable war in Vietnam.

At the same moment that Blackenstein moved the horror of Frankenstein toward humor, another artist was exploring these connections in a sustained way. Born in St. Louis in 1932, Black comedian and activist Dick Gregory became a successful stand-up comic and then a committed Civil Rights activist; he died in August, 2017. Among his achievements, Gregory wrote or co-wrote more than a dozen books, which remain an underappreciated part of his career. He explicitly developed a narrative of a Black Frankenstein monster in at least a half-dozen works of autobiography, essays, and comedy performances in the 1960s and 1970s.

Gregory’s literary use of the monster began in his 1964 autobiography, wherein he describes going to see Frankenstein as a child at a movie theater in St. Louis: “We used to root for Frankenstein, sat there and yelled, ‘Get him, Frankie baby.’” 5 In a 1968 essay collection, he expanded this memory into a political allegory:

I realize why I wasn’t frightened. Somehow I unconsciously realized that the Frankenstein monster was chasing what was chasing me. Here was a monster, created by a white man, turning upon his creator. The horror movie was merely a parable of life in the ghetto. The monstrous life of the ghetto has been created by the white man. Only now in the city of chaos are we seeing the monster created by oppression turn upon its creator. 6

In Gregory’s turn from personal to collective struggle, he recast the Frankenstein monster as the “monstrous life of the ghetto” and his rebellion as the violence of “the city of chaos,” presumably a reference to contemporary uprisings in Watts, Newark, Detroit and elsewhere. In 1971, his “parable” became a prophecy of widespread Black resistance: “The old Frankenstein movies are parables of America’s destruction … America has become a mad scientist’s laboratory. The monster must act on his own. The monster has turned and cannot be expected to be the same again.” 7

Gregory’s use of the Frankenstein monster was complementary with his larger strategy of reappropriating existing images and norms. These ranged from Uncle Sam—in his first book, he posed in a photograph dressed as Uncle Sam, sitting coolly atop a globe—to the toxic word “nigger,” which he chose as the title of his first autobiography as a challenge to white readers; as he later wrote, “I used that word so that White folks couldn’t find power in it.” 8 In the case of the Frankenstein monster, Gregory altered a familiar symbol already far more congenial to radical reappropriation. Signifying on the James Whale films, Gregory used the monster as a symbol through which to narrate his own biography and offer a sustained critique of white America.

For Gregory, an African-American writer and performer—and for Glaser, a white artist—the monster is quintessentially both American and African-American. Leaving a jail cell, this Black Frankenstein is, in the era of Civil Rights and Black Power, free at last.

An image dramatizes the force of this appropriation, from a 1970 recording of a Gregory comedy performance entitled Dick Gregory’s Frankenstein . The art on the double-sized album jacket was created by renowned graphic designer Milton Glaser. His image shows a Frankenstein monster, with the square head, bolted neck, and green skin of Boris Karloff, dressed in an American flag and emerging through the threshold of a jail cell. This image reappropriates the iconography of the American flag together with that of the Frankenstein monster. For Gregory, an African-American writer and performer—and for Glaser, a white artist—the monster is quintessentially both American and African-American. Leaving a jail cell, this Black Frankenstein is, in the era of Civil Rights and Black Power, free at last.

Where is the Black Frankenstein monster now? I have shown how this metaphoric monster moves in U.S. culture from antebellum slavery in the 1830s to lynching in the 1930s, from slave revolt to Civil Rights and Black Power, and from oratory through film to stand-up comedy. This is a cultural genealogy with interracial authorship and changeable politics, albeit asymmetrical ones. While the original uses of the metaphor in U.S. culture in the aftermath of the Nat Turner revolt are conservative, my other examples show its potential for radical critique—both a critique of white power and a sympathetic reclaiming of so-called monsters.

A contemporary anatomy of this metaphor includes radical potential, but it must start with its most negative and material connections to violence. The racist dimensions of the Black Frankenstein metaphor remain tragically salient in the discourse of white American police officers who have murdered young Black men. The clearest example is in the testimony of officer Darren Wilson about his murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in summer 2014: “The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.” 9 Wilson does not specify the terms of his simile— “like a demon”—as the Frankenstein monster. But his testimony bespeaks the ongoing consequences of a gothicized language of Black monstrosity. The Black man who is seen as monstrously “angry” by white men continues to prompt murderous real-life violence.

At the same time, the figure of a Black Frankenstein monster has generated new oppositional uses by African-American and white artists. Painter Kerry James Marshall entitled two large, nearnude portraits of a contemporary African-American man and woman Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein (2009); these titles are represented within the paintings as wall labels adjacent to the figures, suggesting their cultural labeling as monsters. Marshall follows other contemporary African-American artists who have signified on the Frankenstein tradition, including Glenn Ligon’s Study for Frankenstein #1 (1991), a text-based painting that repeats one poignant sentence in the monster’s voice from Shelley’s novel, and, a generation earlier, Ed Bereal’s comically remixed movie still Self-Portrait (1968), in which he inserts himself into a still from Son of Frankenstein . In the visual medium of graphic narrative, Emil Ferris includes Black Frankenstein imagery in her recent graphic novel My Favorite Thing is Monsters (2017). In delicately drawn panels, Ferris, who is white, sympathetically links an ostracized Black male character, Franklin, to the Karloff monster of the Whale films.

Two significant transformations of the Black Frankenstein metaphor emerge in the writings of African-American authors working in science fiction and fantasy genres and under the rubric of “Afrofuturism,” which was first defined by Mark Dery in 1994 as “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes…and more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future.” 10 Afrofuturism includes music, film, and visual art, as well as literature; major recent writers are Samuel Delany and Octavia Butler, while Afrofuturism’s literary antecedents include W.E.B. Du Bois and Ralph Ellison.

Nnedi Okorafor, a Nigerian-American writer of science fiction and fantasy, works with “a prosthetically enhanced future” in her 2015 novel The Book of Phoenix . Its narrator is a Black woman who is created and mistreated by a sinister high-tech corporation and who then wreaks elaborate revenge on it; its plot toggles between the U.S. and West Africa and its timeframe between near and far future. A prequel to her previous novel, Who Fears Death (2010), The Book of Phoenix stands on its own. It also stands alongside Shelley’s Frankenstein , whose narrative Okorafor intermittently but unmistakably evokes, and whose metaphorically Black monster she transforms.

Here is the novel’s protagonist, Phoenix, describing her upbringing in terms that echo those of the self-educated monster in Shelley’s novel: “I was an abomination. I’d read many books and this was clear to me.” Phoenix’s declaration of revenge also echoes the rage of Shelley’s monster: “I am the villain in the story. Haven’t you figured it out yet? Nothing good can come from unnatural bonding and creation. Only violence. I am a harbinger of violence. Watch what happens wherever I go.” Okorafor locates the origin of this character within a framework of the African diaspora: “I was nothing but the result of a slurry of African DNA and cells. They constructed [me] with materials of over ten Africans .… An African American woman carried me to term, and when I was born, she wanted to keep me. They wouldn’t even let her kiss me goodbye.” 11 In contrast to Victor Frankenstein’s abandonment of his creation, Phoenix’s mother longs to keep her, and her forcible separation from her child echoes the violations of slavery in the diaspora.

This mother-daughter plot also alters the gender dynamics of Mary Shelley’s novel, which focuses on men. This change, though, is faithful to other elements of the original Frankenstein . Feminist critics have shown how the theme of maternal loss suffuses the original novel, linked biographically to Shelley’s own loss of a baby, as well as to the death of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, after giving birth to her. Making visible this feminist theme already evoked in Frankenstein , Okorafor sutures the earlier novel to fabulist cultural critique. Seen through The Book of Phoenix , Shelley’s Frankenstein emerges as part of the transatlantic pre-history of Afrofuturism.

While Okorafor intermittently evokes elements of Frankenstein , Victor LaValle engages in a sustained way with Shelley’s novel. LaValle, an African-American novelist who writes in both “literary” and “genre” fiction, has shown a particular interest in signifying upon horror classics.

For example, his novella The Ballad of Black Tom (2016) explicitly revises H. P. Lovecraft’s story “The Horror of Red Hook,” with a focus on Lovecraft’s racism. Black Tom also briefly evokes Frankenstein , when its titular character, a Black man who becomes violent after mistreatment, explains that “[F]inding myself unsympathized with, [I] wished to … spread havoc and destruction around me”; when his white interlocutor remarks, “You’re a monster, then,” Tom replies, “I was made one.” 12 Victor LaValle’s Destroyer (2017) represents LaValle’s dedicated project of signifying upon Frankenstein in the form of a six-issue comic series.

Destroyer contains two Frankenstein creatures. One is the recognizable monster of Shelley’s novel, who appears at the start of the comic, alive on an ice floe, and wreaks more revenge on the novel’s contemporary world. The second monster is entirely new: LaValle generates the plot of an African-American woman scientist—conveniently, a descendant of the original Frankenstein family—who is consumed with grief when her twelve-year-old son, Akai, is killed by white police, and who then decides to reanimate him with a 3-D printer and other technological tools. In an author’s note appended to the first issue, LaValle writes of the comic’s origin in his response to contemporary violence: “[A] soul-crushing sense of loss—came to me … as I watched the news … and tallied the number of black lives lost at the wrong end of a policeman’s fear.” 13 The character of Akai memorializes those lives lost, particularly the lives of Black boys seen only as violent adult men and destroyed. A National Public Radio story on Destroyer was succinctly entitled “Updating Frankenstein for the Age of Black Lives Matter.” 14

As the Black Frankenstein genealogy preceding LaValle shows, this “updating” is less a collision between two disjunct worlds than an extension of the racial politics already implicit in Shelley’s novel. In his author’s note, LaValle links his outrage at watching the news to his interest in Shelley: “The story we’re telling in Destroyer came to me … almost like a fever dream. Like Mary Shelley, I would tell the story of a mother who lost her child far too soon. …. [M]y protagonist, Professor Josephine Baker …. would do as Mary’s creation had done, she would bring the dead back from across the veil … She would create life, but she would use that creation for vengeance.” This story reprises Shelley’s own famous account of the origin of the novel in her dream of the “pale student” and the “hideous phantasm of a man” he created. LaValle ingeniously remasters this origin story, in several senses—his “creation” is a boy, rather than a man; he is beloved, rather than abandoned by his maker; and he is reanimated out of love, not scientific hubris.

Like Okorafor, LaValle alters the gender as well as racial frameworks of the novel. His version of the “pale” creator, meanwhile, is a Black woman, who is both grieving mother and academic scientist. Her name, “Professor Josephine Baker,” provides a direct connection to the history of Black women’s art and activism. The visionary monster story of LaValle’s Destroyer is organized by a Black woman’s creative brilliance as well as her sense of maternal loss. This is a combination he locates in the nineteenth century legacy of Mary Shelley, names for the 20th-century heroine Josephine Baker, and resituates in a contemporary African-American world.

LaValle ingeniously remasters [Shelley’s] origin story, in several senses—his “creation” is a boy, rather than a man; he is beloved, rather than abandoned by his maker; and he is reanimated out of love, not scientific hubris.

LaValle, like Okorafor, adapts a long legacy of Black Frankenstein monsters, but both writers challenge this legacy as well. Many Black Frankenstein metaphors, images, and narratives remain structured by the negative relation between monster and monster-maker; like James Whale’s Frankenstein films or Blackenstein , they situate blackness in reactive relation to whiteness. By contrast, Okorafor and LaValle take up Dick Gregory’s challenge—“The monster … cannot be expected to be the same again”—to imagine new futures as well as new pasts for the metaphor of the Black Frankenstein monster. In so doing, they show the necessity as well as the vitality of this metaphor, in a world in which the perception of Black monstrosity continues to have literally murderous effects. As a third century of Frankenstein stories begins, the undead monster prompts an ever-undead metaphor, and writers and artists remain vital to showing how Black lives as well as monsters matter.

1. Mary Shelley, F rankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism , ed. J. Paul Hunter (2nd edition; New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2012), 168.

2. Thomas Dew, Review of the Debate in the Virginia Legislature of 1831 and 1832 (Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1970), 105.

3. Dew , Review, 6.

4. [Anonymous], Richmond Enquirer (1831), quoted in The Southampton Slave Revolt of 1831 , ed. Henry Irving Tragle (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1971), 143.

5. Dick Gregory with Robert Lipsyte, Nigger: An Autobiography (New York: Pocket, 1965), 39.

6. Dick Gregory, The Shadow that Scares Me , ed. James R. McGraw (New York: Pocket, 1968), 168.

7. Richard Claxton Gregory, No More Lies: The Myth and the Reality of American History , ed. James R. McGraw (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 278-79.

8. Dick Gregory with Sheila P. Moses, Callus on My Soul: A Memoir (Atlanta: Longstreet, 2000), 120.

9. Quoted in Damien Cave, “Officer Darren Wilson’s Grand Jury Testimony in Ferguson, Mo., Shooting,” New York Times , November 25, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/ interactive/2014/11/25/us/darren-wilson-testimony-ferguson-shooting.html.

10. Mark Dery, “Black to the Future: Afro-Futurism 1.0” (1994), reprinted in Afro-Future Females: Black Writers Chart Science Fiction’s Newest New-Wave Trajectory , ed. Marleen S. Barr (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2008), 8.

11. Nnedi Okorafor, The Book of Phoenix (New York: DAW Books, 2015), 7, 85, and 146-47.

12. Victor LaValle, The Ballad of Black Tom (New York: Tor, 2016), 130.

13. Victor LaValle, Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 , illustrated by Dietrich Smith with Joana Lafuente (BOOM! Studios, May 2017).

14. Gene Demby, “Updating Frankenstein for the Age of Black Lives Matter,” Code Switch , National Public Radio, June 22, 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/ 2017/06/22/533512719/updating-frankenstein-for-the-age-of-black-lives-matter.

Comments Closed

About the common reader.

The Common Reader , a publication of Washington University in St. Louis, offers the best in reviews, articles and creative non-fiction engaging the essential debates and issues of our time.

The Current Issue

The Common Reader goes to Chicago to check in with the Democratic Party.

Never see this message again.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Black Frankenstein

The making of an american metaphor.

- Elizabeth Young

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: New York University Press

- Copyright year: 2008

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Other: 18 black and white illustrations

- Keywords: African ; American ; Americans ; appears ; black ; both ; culture ; Elizabeth ; essays ; fiction ; figure ; film ; Frankenstein ; frequency ; identifies ; interprets ; media ; monster ; nineteenth- ; oratory ; other ; painting ; surprising ; throughout ; twentieth-century ; US ; whites ; with ; works ; Young

- Published: August 10, 2008

- ISBN: 9781479809608

Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature: Black Frankenstein

- NLM Online Exhibit This link opens in a new window

- Mary Shelley Birthday Party

- Black Frankenstein

- FrankenMeme Contest

- Panel Discussion

- On its way...

- Research This link opens in a new window

Black Frankenstein stories, Young argues, effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slaveowner; and they expose the instability of white power. The black Frankenstein's monster has served as a powerful metaphor for reinforcing racial hierarchy—and as an even more powerful metaphor for shaping anti-racist critique. Illuminating the power of parody and reappropriation, Black Frankenstein tells the story of a metaphor that continues to matter to literature, culture, aesthetics, and politics.

Read the eBook

Find the print book

Young is the author of Disarming the Nation: Women's Writing and the American Civil War (University of Chicago Press, 1999), which discusses works ranging from the novels Little Women and Gone with the Wind to African American women's memoirs of the war to narratives of women who cross-dressed as male soldiers. The Journal of American History has hailed Young's first book as "an illuminating analysis of women's Civil War literature that successfully challenges assertions that a heroic masculinity constituted the war's literary heritage." Disarming the Nation was named an Outstanding Academic Title by the journal Choice , and Young was honored with Mount Holyoke's Meribeth E. Cameron Prize for Faculty Scholarship.

Young is also the author of Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor (New York University Press, 2008), a study of race and the Frankenstein metaphor in American literature, culture, and film of the last two centuries. She is the co-author, with Anthony W. Lee, of On Alexander Gardner's "Photographic Sketch Book" of the Civil War (University of California Press, 2007), a study of the relation between images and words in one of the most famous volumes of Civil War photographs. She has contributed chapters to The End of Cinema as We Know It (New York University Press, 2002), Subjects and Citizens: Nation, Race, and Gender from "Oronooko" to Anita Hill (Duke University Press, 1995), and The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film (University of Texas Press, 1996). Her articles have appeared in the American Quarterly and Camera Obscura .

- << Previous: Mary Shelley Birthday Party

- Next: FrankenMeme Contest >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/frankenstein-programming

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor

In this Book

- Elizabeth Young

- Published by: NYU Press

For all the scholarship devoted to Mary Shelley's English novel Frankenstein, there has been surprisingly little attention paid to its role in American culture, and virtually none to its racial resonances in the United States. In Black Frankenstein , Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans. Black Frankenstein stories, Young argues, effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slaveowner; and they expose the instability of white power. The black Frankenstein's monster has served as a powerful metaphor for reinforcing racial hierarchy—and as an even more powerful metaphor for shaping anti-racist critique. Illuminating the power of parody and reappropriation, Black Frankenstein tells the story of a metaphor that continues to matter to literature, culture, aesthetics, and politics.

- Table of Contents

- Half-Title Page, Title Page, Copyright, Dedication

- pp. vii-viii

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 United States of Frankenstein

- 2 Black Monsters, Dead Metaphors

- 3 The Signifying Monster

- pp. 107-158

- 4 Souls on Ice

- pp. 159-218

- pp. 219-230

- pp. 231-292

- pp. 293-307

- About the Author

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

October 12, 2010

Black frankenstein , by elizabeth young.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is one of the most thoroughly examined books in literary history. Its themes and manifestations permeate our culture and have yielded a massive and ever-growing body of work. Elizabeth Young’s Black Frankenstein, The Making of an American Metaphor (University of New York Press, 2008) is an important addition as it effectively breaks new ground, proposing a deep analysis of Frankenstein as a racial metaphor in American culture.

Perhaps the first metaphorical reference to Frankenstein came in 1824, shortly after Mary Shelley’s novel of 1818 had been adapted, with phenomenal success, to the theater. George Canning, the British Foreign Secretary, addressing the issue of the West Indian slave trade, referred to “ the splendid fiction of a recent romance ” in which a dangerous creature is “ raised up ” with “ the thews and sinews of a giant ” but with no perception of right and wrong. Canning, an abolitionist, was promulgating a slow and gradual approach to ending slavery, paternalistically warning against immediate emancipation of the Negro who possessed “the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child ”.

Canning’s statement, without benefit of context, was used in America by proslavery apologist Thomas Dew as a vivid illustration of the dire consequences of abolition, and with it, the Black Frankenstein entered American consciousness.

Elizabeth Young tracks the onset of the metaphorical Monster and its affinity with the vocabulary of racial rebellion through political cartoons, editorial and fictional uses. In 1829, for instance, the language of Mary’s Monster, cursing his wretchedness, is identical to that found in an antislavery manifesto of free African American David Walker who wrote of “the Coloured people” as “ miserable, wretched, degraded and abject ”. The Monster spoke of revenge on his creator much like Walker’s admonition that, “ some of you… will yet curse the day you were born .”

Young grippingly documents the Frankenstein parable in American fiction, touching, among others, on the automaton in Herman Melville’s The Bell-Tower (1855), Stephen Crane’s The Monster (1898) about a black coachman disfigured in a fire while saving the life of a white child, and The Sport of Gods (1902) by Paul Laurence Dunbar, that namechecks Frankenstein in reference to its murderous protagonist, a monster made by racism. Moving on to films, Young examines Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) as a monster movie, replete with its ugly stereotypes, and James Whale’s Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein playing out against the backdrop of the 1931 Scottsboro trial and the failure of an anti-lynching bill in 1935. Theme obliging, even the execrable Blackenstein (1973) merits analysis.

The book wraps with a fascinating exploration of comedian and activist Dick Gregory’s own explorations of the Black Frankenstein concept.

“ I told Momma, ‘ I just saw Frankenstein and the monster didn’t scare me’¨, wrote Gregory in his essay, Dreaming of a Movie (1968). “ But now that I look back, I realize why I wasn’t frightened. Somehow I subconsciously realized that the Frankenstein monster was chasing what was chasing me. Here was a monster, created by a white man, turning upon his creator. The horror movie was merely a parable for life in the ghetto. The monstrous life of the ghetto has been created by the white man. Only now in the city of chaos are we seeing the monster created by oppression turn upon his creator. ”

Note, the cover of Black Frankenstein uses Milton Glaser’s art from the inside-cover spread for Dick Gregory’s Frankenstein live album of 1971.

In an afterword, Young reflects briefly on Frankenstein references in the contemporary art of Glenn Ligon, pointing, perhaps, to the need for a full-blown survey of Frankenstein in the visual arts.

Black Frankenstein is a relentlessly serious, scholarly tome and the reader best come prepared to be challenged by some of its concepts, and provoked by some of its ideas. A chapter dealing with metaphor-making, the definition of monster metaphors, meta-metaphorical meanings and Frankenstein as a metaphor for metaphor itself demands careful reading and will no doubt boggle a casual reader.

On the other hand, if you’re willing to wade into this robust, remarkably researched study of Frankenstein’s cultural and racial significance in America, you’ll find there is much to discover here, and much to think about. Elizabeth Young’s Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor is a necessary and important addition to Frankenstein scholarship.

Elizabeth Young’s Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor (University of New York Press, 2008).

A short profile of author Elizabeth Young .

Read the introduction to Black Frankenstein , courtesy of NYU Press.

Black Frankenstein on Google Books .

Questioning Authority , a short interview with author Elizabeth Young.

New York University Press page for Black Frankenstein

Labels: Art and Illustration , Books , Studies

No comments:

Post a Comment

Visit our Companion Blog!

Blog Archive

Labels: films.

- • Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) (11)

- • After Frankenstein (2010) (1)

- • Assignment Terror (1970) (1)

- • Blue skies (1946) (2)

- • Bride of Frankenstein (1935) (81)

- • CGI Frankenstein (1998) (2)

- • Death Race 2000 (1975) (1)

- • Dracula vs. Frankenstein (1971) (1)

- • El Aullido del diablo (1988) (1)

- • El castillo de los monstruos (1958) (2)

- • Fanny Hill Meets Dr. Erotico (1967) (1)

- • Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) (1)

- • Frankenhood (2009) (1)

- • Frankenstein (1910) (15)

- • Frankenstein (1931) (90)

- • Frankenstein (2004) (1)

- • Frankenstein (ITV 2007) (1)

- • Frankenstein (Matinee Theater) 1957 (4)

- • Frankenstein (Mystery and Imagination (2)

- • Frankenstein (National Theatre 2011) (2)

- • Frankenstein (Tales of Tomorrow (2)

- • Frankenstein 1970 (1958) (6)

- • Frankenstein all'italiano (1975) (1)

- • Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974) (5)

- • Frankenstein Conquers The World (1965) (4)

- • Frankenstein Created Woman (1967) (1)

- • Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man (1943) (15)

- • Frankenstein Rising (2008) (1)

- • Frankenstein Unlimited (2009) (2)

- • Frankenstein: The True Story (1973) (2)

- • Frankenstein's Army (2012) (2)

- • Frankenstein's Bloody Terror (1968) (1)

- • Frankenstein's Cat (1942) (1)

- • Frankenstein's Daughter (1958) (4)

- • Frankenstein's Wedding (2011) (3)

- • G Man Jitters (1939) (1)

- • Gods and Monsters (1998) (1)

- • Gothic (1986) (1)

- • Gruesomestein's Monsters (2005) (1)

- • Haram alek (1953) (3)

- • Hellzapoppin' (1941) (1)

- • Homunculus (1916) (2)

- • House of Dracula (1945) (7)

- • House of Frankenstein (1944) (4)

- • House of the Wolf Man (2009) (2)

- • How To Make a Monster (1958) (2)

- • I Frankenstein (1)

- • I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957) (5)

- • Igor (2008) (2)

- • Il Mostro di Frankenstein (1920) (5)

- • La Figlia di Frankenstein (1971) (3)

- • Life Without Soul (1915) (5)

- • Los Monstruos del Terror (1969) (1)

- • Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1994) (1)

- • Mickey's Gala Premiere (1933) (1)

- • Mistress Frankenstein (2000) (1)

- • Monster Brawl (2011) (2)

- • Porky's Movie Mystery (1939) (1)

- • Route 66: Lizard's Leg and Owlet's Wing (1962) (1)

- • Runaway Brain (1995) (3)

- • Santo vs la hija de Frankestein (1971) (1)

- • Sevimli Frankenstayn (1975) (1)

- • Son of Frankenstein (1939) (27)

- • Splice (2010) (1)

- • Tales of Frankenstein (1958) (3)

- • Tender Son - The Frankenstein Project (2010) (1)

- • Terror of Frankenstein (see Victor Frankenstein) (1)

- • The Bride (1985) (1)

- • The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) (21)

- • The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) (1)

- • The Frankenstein Theory (2013) (1)

- • The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) (5)

- • The Halloween That Almost Wasn't (1979) (1)

- • The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) (3)

- • The Incredible Hulk (1)

- • The Man Who Saw Frankenstein Cry (2010) (1)

- • The Monster Squad (1987) (2)

- • The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) (7)

- • The Vindicator (1986) (1)

- • The Walking Dead (1936) (2)

- • Third Dimensional Murder (1941) (2)

- • Thursday's Child (1943) (2)

- • Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl (2009) (4)

- • Van Helsing (2004) (1)

- • Victor Frankenstein (1977) (1)

- • Young Frankenstein (1974) (4)

- CARRY ON SCREAMING (1966) (3)

- DOUBLE DOOR (1934) (1)

- FRANKENSTEIN CANNOT BE STOPPED (2014) (1)

- FRANKENSTEIN MD (2014) (1)

- FRANKENSTEIN TRESTLE. THE (1899) (1)

- FRANKENSTEIN'S AUNT (1987) (1)

- FRANKENWEENIE (2012) (2)

- HOLLYWOOD CAPERS (1935) (1)

- I WAS A TEENAGE MONSTER (THE MONKEES) (1)

- MYSTERY OF THE HAUNTED HOUSE (THE HARDY BOYS/NANCY DREW MYSTERIES) (1)

- Penny Dreadful (2014) (4)

- SHERLOCK HOLMES VS FRANKENSTEIN (2)

- THE GREAT PIGGY BANK ROBBERY (1946) (1)

- THE SKELETON IN THE CUPBOARD SAVE (1943) (1)

- VICTOR FRANKENSTEIN (2015) (1)

Labels: General

- Advertising (15)

- Animation (21)

- Arsenic and Old Lace (1)

- Art and Illustration (260)

- Awards (23)

- Bela Lugosi (9)

- Blog-a-Thon (25)

- Boris Karloff (51)

- BORIS KARLOFF BLOGATHON (12)

- Christopher Lee (9)

- Comics (63)

- Covers (103)

- Dick Briefer (9)

- Don Post (11)

- Dr. Moreau (2)

- Fantasia (9)

- Feg Murray (12)

- Fiction (5)

- Frankensteinian (14)

- Glenn Strange (9)

- Guest Blogger (13)

- Hammer Films (17)

- History (12)

- Illustration (9)

- Jack Pierce (12)

- James Whale (11)

- Lon Chaney Jr. (6)

- Mary Shelley (43)

- Memorabilia (10)

- Musicals (8)

- On This Day (48)

- Peter Cushing (22)

- Peter Cushing Blogathon (8)

- Places (13)

- Pop Culture (108)

- Posters (81)

- Sculpture (12)

- Shock Theater (3)

- Shuler Hensley (6)

- Silent Films (8)

- Studies (9)

- The Munsters (5)

- Theater (34)

- Warren Magazines (21)

- Young Frankenstein: Musical (7)

Frankenstein Image Blog!

They Say...

"Outstanding, must-read. A mind blowing treasure trove of all things fantastically Frankenstein." — The Horrors of It All

“ A wonderful blog, as fun as it is informative, and always well written and designed… always teaches me something or sharpens my focus on some detail or other.” — Tim Lucas, Video WatchBlog

“ I continue to be amazed, amused, delighted, and awed by Pierre Fournier's blog, Frankensteinia… No one does it better." — Susan Tyler Hitchcock, author of Frankenstein, A Cultural History , Monster Sightings

“ Beautiful and evocative writing style… as near perfect a Frankenstein experience as I could wish for. Bravo!" — Jeff Cohen, Vitaphone Varieties

“ Inestimable… Mind-opening" — Arbogast on Film

“Intelligent and well-presented… avid in seeking out a wide range of examples... A useful research aid for those seeking to survey the uses to which the Frankenstein monster is still being put in popular culture .” — Intute, Arts & Humanities

“Outstanding and intelligent… I am insane with giddiness that "It's ALIVE!!"

— Max, The Drunken Severed Head

- And Everything Else Too

- arts•meme

- Big V Riot Squad

- Countdown to Halloween

- Dwrayger Dungeon

- El Desván del Abuelito

- Fantasy Ink

- Greenbriar Picture Shows

- Here Lies Richard Sala

- Kindertrauma

- MONSTER CRAZY!

- Monsterminions

- Pappy's Golden Age Comics

- Scared Silly

- The Chiseler

- The Collinsport Historical Society

- The Horrors of It All

- The Pneumatic Rolling-Sphere Carrier Delusion

- This isn't happiness

- Tim Lucas Video WatchBlog

- Voyages Extraordinaires

- Wrong Side of the Art

- Creepy Classics & Monster Bash

- Fantasia Festival

- Frankenstein Films

- George Chastain

- Official Boris Karloff Home Page

- The Official Hammer Films Site

- The Rondo Awards

- The Spooky Isles

- Classic Horror Film Board

- Universal Monster Army

- Latarnia Forums

All content on this site is copyrighted and/or trademarked, and all rights are reserved by the respective authors. Text posted here may not be reproduced or reblogged without permission. Visuals and references are presented here as quotes under Fair Use for the purpose of scholarship, information or review.

Black Frankenstein

The making of an american metaphor.

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

For all the scholarship devoted to Mary Shelley's English novel Frankenstein, there has been surprisingly little attention paid to its role in American culture, and virtually none to its racial resonances in the United States. In Black Frankenstein, Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans. Black Frankenstein stories, Young argues, effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slaveowner; and they expose the instability of white power. The black Frankenstein's monster has served as a powerful metaphor for reinforcing racial hierarchy—and as an even more powerful metaphor for shaping anti-racist critique. Illuminating the power of parody and reappropriation, Black Frankenstein tells the story of a metaphor that continues to matter to literature, culture, aesthetics, and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Information, united states of frankenstein.

Slavery is everywhere the pet monster of the American people.

In dealing with a negro we must remember that we are dealing with a being possessing the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child. To turn him loose in the manhood of his physical passions… would be to raise up a creature resembling the splendid fiction of a recent romance; the hero of which constructs a human form with all the physical capabilities of man, and with the thews and sinews of a giant, but being unable to impart to the work of his hands a perception of right and wrong, he finds too late that he has only created a more than mortal power of doing mischief, and himself recoils from The monster which he has made. 2

[W]hat is the use of living, when in fact I am dead. But remember, Americans, that as miserable, wretched, degraded and abject as you have made us in preceding and, in this generation, to support you and your families, that some of you, (whites) on the continent of America, will yet curse the day that you ever were born. (72)

On The Site

- America and the Long 19th Century

- american studies

Black Frankenstein

The Making of an American Metaphor

by Elizabeth Young

Published by: NYU Press

Series: America and the Long 19th Century

Imprint: NYU Press

336 Pages , 6.00 x 9.00 in , 18 black and white illustrations

- 9780814797167

- Published: August 2008

- 9780814797150

- 9780814745373

Request Exam or Desk Copy

- Description

For all the scholarship devoted to Mary Shelley's English novel Frankenstein, there has been surprisingly little attention paid to its role in American culture, and virtually none to its racial resonances in the United States. In Black Frankenstein , Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans. Black Frankenstein stories, Young argues, effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slaveowner; and they expose the instability of white power. The black Frankenstein's monster has served as a powerful metaphor for reinforcing racial hierarchy—and as an even more powerful metaphor for shaping anti-racist critique. Illuminating the power of parody and reappropriation, Black Frankenstein tells the story of a metaphor that continues to matter to literature, culture, aesthetics, and politics.

Elizabeth Young is Professor of English and Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of Disarming the Nation: Women's Writing and the American Civil War and co-author of On Alexander Gardner's ""Photographic Sketch Book"" of the Civil War.

"Young encourages readers to use her work to further develop the idea of the Frankenstein metaphor. She has given scholars of literature and metaphorical studies an excellent place to begin." ~Edward Dauterich, African American Review

"A subtle, complex, and deeply read romp through the last two centuries of transatlantic literary and cultural history. Truly eye-opening and provocative." ~Eric Lott,University of Virginia

"In Black Frankenstein, Young tears apart and rearranges the monster we think we know into something entirely fresh and challenging. This excellent and provocative book offers a compelling lesson in the political and cultural uses of a metaphor organized by design, as well as unconsciously, into a racial paradigm." ~Eric J. Sundquist,author of Strangers in the Land: Blacks, Jews, Post-Holocaust America

"Youngs & black Frankenstein monster becomes a powerful metaphor for negotiating the racial anxieties of modern America. As the author recounts, the figure appears in both racist and antiracist discourses, exhibiting the powerful mobility of the monster metaphor as well as its popular appeal. Young combines sharp analysis with her amazing research, noteworthy for its breadth and scope, to demonstrate the depths to which this image has penetrated American racial cultures. Whether she is examining novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar, filmmaker Mel Brooks, or comedian Dick Gregory, Young offers astute readings of the cultural text and its racial underpinnings. Building on recent work by Paul Gilroy, Teresa Goddu, Toni Morrison, Michael Hardt, and Antonio Negri, this book provides a compelling new vision of the monster we thought we knew so well. Highly recommended." ~Choice

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Oct 26, 2018 · In the decade since Black Frankenstein appeared, this metaphor has persisted and been reanimated in the contemporary scene. In this essay, I track some recent reappearances of the Black Frankenstein monster in American culture, first revisiting key moments in the monster’s racial genealogy: his point of origin in U.S. history; his visual transformation in horror film; and his sustained ...

Aug 10, 2008 · In Black Frankenstein , Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans.

Feb 22, 2024 · In Black Frankenstein, Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans.

In Black Frankenstein, Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans.

Oct 12, 2010 · The book wraps with a fascinating exploration of comedian and activist Dick Gregory’s own explorations of the Black Frankenstein concept. “I told Momma, ‘ I just saw Frankenstein and the monster didn’t scare me’¨, wrote Gregory in his essay, Dreaming of a Movie (1968). “ But now that I look back, I realize why I wasn’t frightened ...

In Black Frankenstein, Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans.

Aug 10, 2008 · In Black Frankenstein, Elizabeth Young identifies and interprets the figure of a black American Frankenstein monster as it appears with surprising frequency throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century U.S. culture, in fiction, film, essays, oratory, painting, and other media, and in works by both whites and African Americans.

For all the scholarship devoted to Mary Shelley's English novel Frankenstein, there has been surprisingly little attention paid to its role in American cultu...

Aug 10, 2008 · List of Illustrations Acknowledgments Introduction 1 United States of Frankenstein 2 Black Monsters, Dead Metaphors 3 The Signifying Monster 4 Souls on Ice Afterword Notes Index About the Author

Dec 1, 2009 · Although Young never releases her hold on the racial trajectory of Frankenstein's U.S. tour (she includes an extended critique of the 1973 blaxploitation film Blackenstein that alludes to, among other things, the uses of the Afro hairstyle cross-referenced with the monster's cinematic hair), the way the foundational notion of metaphor is explored in the book inevitably leads us in other ...