Humanizing the heroin epidemic: a photo essay

Faculty, Journalism and Communication Studies, Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Disclosure statement

This work was supported by a Katalyst Grant at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey, B.C. where Aaron is a faculty member in the Journalism and Communication Studies department.

View all partners

For over a year, I’ve been documenting the lives of three long-term drug users – Marie, Cheryl and Johnny – who are participating in Vancouver’s heroin-assisted clinical study and program .

In recent years, heroin use in North America has exploded into an “epidemic.” At the same time, policymakers and the public have clashed over how to properly treat this public health scourge. Many heroin users receive methadone and other forms of treatment. However, some of the most vulnerable addicts haven’t responded to medication and detox.

I spent weeks building a rapport and trust with Marie, Cheryl and Johnny, who’ve all been addicted to heroin for years. They’ve each repeatedly tried detox and methadone and have been unable to stop using heroin.

In a sense, heroin-assisted treatment, a science-based, compassionate approach, is their last resort.

Those involved in the program – often users who haven’t sufficiently responded to other forms of treatment – receive pharmacological heroin in a clinical setting. While these programs have long been recognized as scientifically sound and cost-saving in countries like Switzerland, the Netherlands and Denmark, heroin-assisted treatment is only beginning to be offered in North America.

At first, the three subjects allowed me to take photos of them self-injecting their medication at Providence Health Care’s Crosstown Clinic in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Slowly, over a period of weeks and months, they let me document their lives outside the clinic.

While I hoped to inform the public about heroin-assisted treatment, I also wanted to see if I could create visual counter-narratives to challenge the dominant tropes of drug genre photography.

More than anything, I wanted to represent Marie, Cheryl and Johnny as human beings – and show that their drug use didn’t define who they were, even though that’s how heroin users are usually depicted by documentary and news photographers.

The best way to do this, I realized, was to show them the photographs I’d selected and give them the opportunity to respond. I included their words with each photograph in the series.

‘Dark, seedy, secret worlds’

Before beginning my project, I had explored the work of some of the most influential drug genre photographers, and found that most of them have consistently represented heroin users as exotic, primitive and dangerous to society.

“There is a tendency in drug photography to attempt to make images of dark, seedy, secret worlds,” writes criminologist John Fitzgerald.

This can have the effect of “ othering ” the subjects – the idea that after looking at these kinds of images, viewers might look at drug users as outcasts.

Larry Clark’s 1971 photo work “ Tulsa ” is considered an exemplar of documentary photography. Many view the series, which depicts teenagers experimenting with drugs, sexuality and guns, as brutally honest and revealing.

Clark’s follow-up photo essay, “Teenage Lust,” published in 1983, also focused on drug users in a voyeuristic, unsettling and erotic way.

The problem with this approach is that it creates sensationalized images, which, in turn, influence the public’s thinking and policymakers’ decisions about how to treat drug users.

“For Clark the drug user is a modern primitive,” writes Fitzgerald. “Like the young boys who play with guns and explore their sexuality, Clark’s drug users plumb the depths of rapacious desire, so repressed and unexplored in the modern body. Clark’s lifework is to bring this primitive desire to light in a liberal artistic adventure.”

Clark wasn’t the only photographer to represent heroin users this way. Documentary photographer Eugene Richards’ 1994 book Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue focused on cocaine use in three inner-city neighborhoods. The book’s cover features an extreme close-up of a woman clenching a syringe between her teeth.

The image is arresting and also influenced the way many other photographers have depicted drug users to this day.

Photojournalists working for news agencies such as AP , Getty Images and The Denver Post have recently followed Richards’ example and composed images of drug users with syringes in their mouths. In most of these photos, the heroin users’ eyes are either partially or completely out of frame or hard to make out in detail.

It’s vital that photographers find more balanced ways of representing drug users, instead of reproducing the same types of stigmatizing images that have existed for decades.

Shocking images certainly provoke reactions. But it’s more important to offer context in order to spark discussions about solutions.

Hearing from the heroin users

In my own effort to produce and share balanced and humanizing images – and to reduce the possibility of misinterpretation and “othering” – I realized the images on their own couldn’t tell the full story. I needed a way to provide context for the viewer.

“The multitude of meanings in a photograph makes it risky, arguably even irresponsible, to trust raw images of marginalization, suffering, and addiction to an often judgmental public,” write Philippe Bourgois and Jeffrey Schonberg in their 2009 book Righteous Dopefiend . “Letting a picture speak its thousand words can results in a thousand deceptions.”

After selecting my final images, I showed them to Marie, Cheryl and Johnny. I wanted to know if they thought the photos accurately represented them, if they thought anything was missing and what they would have done differently if they had taken the photos themselves.

Many of their responses were positive. They thought that in most of the images, I’d accurately represented them. And they had important suggestions. Most of all, they wanted to be seen in the photos as more than just drug users.

I’ve included their most telling comments alongside each of the photos in this story.

A needle in my arm is only ten percent of who I am. The other parts are going to the park and playing, having fun outside and watching children play. Being as much a part of as I can be in the community. I’m not just some dirty, mistrusting, drug addict from the skid row.

I don’t have to be in alleys [injecting heroin] anymore, like I used to be. I’m in a safe environment, no risk of getting or transmitting any infections, and my health is taken care of.

I’m caring for my pet whom I’ve have taken on the bus…I’m not selfish…. I don’t just think of me and my addiction. That was me, on the bus, going to see my Mom. I was going overnight so I had to take my cat with me. There’s more to my life than addiction… Like my cat. Like my family. Like taking time out to remember where and who I truly am. And where I come from.

People looking at this photo might possibly see that I’m being cruel. Which is not what I want them to see. I wasn’t trying to hurt her. She looks very scared and sad there. She looks alone. And I don’t like that because she’s not. I wasn’t trying to hurt her. I wanted her to meet my mom.

People seeing this photo could think anything . They could think that I’m going to see a drug dealer, they could think basically whatever they want, but that’s not what it is. I was going to see my Mom. [I wish viewers could see] my face, the smile on my face that I’m happy to see her. The excitement that I had because it was the first time I had seen her in a while.

I look confused, maybe a little freaked out or something. I don’t like [the photo]. I wish it weren’t so close up. Maybe it’s a harsh truth, I don’t know.

People seeing this photo might see somebody who’s happy, somebody who isn’t so dark or depressed…somebody who’s carefree and playful, and likes to enjoy herself. I do that all the time. I’m always like that… With a smile on my face, I try to always be happy. Which is really hard sometimes but yeah… It’s me.

I would like it if maybe they’d let me comb my hair, instead of looking like a real hardcore junkie here. I didn’t realize my hair looked so bad when I take my shirt off.

The reason why I take my shirt off is because I muscle the dope, I don’t IV it, because the reason why I do the dope is different from why a lot of other people do it. They do it to get high, I do it to help with some pain issues I have. I don’t want people thinking, “You know, these guys are going in there taking our tax dollars and doing heroin and getting high, look at them. You know, they’re nothing but detriments to society.” Well, I’ll tell ya, it’s saving my life.

I have a love for animals, especially cats. I had a cat in my life for the last year-and-a-half…well, no, the last eight months. And the more time I spent with humans, the more I love my cat.

I’m not much on being a show off, that’s why I put [the Siberian tiger tattoo] on my back… It’s something I’ve always wanted to do … and I managed to do that.

In this photo I’m trying not to break the law and grab some bottles and cash them in. So I can basically eat and have food. What’s missing is the security guards who usually hassle me. And, they have no reason to because I’m not hurting or stealing from them.

I’m also helping the environment because 80 percent of these bottles end up going to the landfill or the garbage. It’s not good for our ecosystem.

At this point in my life, I feel like I could come home at night and look in the mirror and not feel guilt or shame for what I was doing out there. Because I’m not stealing from anybody or hurting anybody.

People looking at this photo will see a fella who looks very intense. He looks tired. He’s out trying to make an honest dollar. He’s not proud of what he’s doing. But he’s doing what he has to, in order to survive. At the point where I’m at in my life, I think it’s a 100 percent accurate description of where my life is at. You can see the weariness, the life, the trials and tribulations I’ve been through.

I used to go into the shops and shoplift. I shoplifted quite a bit of food from this shop to feed my drug addictions, and that’s one thing you don’t see in this picture right now. I came and stole from this place and yet, a year later, I’m welcome to come in that store because I made an immense change and do not steal in there now. I come in and buy food like any other individual, and it makes me so proud to be able to do that.

You can see the intenseness in my face. It looks like I’m thinking deep about something and it’s just a feeling of gratitude of being happy and being alive… I hope people get out of this photograph that it’s never too late. And what I’ve been through in my life. We always have a chance as long as we stay positive in the moment. Live in the moment.

These are some nice carvings. If you look close enough, done in jade. Very nice done little pieces and very expensive little pieces.

This photo represents a point in my life when I needed money to do dope. These were the things I would steal to feed my drug addiction. And they were small enough, and easy enough to steal that I would do it. And I had no problem doing it. I never once got caught stealing and grabbing these pieces of ornaments. I would go into the store and take about five minutes. Five minutes of work would keep me unsick for approximately two or three days.

People viewing this photo might see some young girl, downtown, in a back alley. Looks like it’s a rough alley. A young girl, maybe she’s strung out, or maybe she’s determined to find drugs or who knows what they see in this photo. They just see a young girl smiling and looking down the alley.

Yeah, it shows all of me. I just hope the people see me in this photo – that I’m a striving, struggling drug addict. That I’m trying to better my life.

I want to show the people that this place is where we get our injections for our heroin opiate program, just show them that we need these places so heroin addicts can get off the streets. Heroin can be contaminated with many different poisons out there that can severely give us infections, because they put hog dewormer in the heroin on the streets. The clinical heroin here, there’s no bad chemicals or poisons in the drug. It helps us through the day, takes our aches and pains away, everything that heroin used to do.

In other places of the world, they had this study and it’s helped them, that’s why they brought it to Canada, here to [British Columbia]. And for us, the people who are in it, we’re so lucky and should be so grateful to have such a great program.

I hope the people see through this documentary all the points, all the emotions and desires, needs, and wants that we need, that you can help us down the road be able to successfully show our governments that people need the extra bit of help because we can’t do it on our own.

We need for you people to see that we’re not stereotyped monsters. We’re people just like you, just with an addiction. Something that we do a little bit more than others… When you look at this, take it with a grain of salt, because it could be your own daughter, it could be your own son out there doing exactly what I’m doing, but they had the door closed.

A drug addict’s world is not just the drugs, it’s how they get them, what you gotta do to get them. Sex trade, you know. Stealing, killing, whatever it might take just to get that extra dollar to get that extra fix so you can feel numb for the rest of the day. Not necessarily it’s always that, but in my life, I just want you to know that I’m struggling and I need that extra help.

I think the people will see a young girl having a cigarette out in the rain, painting her fingernails, enjoying the weather. Really studying, “Oh, come on, get the last bit of that nail polish out of the bottle.” I am just on the outside in the rain. I’m content. I’m puffing on my cigarette.

Well, now people will see that I have a band aid on my hand. They might think she has a cut on her hand, that’s why she’s having difficulties painting her fingernails and getting that nail polish out of the jar.

I’m sure there’s hundreds of photos that could show my life different. But my life today is a recovering heroin addict. I’m 124 pounds. I used weigh 97 pounds. There’s so many good things, and positive ways of looking at my life. If a picture could show all that emotion in one? That would be great, but it won’t and that’s all that my voice could tell you.

I think that people see a girl looking in the mirror, looking in fear, like what is she doing with the needle in her neck, sticking in her neck, that’s a pretty dangerous site to be injecting. But that’s the reality of that picture. It’s me being all strung out on dope, trying to get that shot into me, and it’s filled with blood and I’m trying to plug it into my vein cause I need that drug that’s in there so I can get off and get high, numb whatever pain I’m going through in that moment.

I was all fucked up on drugs that day, yeah. It shows my emotion, my fear, my determination. [I wish the photo had] maybe a little bit more light… Just to show it’s hard to inject into your neck like that. Just to show the picture more. To see what kind of struggle it is to inject in your neck. And to show maybe just a little bit more emotion to the people just to show what and why I’m doing that to myself.

Postscript: depicting the lives of users

Throughout the project, I’d spoken with the subjects about the purpose of the photo essay – to challenge the stereotypes of drug genre photography and to help spread awareness about heroin-assisted treatment.

I often explained to them that their photos would likely be published on the Internet – that police, future employers and others could learn they are heroin users. Despite the risks, the three subjects reiterated that they wanted to take part in the project because they, too, wanted to tell others about heroin-assisted treatment.

I’d been told that after enrolling in the heroin-assisted treatment study, some participants had reconnected with family members, found stable housing and gotten jobs. I hoped that I’d be able to take photos of Marie, Cheryl and Johnny in these types of settings.

However, I quickly learned that this wouldn’t be easy. Two of the three subjects didn’t engage in many other activities beyond self-injecting at the Crosstown clinic three times a day. Outside the clinic, much of their time was spent acquiring and using drugs.

This meant the moments I was able to capture ended up being far less varied than I’d anticipated.

Still, there were revealing moments, like when I managed to photograph Marie traveled across the city by bus to try to find her mother. It was Thanksgiving and she hadn’t seen her mother in over two years. I thought these particular photos might help the viewer understand Marie in a new way: even if people weren’t able to fully understand the depth of Marie’s suffering or the roots of her addiction, everyone knows what it’s like to want to spend the holidays with loved ones.

The greatest challenge I faced was determining how to document two of the subjects’ ongoing drug use outside of the heroin-assisted treatment study. I simply couldn’t ignore it because it was a major part of their day-to-day lives. Marie and Cheryl told me that since the study was double-blind, they might not have been receiving the right medication – or high enough doses – to suppress their need to use other drugs. This doesn’t mean heroin-assisted treatment doesn’t work.

When the time came to choose the final photographs, I deliberately left out images that I suspected could be viewed as the most sensational or degrading.

My photo of Cheryl, lit by a candle and injecting drugs into her neck in front of a mirror in her apartment may not appear any less shocking than other drug genre photographers’ images of injection scenes.

However, Cheryl’s own words that accompany the photo provide critical context for the viewer. She explains that she was compelled to buy street drugs and inject into her neck – even though she knew the drugs could be contaminated and possibly kill her – because she was desperate to do whatever she could to feel well, even if this meant risking her life.

In order to see Cheryl as more than a drug user, the viewer needs to know this.

- Photography

- Documentary

- Media ethics

- Journalism ethics

- drug treatment

- Drug addiction

- Addiction treatment

- Documentary Photography

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 195,200 academics and researchers from 5,101 institutions.

Register now

This Magazine

Progressive politics, ideas & culture

PHOTO ESSAY: The faces behind Vancouver’s overdose crisis

Photojournalist aaron goodman provides an inside look at one woman's struggle with addiction on the west coast.

Aaron Goodman @aaronjourno

More information on the Outcasts Project can be found at outcastsproject.com .

Cheryl prepares to use drugs in her apartment in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

We need for you people to see that we’re not stereotyped monsters. We’re people just like you, just with an addiction. Something that we do a little bit more than others… When you look at this, take it with a grain of salt, because it could be your own daughter, it could be your own son out there doing exactly what I’m doing, but they had the door closed.

A drug addict’s world is not just the drugs, it’s how they get them, what you gotta’ do to get them. Sex trade, you know. Stealing, killing, whatever it might take just to get that extra dollar to get that extra fix so you can feel numb for the rest of the day. Not necessarily it’s always that, but in my life, I just want you to know that I’m struggling and I need that extra help.

Cheryl cries in the yard of a church where her father’s funeral was held.

I hope the people see through this [essay] all the points, all the emotions and desires, needs, and wants that we need, that you can help us down the road be able to successfully show our governments that people need the extra bit of help because we can’t do it on our own.

Cheryl self-injects her medication at Providence Health Care’s Crosstown Clinic in Vancouver.

I want to show the people that this place is where we get our injections for our heroin opiate program, just show them that we need these places so heroin addicts can get off the streets. Heroin can be contaminated with many different poisons out there that can severely give us infections, because they put hog dewormer in the heroin on the streets. The clinical heroin here, there’s no bad chemicals or poisons in the drug. It helps us through the day, takes our aches and pains away, everything that heroin used to do.

In other places of the world, they had this study and it’s helped them, that’s why they brought it to Canada, here to [British Columbia]. And for us, the people who are in it, we’re so lucky and should be so grateful to have such a great program.

Cheryl paints her nails prior to a court appearance for a sexual assault she experienced.

I’m sure there’s hundreds of photos that could show my life different. But my life today is a recovering heroin addict. I’m 124 pounds. I used to weigh 97 pounds. There’s so many good things, and positive ways of looking at my life. If a picture could show all that emotion in one? That would be great, but it won’t and that’s all that my voice could tell you.

Cheryl self-injects drugs in her apartment in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

I think that people see a girl looking in the mirror, looking in fear, like what is she doing with the needle in her neck, sticking in her neck, that’s a pretty dangerous site to be injecting. But that’s the reality of that picture. It’s me being all strung out on dope, trying to get that shot into me, and it’s filled with blood and I’m trying to plug it into my vein cause I need that drug that’s in there so I can get off and get high, numb whatever pain I’m going through in that moment.

I was all fucked up on drugs that day, yeah. It shows my emotion, my fear, my determination. [I wish the photo had] maybe a little bit more light… Just to show it’s hard to inject into your neck like that. Just to show the picture more. To see what kind of struggle it is to inject in your neck. And to show maybe just a little bit more emotion to the people just to show what and why I’m doing that to myself.

Cheryl returns to an alley in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside where she lived for several years.

People viewing this photo might see some young girl, downtown, in a back alley. Looks like it’s a rough alley. A young girl, maybe she’s strung out, or maybe she’s determined to find drugs or who knows what they see in this photo. They just see a young girl smiling and looking down the alley.

Yeah, it shows all of me. I just hope the people see me in this photo—that I’m a striving, struggling drug addict. That I’m trying to better my life.

Aaron Goodman is a journalist, researcher, and instructor. His work focuses on amplifying the voices and experiences of people affected by social injustices, human rights abuses, conflict, and genocide. You can follow him on Twitter: @aaronjourno.

‘Two Lives Lost to Heroin’: A Harrowing, Early Portrait of Addicts

Karen and John were the main subjects of a LIFE story on heroin addiction. Here Karen had her arms around John and his brother, Bro— also an addict—as they lay on a hotel bed.

Bill Eppridge The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Written By: Ben Cosgrove

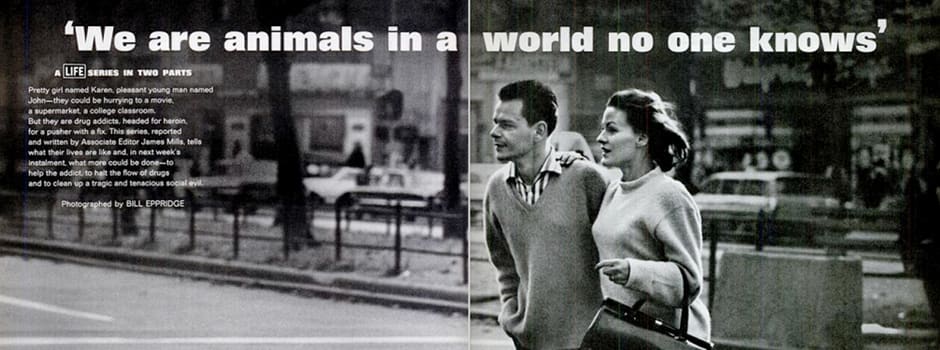

‘We are animals in a world no one knows’

In February 1965, LIFE magazine published an extraordinary photo essay on two New York City heroin addicts, John and Karen. Photographed by Bill Eppridge, the pictures and the accompanying article, reported and written by LIFE associate editor James Mills were part of a two-part series on narcotics in the United States. A sensitive, clear-eyed and harrowing chronicle of, as LIFE phrased it, “two lives lost to heroin,” Eppridge’s pictures shocked the magazine’s readers and brought the sordid, grim reality of addiction into countless American living rooms.

To this day, Eppridge’s photo essay remains among the most admired and, for some, among the most controversial that LIFE ever published. His pictures and Mills’ reporting, meanwhile, formed the basis for the 1971 movie, Panic in Needle Park , which starred Al Pacino and Kitty Winn as addicts whose lives spin inexorably out of control.

Here, LIFE.com presents Eppridge’s “Needle Park” photo essay in its entirety, as it appeared in LIFE a portrait of two young people who have become, as they themselves put it, “animals in a world no one knows.”

[See more of Bill Eppridge’s work.]

Karen and John were the main subjects of a LIFE story on heroin addiction. Here Karen had her arms around John and his brother, Bro— also an addict—as they lay on a hotel bed. Bill Eppridge The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Needle Park, LIFE magazine, Feb. 26, 1965

More Like This

A Joyful Thanksgiving and a “Marriage Experiment”

Pamper House: America As It Was Learning to Treat Itself

Wild and Frozen: Minnesota at Its Coldest and Most Remote

A Lone Star Fashion Show, 1939

The Moment When Sweaters Grew Up

The Logging Life: Gone Down the River

Subscribe to the life newsletter.

Travel back in time with treasured photos and stories, sent right to your inbox

LIFE's Classic Photo Essay That Shined a Harsh Light on Heroin Addiction

Bill Eppridge's iconic 1965 work documented the horrors of heroin addiction in New York City.

Updated October 2, 2014

Products are chosen independently by our editors. Purchases made through our links may earn us a commission.

"While there's Life, there's hope."

That was the original motto of LIFE Magazine, which after reforming under new ownership in 1936 would go on to document lives of people around the world—an unyielding look at the wondrous, the encouraging, and sometimes brutal realities of everyday life.

Opening with a shot of the two dressed up, strolling through the streets of New York City, they look like any other well-heeled couple out for a stroll. At the top of the page the couple's words tell a drastically different story: "We are animals in a world no one knows."

The essay documents the lives of Karen and Johnny as they cope with addiction and everything they must do to maintain their supply. Despite both coming from well-off families, Karen deals drugs and becomes a prostitute while Johnny resorts to stealing from cabs, eventually getting arrested for disorderly conduct.

While Johnny is in jail, Eppridge photographs a particularly powerful scene in a hotel room with Karen struggling to keep her dealer Billy alive after an overdose. After taking five tablets of the prescription drug Doriden, Billy mainlines a shot of heroin and nearly passes out. Karen spends two hours keeping Billy on his feet, shouting into his ear, doing anything to keep him awake:

Open your eyes, Billy. Try to wake up. You took too much stuff, Billy. Don't go to sleep–you might not wake up. You got to fight it Billy! Do you hear me, Billy? Billy. Do you hear me, Billy? You got to fight it. Billy? Billy?

After two hours Billy finally can stand on his own. Karen is pictured laying on the bed watching Billy smoke a cigarette to right himself. Knowing Billy will survive, she does a shot of heroin herself. While there's life, there's hope.

Bill Eppridge photographed Karen and Johnny for three months while reporting on their lives. He blended in so well amongst the addicts after awhile that he was stopped by the cops who wanted to know where he stole his camera.

I was sitting in the lobby of the hotel, waiting for her to come down, and I got a phone call. It was Karen, she said, “You’d better come up here, we got a problem.” Her dealer had overdosed. The guy could have died. It was a big dilemma; Should I call the police or should I photograph it? I asked Karen how she felt about it and she said she could bring him 'round. So I took her word for it and didn’t call 911. And she brought him around. I constantly faced situations that bordered on illegal. It was hard having to make these kinds of decisions, but I think I made the right ones most of the time.

(Editor's note: The original text of this article stated that Bill Eppridge lived with Karen and Johnny while photographing him. He did not. We regret the error.)

Prices were accurate at the time this article was published but may change over time.

Sign up for our newsletter.

Enter your email:

Thanks for signing up.

Editors Pick

Why you need to have a happy workforce

Public sector pay deals help drive up UK borrowing

Borrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Photo essay: Why Do We Take Drugs?

Christopher Jackson tours a fine new exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre about the many ways drugs impact our lives

After reading about the death of Liam Payne in Buenos Aries recently, one felt a sense of grim recognition. It was another story of a famous person with a bleak ending up, where the prime mover in the tragedy was drug addiction. This followed on from Matthew Perry ‘s sad death the previous year.

But you don’t have to look far in recent history to find others: Amy Winehouse , Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Michael Hutchence. It is a grim roll call of squandered talent. The trouble with talent is that it all too often distracts you from learning how to live. Know thyself, was the injunction above the entrance to Plato’s Academy.

Drugs certainly can prevent that process, but the Sainsbury Centre has embarked on a larger mission: to consider drugs from many angles and therefore to arrive at a deeper sense of what drugs have meant to the species recreationally, socially, politically, in healthcare, as well as artistically and even spiritually. The results are shown in a series of exhibitions, and also in an accompanying book which is both well-written and beautifully designed.

It was Gore Vidal who, in his usual lordly manner, said he’d tried each drug and rejected them all. He settled in the end on alcohol as his main source of recreation and it didn’t do him a huge amount of good, especially in his old age. But most people in their forties and fifties today will have dabbled in some form of drug, usually when too young to know precisely what kind of self they were supposedly meant to be experimenting with.

This has without question hugely contributed to the mental health crisis which we see all around us. It manifests all too often as an employability problem, but this is ordinarily a symptom of addiction and not a cause.

There is much in this exhibition to warn us off drugs, with heroin singled out as a particular disaster area. This was the tipple of the great Nick Cave , and he got through by the skin of his teeth to his present incarnation as a musical seer and global agony uncle.

Cave always made sure he was at his desk at 9am, and wrote some of the great songs of this or any age while in the clutches of this particularly brutal drug. The section of the exhibition called Heroin Falls makes it clear that the high-functioning heroin addict is likely to be an extremely rare phenomenon.

One such is Graham MacIndoe who chronicles his own addiction in photos of raw power. MacIndoe wasn’t robbed of agency by his addiction – or not entirely – and found that the drug made him focus with considerable obsessiveness on lighting his pictures.

My Addiction, Graham MacIndoe

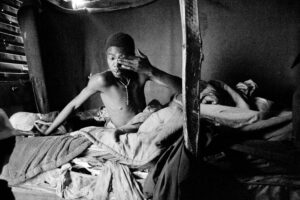

And yet heroin remains a grim topic whatever spin you put on it. That’s even more the case when you consider the current trend in South Africa for Nyaope, known as ‘poor man’s heroin’. This is highly addictive and can contain anything from detergent to rat poison or antiretroviral medications. Anybody who has been to Johannesburg knows that it can be hell on earth: and here’s why.

SOUTH AFRICA. Johannesburg. Thokoza. 2015. Thabang waking up in the early hours of the morning.

SOUTH AFRICA. Johannesburg. Katlehong. 2015. Bathing in Katlehong after a long day.

But the Sainsbury Centre frequently points out that drug use hasn’t always been this destructive. The message is that, as with anything in life, it helps to know what you’re doing. There still exist today peoples in South America with a positive relationship to Ayahuasca.

Richard Evans Schultes, The Cofan Family that met Schultes at Canejo, Rio Sucumbios, April 1942

Richard Evans Schultes, Cano Guacaya, Miritiparana, 1962

Richard Evans Scultes, Youth on the Paramo of San Antonio above the Valley of Subondoy, 1941

These pictures show another setting to drug exploration: we are in the great outdoors where drugs really originate. Quite simply, they grow in nature, and it is a relief to the viewer to be out of the urban setting where drug addiction so often goes badly wrong, into landscapes where the existence of drugs has a saner context.

As interesting as they are, they rather pale in comparison to some of the images of visionary art in this exhibition, the best of which is Robert Venosa’s Ayahuasca Dream , 1994.

Robert Venosa, Ayahuasca Dream, 1994

All one can say about this picture is that if this is how the world looks on ayahuasca, you’d be a bit crazy not to want to try some. This is why people take drugs: they sense that the external world might be an end effect of something larger and that drugs might be a way to move towards that cause.

Venosa’s picture, with its sense of a drama we can’t quite grasp conducted involving figures whose identity we only vaguely know will touch a chord with many. It is impossible to look at something of this scale and beauty, and feel that drugs can be of no benefit to humankind.

Most people suspect that their mind is operating at a very low percentage as they conduct the rote tasks which the modern world can sometimes seem to require of them. They know they’re capable of more.

I think it’s more than possible to do all that in a state of sobriety, and that route will be better in the vast majority of cases, simply because so many people lack the willpower not to fall into perennial addiction. Who can sort the real drug mentors in the Amazon jungle from the charlatans?

But the Sainsbury Centre has done a great thing by tackling this subject in such an encyclopaedic fashion to remind us that though we each have our inner Amy Winehouse where everything can go badly wrong, we also potentially have a sort of Sergeant Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band within as well – a new level to go to, whoever we are.

For more information go to: https://www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk/

Employability Portal

Useful links.

- Terms of Use

- Advertising Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Finito Education

Privacy Overview

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

I’m So Sick of Opioid Disaster Porn

I know that the photo essays showing the stark hell of addiction are trying to help. but they miss a huge part of the story—recovery..

Over the past couple of years, photojournalists have aimed their lenses at America’s most pressing public health emergency: the opioid overdose crisis. The March issue of Time did something the magazine had never done before: dedicate an entire issue to the work of one photographer, pre-eminent war photographer James Nachtwey, shooting one topic, the multitude of devastation wrought by America’s deadliest drug crisis in history, in black and white. Close-ups focus in on public injection and first responders bringing people back to life. Nachtwey’s images convey a battle being lost in his own country; the suffering, in this case, is at home.

As in his war photography, Nachtwey’s motivation to shoot “ The Opioid Diaries ” is genuine, even noble. In a tearful speech about the project at the Newseum in D.C., Nachtwey said it’s his and Time’s wish that the photo essay prompt “more effective ways of dealing with” the crisis among decision-makers. But in their laudable quest to document reality, projects like “The Opioid Diaries,” the New Yorker’s similarly themed “ Faces of an Epidemic ,” and even the Pulitzer Prize–winning “ Seven Days of Heroin ” from the Cincinnati Enquirer actually fail to capture it.

Rather, these glossy, often black-and-white images document a reductive slice of what the opioid crisis really is. Yes, there are funerals and overdoses, but they’re not the whole story. Nachtwey’s “Opioid Diaries” is described as a “visual record of a national emergency,” but by zooming in on only the most severe cases, shooting people at their lowest lows, and neglecting to capture even the possibility of recovery, he misses a whole side of the story. In the end, the portrait painted is so stark and dire that not only does it not reflect the current reality, it feels like a representation that could end up being harmful for people living with addiction who want to get better but feel helpless and hopeless.

Where’s the dignity afforded to other chronic illnesses? The choice to only show the dark side of addiction is like doing a spread on cancer but only showing bald people on their deathbeds, or commissioning a photo essay on HIV/AIDS that only features emaciated gay men. The respect media gives to other chronic illnesses is missing in these depictions of addiction.

And addiction is a chronic illness—one that tells a uniquely human story of psychological entanglement and contradictory motives. There are numerous theories of what causes drug addiction. But it tends to start (obviously) with liking the feelings that drugs produce (warmth, euphoria, belonging) or the erasure of other feelings (trauma, loneliness, anxiety)—usually both at once. After continued use, the body comes to depend on the drug to function, as life becomes more and more dysfunctional. Desire for the drug eventually becomes an act of survival. True addiction feels like being trapped in an escapable loop: You need the thing that’s destroying you.

The thing is, it is escapable. More often than not , there’s a third act to the story of addiction, one that hinges on personal growth and transformation. The latest national survey estimates that 22.35 million (or 1 in 10) adults in the U.S. have “resolved” an addiction. But public perception is skewed toward severe cases, thanks to narratives like the ones featured on A&E’s Intervention , where the addictions are always intense and require expensive rehab. The lives of millions of people who have recovered, some without any formal help whatsoever, are left out. That third act is largely absent from these projects.

And people who have overcome their addictions are an important part of the crisis. Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, best explained why in her recent piece for Scientific American: “Viewing [addiction] as a treatable medical problem from which people can and do recover is crucial for enabling a public-health–focused response that ensures access to effective treatments and lessens the stigma surrounding a condition that afflicts nearly 10 percent of Americans at some point in their lives.”

It’s also no coincidence that Time and the New Yorker decided to capture overdoses in black and white. In “Faces of an Epidemic,” text describing the crisis as a “mass-casualty event” is overlaid on a low-contrast, gray-washed looped video of a suburban Ohio street, producing a feeling of eerie horror. It’s a ghost’s vantage point. Nachtwey’s stark images in Time are even more brutal. Black-and-white photos are “visceral” and “evocative,” photojournalist Ryan Christopher Jones, whose work frequently appears in the New York Times, told me. “It’s tied to our cultural memory of how war and devastation have historically been visualized.” Jones says that depicting a modern drug crisis in black and white makes us feel like we’re looking at war. To me, it’s highly produced disaster porn.

To be fair, Nachtwey at least attempted to shoot recovery. The third act of “The Opioid Diaries” is titled “Aftermath, Resilience & Recovery.” But the first image in this section is of a 29-year-old woman experiencing withdrawal in a jail cell; a heart is etched next to the words “I miss my kids!!!” on the black concrete wall next to which she is shivering. (Withdrawal from heroin feels like having 24/7 goosebumps.) The next image is of a man, looking worn down, who volunteered for the jail’s “rehabilitation program”—whatever that is, if not a cruel redundancy. The third image is of another woman experiencing withdrawal in jail. Next is a man in handcuffs who is going back to jail after relapsing during drug court. I think you see the pattern (there are some photos that don’t involve jail—but those mostly show death).

Yes, it’s a sad truth that people are jailed rather than given medical help. But despite Nachtwey’s intention to show this to inspire “more effective” solutions, it seems likely that images like these instead further entrench the notion that addiction is a sin or crime and that jail is the right place for people with addiction. What the photo essays don’t capture is that when people with opioid addiction are released from jail, their risk of overdosing is astronomical thanks to their diminished tolerance. In fact, the prison conditions for people with addiction are so atrocious that they are currently being investigated as a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act , because life-saving medication that reduces the risk of overdose is being withheld. Sure, an argument could be made that showing addiction as a crime may motivate more humane fixes. But why not show what those more effective solutions would look like, too, at least to underscore the vast difference between them and incarceration?

Last October in Slate, I covered the increasing role that recovery activists are playing in the national dialogue about the overdose crisis. I went back to a few of those activists to ask what they thought about the photo essays. “They didn’t finish that article!” Garrett Hade, of Facing Addiction, told me about Time’s essay. “There’s a part after the criminal justice system. What happened to that person when they were released from probation and don’t have to go to court anymore? Did they get support? Are they employed?” Recovery activist Cortney Lovell told me that the “continued use of glorified drug paraphernalia in media only further stigmatizes an already vulnerable group of people.” For contrast, Lovell pointed to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “ Rx Awareness ” media campaign, which featured her in September 2017. Though not perfect, the CDC’s campaign didn’t feature disaster porn. Unlike the hopelessly dark, Requiem for a Dream –style images featured in major media outlets, the CDC featured the faces of healthy people who have moved beyond their addictions.

Similarly, Jones, who only shoots in color—because, as he put it, “we live in color”—recently photographed a number of people who have recovered from opioid addiction, including me, for a new photo essay in the New York Times that attempts to capture the third act of the story that is too often ignored. The project features close-ups taken by Jones next to words from Maia Szalavitz describing our different journeys, showing what our lives look like after addiction ends. Jones and Szalavitz teamed up out of mutual dissatisfaction over the year’s biggest opioid packages. Unique to their project is showcasing a diversity of pathways, bucking the status quo that prioritizes 12-step-style abstinence. The decision to use close-ups is also important: There’s no room for readers to distance themselves from the subjects; they’re forced to look us in the eye instead of at our scars.

This photo essay is similar to the Times’ “ Faces of HIV ” published in June 2013. Both show a variety of faces from different walks of life, people in suits at work, a black woman kissing her relative, a Native American woman in Minnesota who turned to her family’s spiritual tradition for help. The takeaway is powerful: Once thought to have a death sentence, people with HIV today are by and large living fruitful lives. The same is true today with addiction—and seeing it could make a world of difference.

Photo Essays: The Human Cost of Drug Policies in the Americas

Punished for Being Poor

Nayeli, 28, is an indigenous woman incarcerated in Cochabamba, Bolivia. She has suffered from sexual violence and has lived her entire life in poverty. Nayeli tells how abuse and poverty led to her involvement in the drug trade....

Life After Prison

“J”, 28, is a single mother of six. She agreed to carry drugs into a prison to feed her family, but changed her mind at the last second and gave the drugs to prison guards. She was arrested and sentenced to over five years...

Caught in a Vicious Cycle

Johanna, 31, grew up in a household where her parents sold drugs and was therefore exposed to the trade at a young age. When her mother was incarcerated and things got hard for her siblings, she agreed to carry of suitcase of...

Failed by the System

Sara, 50, fled her family at age 13 to escape sexual abuse at the hands of her uncle. With no education or opportunities, she became drug dependent and worked in the sex trade, and was eventually arrested for selling small...

Mother Behind Bars

Lidieth, a 45-year-old mother of four, says she was arrested for selling small quantities of crack and cocaine from her home in order to feed her family. Two of her adult children were implicated in the household business and...

How Would it be if We Had Opportunities?

Johana, an incarcerated woman from Colombia, tells how poverty and a need to support her children led her to sell drugs. For her, imprisonment only worsened her situation. Sentence: 6 years, 4 months for a drug offense. Johana...

I Am Not a Criminal

Ángela, 24 years old and mother of three, tells the story of the abuse she suffered from a young age, and how she became involved in the drug trade. Sentence: 6 years for bringing drugs into a prison. Ángela is 24 years old, a...

Kidnapped and Coerced

Many women who end up transporting drugs are co-opted by networks that use similar methods to those employed in human trafficking crimes. That is what happened to Liliana, a Venezuelan woman with two children who agreed to...

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Clark's follow-up photo essay, "Teenage Lust," published in 1983, also focused on drug users in a voyeuristic, unsettling and erotic way. ... A drug addict's world is not just the drugs ...

In 2014-15, Aaron Goodman documented three drug users participating in a study to assess longer-term opioid medication effectiveness—the first heroin-assisted treatment research of its kind in North America. The collected photos and reflections formed the Outcasts Project, which aims to humanize add ... PHOTO ESSAY: The faces behind ...

In February 1965, LIFE magazine published an extraordinary photo essay on two New York City heroin addicts, John and Karen. Photographed by Bill Eppridge, the pictures and the accompanying article, reported and written by LIFE associate editor James Mills were part of a two-part series on narcotics in the United States. A sensitive, clear-eyed ...

The photo essay, which ran along with an article written by Life Associate Editor James Mills, showed Karen and Johnny in the throes of addiction doing what they could to survive.

The opioid crisis is the worst addiction epidemic in American history. Drug overdoses kill more than 64,000 people per year, and the nation's life expectancy has fallen for two years in a row ...

The dark world of heroin addiction has been the subject of award-winning photography before — LIFE magazine photographer Bill Eppridge's gripping photo essay about two heroin addicts is as ...

The photo essay, which ran along with an article written by Life Associate Editor James Mills, showed the Karen and Johnny in the throes of addiction doing what they could to survive. ... After taking five tablets of the prescription drug Doriden, Billy mainlines a shot of heroin and nearly passes out. Karen spends two hours keeping Billy on ...

Photo essay: Why Do We Take Drugs? Christopher Jackson tours a fine new exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre about the many ways drugs impact our lives . After reading about the death of Liam Payne in Buenos Aries recently, one felt a sense of grim recognition. It was another story of a famous person with a bleak ending up, where the prime mover ...

This photo essay is similar to the Times' "Faces of HIV" published in June 2013. Both show a variety of faces from different walks of life, people in suits at work, a black woman kissing her ...

To shed light on this issue, WOLA has created a series of photo essays to show the human cost of current drug policies in the Americas. The essays tell the stories of six women, each providing a unique insight into the deeply troubling cycle of poverty, low-level involvement, imprisonment, and recidivism into which women are too often pushed.