An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Characteristics and Outcomes of School Social Work Services: A Scoping Review of Published Evidence 2000–June 2022

Estilla lightfoot, ruth berkowitz, samantha guz, cynthia franklin, diana m dinitto.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2023 Apr 9.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

School social workers are integral to the school mental health workforce and the leading social service providers in educational settings. In recent decades, school social work practice has been largely influenced by the multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) approach, ecological systems views, and the promotion of evidence-based practice. However, none of the existing school social work reviews have examined the latest characteristics and outcomes of school social work services. This scoping review analyzed and synthesized the focuses and functions of school social workers and the state-of-the-art social and mental/behavioral health services they provide. Findings showed that in the past two decades, school social workers in different parts of the world shared a common understanding of practice models and interests. Most school social work interventions and services targeted high-needs students to improve their social, mental/behavioral health, and academic outcomes, followed by primary and secondary prevention activities to promote school climate, school culture, teacher, student, and parent interactions, and parents’ wellbeing. The synthesis also supports the multiple roles of school social workers and their collaborative, cross-systems approach to serving students, families, and staff in education settings. Implications and directions for future school social work research are discussed.

Keywords: School social work, School mental health, MTSS, School social work practice model, Interdisciplinary collaboration

Introduction

This scoping review examines the literature on school social work services provided to address children, youth, and families’ mental/behavioral health and social service-related needs to help students thrive in educational contexts. School social work is a specialty of the social work profession that is growing rapidly worldwide (Huxtable, 2022 ). They are prominent mental/behavioral health professionals that play a crucial role in supporting students’ well-being and meeting their learning needs. Although the operational modes of school social work services vary, for instance, operating within an interdisciplinary team as part of the school service system, or through non-governmental agencies or collaboration between welfare agencies and the school system (Andersson et al., 2002 ; Chiu & Wong, 2002 ; Beck, 2017 ), the roles and activities of school social work are alike across different parts of the world (Allen-Meares et al., 2013 ; International Network for School Social Work, 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ). School social workers are known for their functions to evaluate students’ needs and provide interventions across the ecological systems to remove students’ learning barriers and promote healthy sociopsychological outcomes in the USA and internationally (Huxtable, 2022 ). In the past two decades, school social work literature placed great emphasis on evidence-based practice (Huxtable, 2013; 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ); however, more research is still needed in the continuous development of the school social work practice model and areas such as interventions, training, licensure, and interprofessional collaboration (Huxtable, 2022 ).

The school social work practice in the USA has great influence both domestically and overseas. Several core journals in the field (e.g., the International Journal of School Social Work, Children & Schools ) and numerous textbooks have been translated into different languages originated in the USA (Huxtable, 2022 ). In the USA, school social workers have been providing mental health-oriented services under the nationwide endorsement of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) (Avant & Lindsey, 2015 ; Barrett et al., 2020 ). In the past two decades, efforts at developing a school social work practice model recommended that school social workers have a master’s degree, embrace MTSS and use evidence-based practices (EBP) (Frey et al., 2012 ). Similar licensure requirements have been reported in other parts of the world (International Network for School Social Work, 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ), but the current state of research on MTSS and EBP applications in other countries is limited (Huxtable, 2022 ). Furthermore, although previous literature indicated more school social workers applied EBP to primary prevention, including trauma-informed care, social–emotional learning, and restorative justice programs in school mental health services (Crutchfield et al., 2020 ; Elswick et al., 2019 ; Gherardi, 2017 ), little research has been done to review and analyzed the legitimacy of the existing school social work practice model and its influence in the changing context of school social work services. The changing conditions and demands of social work services in schools require an update on the functions of school social workers and the efficacy of their state-of-the-art practices.

Previous Reviews on School Social Work Practice and Outcomes

Over the past twenty years, a few reviews of school social work services have been conducted. They include outcome reviews, systematic reviews, and one meta-analysis on interventions, but none have examined studies from a perspective that looks inclusively and comprehensively at evaluations of school social work services. Early and Vonk ( 2001 ), for example, reviewed and critiqued 21 controlled (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT] and quasi-experimental) outcome studies of school social work practice from a risk and resilience perspective and found that the interventions are overall effective in helping children and youth gain problem-solving skills and improve peer relations and intrapersonal functioning. However, the quality of the included studies was mixed, demographic information on students who received the intervention, such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and special education enrollment were missing, and the practices were less relevant to the guidelines in the school social work practice model (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2012 ). Later, Franklin et al. ( 2009 ) updated previous reviews by using meta-analytic techniques to synthesize the results of interventions delivered by social workers within schools. They found that these interventions had small to medium treatment effects for internalizing and externalizing problems but showed mixed results in academic or school-related outcomes. Franklin et al. ( 2009 ) approached the empirical evidence from an intervention lens and did not focus on the traits and characteristics of school social workers and their broad roles in implementing interventions; additionally, demographic information, symptoms, and conditions of those who received school social work services were lacking. Allen-Meares et al. ( 2013 ) built on Franklin and colleagues’ ( 2009 ) meta-analysis on school social work practice outcomes across nations by conducting a systematic review with a particular interest in identifying tier 1 and tier 2 (i.e., universal prevention and targeted early intervention) practices. School social workers reported services in a variety of areas (e.g., sexual health, aggression, school attendance, self-esteem, depression), and half of the included interventions were tier 1 (Allen-Meares et al., 2013 ). Although effect sizes were calculated (ranging from 0.01–2.75), the outcomes of the interventions were not articulated nor comparable across the 18 included studies due to the heterogeneity of metrics.

Therefore, previous reviews of school social work practice and its effectiveness addressed some aspects of these interventions and their outcomes but did not examine school social workers’ characteristics (e.g., school social workers’ credentials) or related functions (e.g., interdisciplinary collaboration with teachers and other support personnel, such as school counselors and psychologists). Further, various details of the psychosocial interventions (e.g., service type, program fidelity, target population, practice modality), and demographics, conditions, or symptoms of those who received the interventions provided by school social workers were under-researched from previous reviews. An updated review of the literature that includes these missing features and examines the influence of current school social work practice is needed.

Guiding Framework for the Scoping Review

The multi-tiered systems of support model allows school social workers to maximize their time and resources to support students’ needs accordingly by following a consecutive order of prevention. MTSS generally consists of three tiers of increasing levels of preventive and responsive behavioral and academic support that operate under the overarching principles of capacity-building, evidence-based practices, and data-driven decision-making (Kelly et al., 2010a ). Tier 1 interventions consist of whole-school/classroom initiatives (NASW, 2012 ), including universal positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS) (Clonan et al., 2007 ) and restorative justice practices (Lustick et al., 2020 ). Tier 2 consists of targeted small-group interventions meant to support students at risk of academic or behavioral difficulties who do not respond to Tier 1 interventions (National Association of Social Workers, 2012 ). Finally, tier 3 interventions are intensive individual interventions, including special education services, meant to support students who do not benefit sufficiently from Tier 1 or Tier 2 interventions.

The current school social work practice model in the USA (NASW, 2012 ) consists of three main aspects: (1) delivering evidence-based practices to address behavioral and mental health concerns; (2) fostering a positive school culture and climate that promotes excellence in learning and teaching; (3) enhancing the availability of resources to students within both the school and the local community. Similar expectations from job descriptions have been reported in other countries around the world (Huxtable, 2022 ).

Moreover, school social workers are specifically trained to practice using the ecological systems framework, which aims to connect different tiers of services from a person-in-environment perspective and to activate supports and bridge gaps between systems (Huxtable, 2022 ; Keller & Grumbach, 2022 ; SSWAA, n.d.). This means that school social workers approach problem-solving through systemic interactions, which allows them to provide timely interventions and activate resources at the individual, classroom, schoolwide, home, and community levels as needs demand.

Hence, the present scoping review explores and analyzes essential characteristics of school social workers and their practices that have been missed in previous reviews under a guiding framework that consists of the school social work practice model, MTSS, and an ecological systems perspective.

This scoping review built upon previous reviews and analyzed the current school social work practices while taking into account the characteristics of school social workers, different types of services they deliver, as well as the target populations they serve in schools. Seven overarching questions guided this review: (1) What are the study characteristics of the school social work outcome studies (e.g., countries of origin, journal information, quality, research design, fidelity control) in the past two decades? (2) What are the characteristics (e.g., demographics, conditions, symptoms) of those who received school social work interventions or services? (3) What are the overall measurements (e.g., reduction in depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], improvement in parent–child relationships, or school climate) reported in these studies? (4) What types of interventions and services were provided? (5) Who are the social work practitioners (i.e., collaborators/credential/licensure) delivering social work services in schools? (6) Does the use of school social work services support the promotion of preventive care within the MTSS? (7) What are the main outcomes of the diverse school social work interventions and services?

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first scoping review to examine these aspects of school social work practices under the guidance of the existing school social work practice model, MTSS, and an ecological systems perspective.

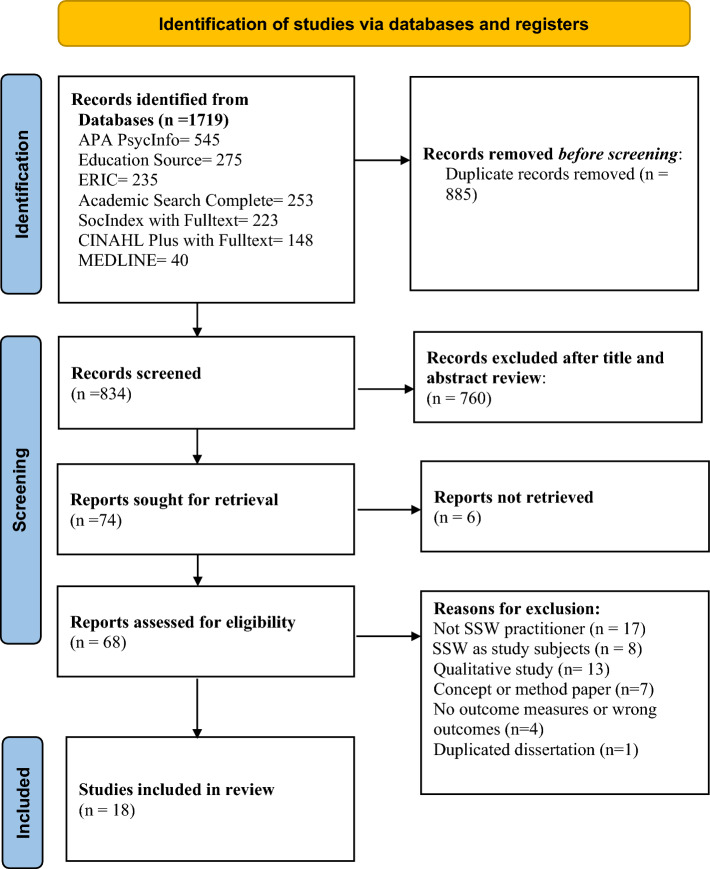

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension guidelines for completing a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018 ) were followed for planning, conducting, and reporting the results of this review. The PRISMA scoping review checklist includes 20 essential items and two optional items. Together with the 20 essential items, the optional two items related to critical appraisal of included sources of evidence were also followed to assure transparency, replication, and comprehensive reporting for scoping reviews.

Search Strategy

The studies included in this review were published between 2000 and June 2022. These studies describe the content, design, target population, target concerns, delivery methods, and outcomes of services, practices, and interventions conducted or co-led by school social workers. This time frame was selected since it coincides with the completion of the early review of characteristics of school social work outcomes studies (Early & Vonk, 2001 ); furthermore, scientific approaches and evidence-based practice were written in the education law for school-based services since the early 2000s in the USA, which greatly impacted school social work practice (Wilde, 2004 ), and was reflected in the trend of peer-reviewed research in school practice journals (Huxtable, 2022 ).

Following consultation with an academic librarian, the authors systematically searched relevant articles in seven academic databases (APA PsycINFO, Education Source, ERIC, Academic Search Complete, SocINDEX, CINAHL Plus, and MEDLINE) between January 2000 and June 2022. These databases were selected due to the relevance of the outcomes and the broad range of relevant disciplines they cover. When built-in search filters were available, the search included only peer-reviewed journal articles or dissertations written in English and published between 2000 and 2022. The search terms were adapted from previous review studies with a similar purpose (Franklin et al., 2009 ). The rationale for adapting the search terms from a previous meta-analysis (Franklin et al., 2009 ) was to collect outcomes studies and if feasible (pending on the quality of the outcome data and enough effect sizes available) to do a meta-analysis of outcomes. Each database was searched using the search terms: (“school social work*”) AND (“effective*” OR “outcome*” OR “evaluat*” OR “measure*”). The first author did the initial search and also manually searched reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional publications. All references of included studies were combined and deduplicated for screening after completion of the manual search.

Eligibility Criteria

The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used at all stages of the review process. Studies were included if they: (1) were original research studies, (2) were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals or were dissertations, (3) were published between 2000 and 2022, (4) described school social work services or identified school social workers as the practitioners, and (5) reported at least one outcome measure of the efficacy or effectiveness of social work services. Studies could be conducted in any country and were included for full-text review if they were published in English. The authors excluded: (1) qualitative studies, (2) method or conceptual papers, (3) interventions/services not led by school social workers, and (4) research papers that focused only on sample demographics (not on outcomes). Qualitative studies were excluded because though they often capture themes or ideas, experiences, and opinions, they rely on non-numeric data and do not quantify the outcomes of interventions, which is the focus of the present review. If some conditions of qualification were uncertain based on the review of the full text, verification emails were sent to the first author of the paper to confirm. Studies of school social workers as the sample population and those with non-accessible content were also excluded. If two or more articles (e.g., dissertation and journal articles) were identified with the same population and research aim, only the most recent journal publication was selected to avoid duplication. The protocol of the present scoping review can be retrieved from the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/4y6xp/?view_only=9a6b6b4ff0b84af09da1125e7de875fb .

A total of 1,619 records were initially identified. After removing duplicates, 834 remained. The first and the fourth author conducted title and abstract screening independently on Rayyan, an online platform for systematic reviews (Ouzzani et al., 2016 ). Another 760 records were removed from the title and abstract screening because they did not focus on school social work practice, were theory papers, or did not include any measures or outcomes, leaving 68 full-text articles to be screened for eligibility. Of these, 16 articles were selected for data analysis. An updated search conducted in June 2022 identified two additional studies. The combined searches resulted in a total of 18 articles that met the inclusion criteria. The first and the fourth author convened bi-weekly meetings to resolve disagreements on decisions. Reasons and number for exclusion at full-text review were reported in the reasons for exclusion in the PRISMA chart. The PRISMA literature search results are presented in Fig. 1 .

PRISMA Literature Search Record

Data Extraction

A data extraction template was created to aid in the review process. The information collected from each reference consists of three parts: publication information, program features, and practice characteristics and outcomes. Five references were randomly selected to pilot-test the template, and revisions were made accordingly. To assess the quality of the publication and determine the audiences these studies reached, information on the publications was gathered. The publication information included author names, publication year, country/region, publication type, journal name, impact factor, and the number of articles included. The journal information and impact factors came from the Journal Citation Reports generated by Clarivate Analytics Web of Science (n.d.). An impact factor rating is a proxy for the relative influence of a journal in academia and is computed by dividing the number of citations for all articles by the total number of articles published in the two previous years (Garfield, 2006 ). Publication information is presented in Table 1 . Program name, targeted population, sample size, demographics, targeted issues, treatment characteristics, MTSS level, and main findings (i.e., outcomes) are included in Table 2 . Finally, intervention features consisting of study aim and design, manualization, practitioners’ credential, fidelity control, type of intervention, quality assessment, and outcome measurement are presented in Table 3 . Tables 2 and 3 are published as open access for review and downloaded in the Texas Data Repository (Ding, 2023 ).

Journals Reviewed, Impact Factor, and Number of Articles Selected for Review

* The definition of impact factor (IF) is from Journal Citation Reports produced by Clarivate Analytics. IF is calculated based on a two-year period by dividing the number of citations in the JCR year by the total number of articles published in the two previous years

General Information on the Included School Social Work Practices

Note. Bx behavior, ed education, yo years old, yr = year. tx treatment, w with, T treatment group, C control group, INT intervention, CON control, FRPL Free/Reduced prices lunch, IEP Individualized education program, CBT cognitive behavior therapy, BST Behavior skill training, HADS-A Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Characteristics of the Included Research Studies

Note. NR Not reported, NA Not applicable, h hours, tx treatment, wk week, SSW School social work, IOA Interobserver agreement, SS single subject, AB baseline and intervention, SBC Student behavior checklist, GPA Grade point average, SRAS-C-R School refusal assessment scale-children-revised, SRAS-P-R School refusal assessment scale-parent-revised, CD-RISC Connor-davidson resilience scale, FAD-GFS McMaster family assessment device general functioning scale, PSS Perceived stress scale, PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder, PC-PTSD Primary care post-traumatic stress disorder screen, RYDM Resilience youth development module, CHKS The California healthy kids survey, CPSS Child PTSD symptom scale, CDI Children depression inventory, TRF Teacher report form, BRIC Behavior rating index for children, HPC Problem checklist, BERS The behavioral and emotional rating scale, SSRS The social skills rating system. SSP The school success profile, BDI Beck depression inventory. DAS Dysfunctional attitudes scale, PGIS-II Personal growth initiative scale II, GHQ-12 Chinese general health questionnaire-12, Q-LES-Q-18 Abbreviated quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire, PSI Parenting stress index- parent domain, PSOC Parenting sense of competence scale- efficacy subscale

The 18 extracted records were coded based on the data extraction sheet. The first and the fourth authors acted as the first and the second coder for the review. An inter-rater reliability of 98.29% was reached after the two coders independently completed the coding process.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the eligible studies (e.g., methodological rigor, intervention consistency) was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Evans et al., 2015 ). Specifically, each included study was assessed for selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, dropouts or withdrawals, intervention integrity, and analyses. The first and fourth authors rated each category independently, aggregated ratings, and came to a consensus to assign an overall quality rating of strong, moderate, or weak for each of the 18 studies.

Data Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of the interventions, study purposes, methods, and measurements of the selected studies, and the lack of outcome data to calculate effect sizes, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Hence, the authors emphasized the scoping nature of this review, data were narratively synthesized, and descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentage, mode, minimum, maximum, and range) were reported. Characteristics of included studies include topics, settings, participants, practice information (e.g., type of services, practitioner credential, MTSS modality, and other characteristics), and program efficacy. Within each reported category of interest, consistency and differences regarding the selected studies were synthesized. Unique features and reasons for some particular results were explained using analysis evidence according to the characteristics of the study.

Overall Description of Included Studies

Of the 18 included studies, 16 were reported in articles that appeared in 11 different peer-reviewed journals, and two were dissertations (Magnano, 2009 ; Phillips, 2004 ). Information on each of the 11 journals was hand-searched to insure thoroughness. Of the 11 journals, seven were in the field of social work, with one journal covering social work as it relates to public health; one was a school psychology journal; one a medical journal covering pediatric psychiatry; and one journal focused on child, adolescent, and family psychology. The most frequently appearing journal was Children & Schools , a quarterly journal covering direct social work services for children (Oxford University Press, 2022 ). An impact factor (IF) was identified for six of the 11 journals. Of the six journals with an IF rating, four were social work journals. The IF of journals in which the included studies were published ranged from 1.128 to 12.113 (Clarivate Analytics, n.d.). Of the 18 studies, 5 studies (28%) were rated as methodologically strong, 8 studies were rated as moderate (44%), and 5 studies were rated as weak (28%).

The studies were conducted in five different geographical areas of the world. One study was conducted in the Middle East (5.56%), one in north Africa (5.56%), one in Eastern Europe (5.56%), two in East Asia (11.11%), and the rest (13 studies) in the USA (72.22%).

Research Design and Fidelity Control

Concerning research design, most included studies used a pre-posttest design without a comparison group ( n = 10, 61.11%), one used a single case baseline intervention design (5.56%), six (33.33%) used a quasi-experimental design, and one (5.56%) used an experimental design. For the control or comparison group, the experimental design study and four of the six quasi-experimental design studies used a waitlist or no treatment control/comparison group; one quasi-experimental design study offered delayed treatment, and one quasi-experimental design study offered treatment as usual. Nine studies (50%) reported that training was provided to the practitioners prior to the study to preserve fidelity of the intervention, four studies (22.22%) reported offering both training and ongoing supervision to the practitioners, and one study (5.56%) reported providing supervision only.

Study Sample Characteristics

Across the 18 included studies, the total number of participants was 1,194. In three studies, the participant group (sample) was no more than ten, while in nine studies, the intervention group was more than 40. Overall, there was a balance in terms of students’ sex, with boys comprising an average of 55.51% of the total participants in all studies. There were slightly more studies of middle school or high school students ( n = 8) than pre-K or elementary school students ( n = 5). Across the eight studies that reported students’ race or ethnicity, 13.33% of the students were Black, 18.41% were White, 54.60% were Latinx, 12.38% were Asian, and 1.27% were categorized as “other.” Although the studies reviewed were not restricted to the USA, the large number of Latinx participants from two studies (Acuna et al., 2018 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ) might have skewed the overall proportions of the race/ethnicity composition of the study samples. As an indicator of socioeconomic status, eight studies reported information on free/reduced-price lunches (FRPL). The percentage of students who received interventions that qualified for FRPL varied from 53.3 to 87.9%. Five studies reported the percentage of students enrolled in an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or special education, ranging from 15.4% to 100%.

Variation in School Social Work Services

The services carried out or co-led by school social workers varied greatly. They included services focused on students’ mental health/behavioral health; academic performance; school environment; student development and functioning in school, classroom, and home settings; and parenting. More specifically, these interventions targeted students’ depression and anxiety (Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Phillips, 2004 ; Wong et al., 2018a ), social, emotional, and behavioral skills development (Acuna et al., 2018 ;Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Ervin et al., 2018 ; Magnano, 2009 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ), school refusal and truancy (Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ; Newsome et al., 2008 ; Young et al., 2020 ), trauma/PTSD prevention, community violence, and students’ resilience (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ;Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Wong et al., 2018a ), homework completion and grade-point average improvement (Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Magnano, 2009 ; Newsomoe, 2005 ), parental stress (Fein et al., 2021 ; Wong et al., 2018b ), family functioning (Fein et al., 2021 ), and parenting competence and resilience (Wong et al., 2018b ). All of the studies were school-based (100%), and the most common setting for providing school social work services was public schools.

Diverse Interventions to Promote Psychosocial Outcomes

Services can be grouped into six categories: evidence-based programs or curriculums (EBP), general school social work services, case management, short-term psychosocial interventions, long-term psychosocial intervention, and pilot program. Seven studies (38.89%) were EBPs, and four (57.14%) of the seven EPBs were fully manualized (Acuna et al., 2018 ; Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ; Fein et al., 2021 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ). Two EBPs (28.57%) were partially manualized (Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Kelly & Bluestone-Miller, 2009 ), one did not report on manualization (Chupp & Boes, 2012 ), and one is a pilot study trying to build the program’s evidence base (Young et al., 2020 ). The second-largest category was short-term psychosocial interventions reported in six (33.33%) of the studies; they included cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), and social/emotional skills training. One study reported on a long-term psychosocial intervention (Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ), and one was a case management program (Magnano, 2009 ). Two studies included general school social work services (e.g., one-on-one interventions with children and youth, group counseling, phone calls, official and informal conversations with teachers and parents, check-ins with students at school, and collaboration with outside agencies) (Newsome et al., 2008 ; Sadzaglishvili et al., 2020 ).

Program Population

Of the 18 interventions, seven (38.89%) involved students only (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ;Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Ervin et al., 2018 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Phillips, 2004 ; Wong et al., 2018a ; Young et al., 2020 ). One program (5.56%) worked with parent–child dyads (Acuna et al., 2018 ), and two (11.11%) worked directly with students’ parents (Fein et al., 2021 ; Wong et al., 2018b ). Four interventions (22.22%) involved students, parents, and teachers (Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Magnano, 2009 ), two (11.11%) were with students and their teachers (Kelly & Bluestone-Miller, 2009 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ), and two (11.11%) were more wholistically targeted at students, parents, and their families as service units (Newsome et al., 2008 ; Sadzaglishvili et al., 2020 ).

Practitioners and Credentials

School social workers often collaborate with school counselors, psychologists, and schoolteachers in their daily practice. As for the titles and credentials of those providing the interventions, twelve interventions were conducted solely by school social workers (Acuna et al., 2018 ; Fein et al., 2021 ; Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Kelly & Bluestone-Miller, 2009 ; Magnano, 2009 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Newsome et al., 2008 ; Phillips et al., 2004 ; Sadzaglishvili et al., 2020 ; Wong et al., 2018a , 2018b ). Four social service programs were co-led by school social workers, school counselors and school psychologists (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ; Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ; Young et al., 2020 ). School social workers and schoolteachers collaborated in two interventions (Ervin et al., 2018 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ).

The most common credential of school social workers in the included studies was master’s-level licensed school social worker/trainee, which accounted for 62.50% of the studies (Acuna et al., 2018 ; Fein et al., 2021 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Phillips, 2004 ). Two studies did not specify level of education but noted that the practitioners’ credential was licensed school social worker (Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Wong et al., 2018a ). One intervention was conducted by both master’s and bachelor’s level social work trainees; however, the first author confirmed that they were all registered school social workers with the Hong Kong Social Work Registration Board (Wong et al., 2018b ).

Services by Tier

The predominant level of school social work services was tier 2 interventions (55.56%), with 10 interventions or services offered by school social workers falling into this category (Acuna et al., 2018 ; Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ; Ervin et al., 2018 ; Fein et al., 2021 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Phillips, 2004 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ; Wong et al., 2018a , 2018b ). The second largest category was tier 1 interventions, with five studies (27.78%) falling into this category (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ;Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Kelly & Bluestone-Miller, 2009 ; Sadzaglishvili et al., 2020 ). Only three (16.67%) were tier 3 services (Magnano, 2009 ; Newsome et al., 2008 ; Young et al., 2020 ).

Intervention Modality and Duration under MTSS

Most services ( n = 15, 83.33%) were small-group based or classroom-wide interventions (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ; Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ; Ervin et al., 2018 ; Fein et al., 2021 ; Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ; Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Kelly & Bluestone-Miller, 2009 ; Newsome, 2005 ; Phillips, 2004 ; Sadzaglishvili et al., 2020 ; Thompson & Webber, 2010 ; Wong et al., 2018a , 2018b ). One tier 2 intervention was carried out in both individual and group format (Acuna et al., 2018 ). Of the three tier 3 intervention studies, one reported using case management to serve individual students (Magnano, 2009 ), and two included both individual intervention, group counseling, and case management (Newsom et al., 2008 ; Young et al., 2020 ).

Intervention length and frequency varied substantially across studies. Services were designed to last from 6 weeks to more than 13 months. There were as short as a 5- to 10-min student–school social worker conferences (Thompson & Webber, 2010 ), or as long as a three-hour cognitive behavioral group therapy session (Wong et al., 2018b ).

Social Behavioral and Academic Outcomes

Most of the interventions focused on improving students’ social, behavioral, and academic outcomes, including child behavior correction/reinforcement, social–emotional learning (SEL), school attendance, grades, and learning attitudes. Ervin and colleagues ( 2018 ) implemented a short-term psychosocial intervention to reduce students’ disruptive behaviors, and Magnano ( 2009 ) used intensive case management to manage students’ antisocial and aggressive behaviors. Both interventions were found to be effective, i.e., there were statistically significant improvements at the end of treatment, with Ervin et al. ( 2018 ) reporting a large effect size using Cohen’s d. The SEL programs were designed to foster students’ resilience, promote self-esteem, respect, empathy, and social support, and teach negotiation, conflict resolution, anger management, and goal setting at a whole-school or whole-class level (Al-Rasheed et al., 2021 ; Chupp & Boes, 2012 ; Ijadi-Maghsooodi et al., 2017 ; Newsome, 2005 ). Students in all SEL interventions showed significant improvement at the end of treatment, and one study reported medium to small effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for problem-solving and overall internal assets, such as empathy, self-efficacy, problem-solving, and self-awareness (Ijadi-Maghsooodi et al., 2017 ).

Four studies measured the intervention’s impact on students’ academic performance. Magnano and colleagues ( 2009 ) reported that at the completion of the school social work case management intervention, academic skills were improved among both the intervention group students and the cross-over (control) group students who received the intervention at a later time. One study specifically addressed students’ school refusal behaviors and attitudes and found improvement in the treatment group at posttest and six-month follow-up (Elsherbiny et al., 2017 ). Two studies that addressed students’ absenteeism and truancy exhibited efficacy. School social work services significantly reduced risk factors related to truant behaviors (Newsome et al., 2008 ), and attendance increased post-program participation and was maintained after one, two, and three months (Young et al., 2020 ).

Students’ Psychological Distress

The studies that addressed students’ mental health focused on psychological distress, especially adolescents’ depression and anxiety. In three studies, school social workers conducted short-term psychosocial interventions, all using group-based CBT (Kataoka et al., 2003 ; Phillips, 2004 ; Wong et al., 2018a ). Kataoka and colleagues ( 2003 ) reported that bilingual, bicultural school social workers delivered group CBT in Spanish to help immigrant students cope with depressive symptoms due to violence exposure. Similarly, Wong and colleagues ( 2018a ) delivered group CBT in Chinese schools using their native language to address teenagers’ anxiety disorders. In the Kataoka et al. ( 2003 ) study, all student participants were reported to have made improvements at the end of the intervention, although there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention group and waitlisted comparison group. Phillips ( 2004 ) reported an eta-squared of 0.148 for cognitive-behavioral social skills training, indicating a small treatment effect. One study used a resilience classroom curriculum to relieve trauma exposure and observed lower odds of positive PTSD scores at posttest, but the change was not statistically significant (Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2017 ).

School Climate and School Culture

Regarding school social workers’ interest in school climate and school culture, Kelly and Bluestone-Miller ( 2009 ) and Sadzaglishvili and colleagues ( 2020 ) specifically focused on creating a positive learning environment and promoting healthy school culture and class climate. Kelly and Bluestone-Miller ( 2009 ) used Working on What Works (WOWW), a program grounded in the SFBT approach to intervene in a natural classroom setting to build respectful learning. Students were allowed to choose how to respond to expectations regarding their classroom performance (e.g., students list the concrete small goals to work upon in order to create a better learning environment), and teachers were coached to facilitate, ask the right questions, and provide encouragement and appropriate timely feedback. Sadzaglishvili and colleagues ( 2020 ) used intensive school social work services (e.g., case management, task-centered practice, advocacy, etc.) to support students’ learning, whole-person development, and improve school culture. At the end of the services, both studies reported a more positive school and class climate that benefited students’ behaviors and performance at school.

Teacher, Parent, and Student Interaction

Four studies addressed interactions among teachers, parents, and students to achieve desired outcomes. For instance, two studies provided a mesosystem intervention (e.g., a parent’s meeting with the teacher at the public school the child attended, which encompasses both the home and school settings). Acuna and colleagues ( 2018 ) provided a school-based parent–child interaction intervention to improve children’s behaviors at school and home, boost attendance, and improve academic outcomes. Similarly, Thompson and Webber ( 2010 ) intervened in the teacher–student relationship to realign students’ and teachers’ perceptions of school and classroom norms and improve students’ behaviors. Additionally, two interventions targeted the exosystem (e.g., positive environmental change to improve students’ stability, in order to promote school behaviors and academic performance). Kelly and Bluestone-Miller ( 2009 ) modeled solution-focused approaches as a philosophy undergirding classroom interactions between teachers and students. The positive learning environment further improved students’ class performance. Magnano and colleagues ( 2009 ) used a case management model by linking parents, teachers, and outside school resources to increase students’ support and achieve improvements in academic skills and children’s externalizing behaviors.

Parents’ Wellbeing

Most school counselors or school psychologists focus solely on serving students, while school social workers may also serve students’ parents. Two studies reported working directly and only with parents to improve parents’ psychological outcomes (Fein et al., 2021 ; Wong et al., 2018b ). Fein and colleagues ( 2021 ) reported a school-based trauma-informed resilience curriculum specifically adapted for school social workers to deliver to racial/ethnic minority urban parents of children attending public schools. At curriculum completion, parents’ overall resilience improved, but significance was attained in only one resilience item (“I am able to adapt when changes occur”) with a small effect size using Cohen’s d. Wong et al. ( 2018b ) studied school-based culturally attuned group-based CBT for parents of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); significantly greater improvements in the CBT parent group were found in distress symptoms, quality of life, parenting stress, competence, and dysfunctional beliefs post-intervention and at three-month follow-up .

This scoping review examined school social work practice by systematically analyzing the services school social workers delivered based on 18 outcome studies published between 2000 and 2022. The programs, interventions, or services studied were conducted by school social workers in five different countries/regions. These studies captured the essence of school social workers’ roles in mental health/behavioral health and social services in education settings provided to children, youth, families, and schoolteachers, and the evidence on practice outcomes/efficacy was presented.

Although using EBP, promoting a healthy school climate and culture, and maximizing community resources are important aspects of the existing school social work practice model in the USA (NASW, 2012 ), this review revealed and validated that school social workers in other countries used similar practices and shared a common understanding of what benefits the students, families, and the schools they serve (Huxtable, 2022 ). The findings also support the broad roles of school social workers and the collaborative ways they provide social and mental health services in schools. The review discussed school social workers’ functions in (1) helping children, youth, families, and teachers address mental health and behavioral health problems, (2) improving social–emotional learning, (3) promoting a positive learning environment, and (4) maximizing students’ and families’ access to school and community resources. Furthermore, although previous researchers argued that the lack of clarity about school social worker’s roles contributed to confusion and underutilization of school social work services (Altshuler & Webb, 2009 ; Kelly et al., 2010a ), this study revealed that in the past two decades, school social workers are fulfilling their roles as mental/behavioral health providers and case managers, guided by a multi-tiered, ecological systems approach. For example, in more than 80% of the studies, the services provided were preventive group work at tier 1 or 2 levels and operated from a systems perspective. Additionally, the findings suggest that while school social workers often provide services at the individual level, they frequently work across systems and intervene at meso- and exo-systems levels to attain positive improvements for individual students and families.

Evidence-based School Social Work Practice and MTSS

The present review supported school social workers’ use of evidence-based programs and valid psychosocial interventions such as CBT, SFBT, and social–emotional learning to foster a positive learning environment and meet students’ needs. Most of the included EBPs (85.71%) were either fully or partially manualized, and findings from the current review added evidence to sustain the common elements of general school social work practice, such as doing case management, one-on-one individual and group counseling, collaborations with teachers, parents, and community agencies. One pilot study examined the effectiveness of a school social worker-developed program (Young et al., 2020 ), which provided a helpful example for future research practice collaboration to build evidence base for school social work practice. However, although school social workers often work with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) student populations facing multiple risk factors, demographic information on race/ethnicity, special education enrollment, and socioeconomic status were missing in many included studies, which obstructed examination of the degree of match between the target population’s needs and evidence-based services or interventions provided.

Previous school social work national surveys conducted in the USA (Kelly et al., 2010a , 2015 ) found a discrepancy between the actual and ideal time expense on tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3 school social work activities. Even though school social workers would like to spend most of their time on primary prevention, they actually spent twice their time on secondary and tertiary prevention than on primary prevention (Kelly et al., 2010a ). However, the present review found that most interventions or evidence-based programs conducted by school social workers were tier 1 and tier 2, especially tier 2 targeted interventions delivered in a group modality. This discrepancy could be due to the focus of this review’s limited services to those provided by professionals with a school social worker title/credential both in the USA and internationally, and tier 2 and 3 activities were grouped together as one category called secondary and tertiary prevention in the school social work survey (Kelly et al., 2010a ). Our review highlights that tier 2 preventive interventions are a significant offering in school social worker-led, school-based mental health practice. Unlike tier 1 interventions that are designed to promote protective factors and prevent potential threats for all students, or intensive tier 3 interventions that demand tremendous amounts of time and energy from practitioners and often involve community agencies (Eber et al., 2002 ), tier 2 interventions are targeted to groups of students exhibiting certain risk factors and are more feasible and flexible in addressing their academic and behavioral needs. Moreover, considering the discrepancy between the high demand for services on campuses and the limited number of school social workers, using group-based tier 2 interventions that have been rigorously examined can potentially relieve practitioners’ caseload burdens while targeting students’ needs more effectively and efficiently.

School Social Work Credential

Recent research on school social workers’ practice choices showed that school social workers who endorsed primary prevention in MTSS and ecologically informed practice are more likely to have a graduate degree, be regulated by certification standards, and have less than ten years of work experience (Thompson et al., 2019 ). Globally, although data are limited, having a bachelor's or master’s degree to practice school social work has been reported in countries in North America, Europe, and the Middle East (Huxtable, 2022 ). Even though all practitioners in the present review held the title of “school social worker,” and the majority had a master’s degree, we suggest future research to evaluate school social work practitioners’ credentials by reporting their education, certificate/licensure status, and years of work experience in the education system, as these factors may be essential in understanding school social workers’ functioning.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

School social workers are an integral part of the school mental health workforce in education settings and often work in interdisciplinary teams that include schoolteachers, administrators, school counselors, and school psychologists (Huxtable, 2022 ). This scoping review found that one-third of interventions school social workers conducted were either co-led or delivered in collaboration with school counselors, school psychologists, or schoolteachers. Future research examining characteristics and outcomes of school social work practice should consider school social workers’ efforts in grounding themselves in ecological systems by working on interdisciplinary teams to address parent–child interactions, realign teacher–student classroom perceptions, or student–teacher–classroom culture to improve students’ mental health and promote better school performance.

Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

A scoping review is a valuable method for exploring a field that has not yet been extensively reviewed or is heterogeneous. Thus, a scoping review was chosen as the research method to examine school social work practice outcomes for this study. Although scoping reviews are generally considered rigorous, transparent, and replicable, the present study has several limitations. First, only published dissertations and journal articles published between 2000 and 2022 that were included in the seven aforementioned databases were reviewed. Government reports and other gray literature excluded from the present review might generate more results requiring critical evaluation and discussion. Second, although school social work practice is ecological system-centered, all studies analyzed in the present scoping review were school-based programs. The search terms did not include possible alternative settings. More extensive searches might identify additional results by specifying home or community settings. Third, this paper focused on the outcomes and efficacy of the most current school social work practices so that qualitative studies or studies that focus on practitioners’ demographics were excluded even though they might provide additional information on the characteristics of social workers. Last, evidence to support school social work interventions was based primarily on pre-posttest designs without the use of a control group, and some of the identified evidence-based programs or brief psychosocial interventions lacked sufficient information on participants’ characteristics (e.g., demographics, changes in means in outcomes), which are important in calculating practice effect sizes and potential moderators for meta-analysis to examine school social workers’ roles and effectiveness in carrying out these interventions.

The present scoping review found significant variation in school social work services in the US and other countries where school social work services have been studied. Social workers are a significant part of the mental health and social services workforce. Using schools as a natural hub, school social workers offer primary preventive groups or early interventions to students, parents, and staff. Their interests include but are not restricted to social behavioral and academic outcomes; psychological distress; school climate and culture; teacher, parent, and student interactions; and parental wellbeing. Future school mental health researchers who are interested in the role of school social work services in helping children, youth, and families should consider the changing education landscape and the response to intervention after the COVID-19 pandemic/endemic (Capp et al., 2021 ; Kelly et al., 2021 ; Watson et al., 2022 ). Researchers are also encouraged to collaborate with school social work practitioners to identify early mental health risk factors, recognize appropriate tier 2 EBPs, or pilot-test well-designed programs to increase students’ success.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the scoping review.

- Acuña MA, Martinez JI. Pilot evaluation of the back to basics parenting training in urban schools. School Social Work Journal. 2018;42(2):39–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen-Meares P, Montgomery KL, Kim JS. School-based social work interventions: A cross-national systematic review. Social Work. 2013;58(3):253–262. doi: 10.1093/sw/swt022. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Al-Rasheed, M. (2021). Resilience-based intervention for youth: An initial investigation of school social work program in Kuwait. International Social Work , 00208728211018729.

- Altshuler SJ, Webb JR. School social work: Increasing the legitimacy of the profession. Children and Schools. 2009;31:207–218. doi: 10.1093/cs/31.4.207. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson G, Pösö P, Väisänen E, Wallin A. School social work in Finland and other Nordic countries: Cooperative professionalism in schools. In: Huxtable M, Blyth E, editors. School social work worldwide. NASW Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Avant DW, Lindsey BC. School social workers as response to intervention change champions. Advances in Social Work. 2015;16(2):276–291. doi: 10.18060/16428. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett S., Eber L., Weist M. (2020). Advancing education effectiveness: Interconnecting school mental health and school-wide positive behavior support. OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports.

- Beck K. The diversity of school social work in Germany: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of School Social Work. 2017;2(1):1. doi: 10.4148/2161-4148.1021. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capp G, Watson K, Astor RA, Kelly MS, Benbenishty R. School social worker voice during COVID-19 school disruptions: A national qualitative analysis. Children and Schools. 2021;43(2):79–88. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdab007. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chiu S, Wong V. School social work in Hong Kong: Constraints and challenges for the special administrative region. In: Huxtable M, Blyth E, editors. School social work worldwide. NASW Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chupp AI, Boes SR. Effectiveness of small group social skills lessons with elementary students. Georgia School Counselors Association Journal. 2012;19(1):92–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clonan SM, McDougal JL, Clark K, Davison S. Use of office discipline referrals in school-wide decision making: A practical example. Psychology in the Schools. 2007;44:19–27. doi: 10.1002/pits.20202. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarivate Analytics. (n.d.). Journal Citation Reports. https://mjl.clarivate.com/search-results

- Crutchfield J, Phillippo KL, Frey A. Structural racism in schools: A view through the lens of the national school social work practice model. Children & Schools. 2020;42(3):187–193. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdaa015. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ding, X. (2023). "Characteristics and Outcomes of school social work services: a scoping review of published evidence 2000–2022", 10.18738/T8/7WQNJX, Texas Data Repository, V1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Early TJ, Vonk ME. Effectiveness of school social work from a risk and resilience perspective. Children & Schools. 2001;23(1):9–31. doi: 10.1093/cs/23.1.9. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eber L, Sugai G, Smith CR, Scott TM. Wraparound and positive behavioral interventions and supports in the schools. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10(3):171–180. doi: 10.1177/10634266020100030501. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elsherbiny MM. Using a preventive social work program for reducing school refusal. Children & Schools. 2017;39(2):81–88. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdx005. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elswick SE, Cuellar MJ, Mason SE. Leadership and school social work in the USA: A qualitative assessment. School Mental Health. 2019;11(3):535–548. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-9298-8. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ervin T, Wilson AN, Maynard BR, Bramblett T. Determining the effectiveness of behavior skills training and observational learning on classroom behaviors: A case study. Social Work Research. 2018;42(2):106–117. doi: 10.1093/swr/svy005. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans, N., Lasen, M., & Tsey, K. (2015). Appendix A: effective public health practice project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. A systematic review of rural development research: characteristics, design quality and engagement with sustainability. USA: Springer , 45–63.

- Fein EH, Kataoka S, Aralis H, Lester P, Marlotte L, Morgan R, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R. Implementing a school-based, trauma-informed resilience curriculum for parents. Social Work in Public Health. 2021;36(7–8):795–805. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2021.1958116. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franklin C, Kim JS, Tripodi SJ. A meta-analysis of published school social work practice studies: 1980–2007. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19(6):667–677. doi: 10.1177/1049731508330224. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frey AJ, Alvarez ME, Sabatino CA, Lindsey BC, Dupper DR, Raines JC, Norris MP. The development of a national school social work practice model. Children and Schools. 2012;34(3):131–134. doi: 10.1093/cs/cds025. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garfield E. The history and meaning of the journal impact factor. JAMA. 2006;295(1):90–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.90. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gherardi SA. Policy windows in school social work: History, practice implications, and new directions. School Social Work Journal. 2017;42(1):37–54. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huxtable, M. (2022). A global picture of school social work in 2021. Online Submission 7 (1).

- Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Marlotte L, Garcia E, Aralis H, Lester P, Escudero P, Kataoka S. Adapting and implementing a school-based resilience-building curriculum among low-income racial and ethnic minority students. Contemporary School Psychology. 2017;21(3):223–239. doi: 10.1007/s40688-017-0134-1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Wong M, Escudero P, Tu W, Fink A. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keller J, Grumbach G. School social work: A skills-based competency approach. London: Springer Publishing Company; 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly MS, Benbenishty R, Capp G, Watson K, Astor R. Practice in a pandemic: School social workers’ adaptations and experiences during the 2020 COVID-19 school disruptions. Families in Society. 2021;102(3):400–413. doi: 10.1177/10443894211009863. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly MS, Berzin SC, Frey A, Alvarez M, Shaffer G, O’brien K. The state of school social work: Findings from the national school social work survey. School Mental Health. 2010;2(3):132–141. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9034-5. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly MS, Bluestone-Miller R. Working on what works (WOWW): Coaching teachers to do more of what’s working. Children & Schools. 2009;31(1):35–38. doi: 10.1093/cs/31.1.35. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly MS, Frey AJ, Alvarez M, Berzin SC, Shaffer G, O'Brien K. School social work practice and response to intervention. Children and Schools. 2010;32(4):201–209. doi: 10.1093/cs/32.4.201. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly MS, Frey A, Thompson A, Klemp H, Alvarez M, Berzin SC. Assessing the national school social work practice model: Findings from the second national school social work survey. Social Work. 2015;61(1):17–28. doi: 10.1093/sw/swv044. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lustick H, Norton C, Lopez SR, Greene-Rooks JH. Restorative practices for empowerment: A social work lens. Children & Schools. 2020;42(2):89–98. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdaa006. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Magnano J. A social work intervention for children with emotional and behavioral disabilities. Albany: State University of New York; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2012). NASW standards for school social work services. https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=1Ze4-9-Os7E%3D&portalid=0

- Newsome WS. The impact of solution-focused brief therapy with at-risk junior high school students. Children and Schools. 2005;27(2):83–90. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.2.83. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newsome WS, Anderson-Butcher D, Fink J, Hall L, Huffer J. The impact of school social work services on student absenteeism and risk factors related to school truancy. School Social Work Journal. 2008;32(2):21–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxford University Press. (2022). Children & Schools. https://academic.oup.com/cs

- Phillippo KL, Blosser A. Specialty practice or interstitial practice? A reconsideration of school social work's past and present. Children & Schools. 2013;35(1):19–31. doi: 10.1093/cs/cds039. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips JH. An evaluation of school-based cognitive-behavioral social skills training groups with adolescents at risk for depression. Arlington: The University of Texas; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadzaglishvili S, Akobia N, Shatberashvili N, Gigineishvili K. A social work intervention’s effects on the improvement of school culture1. ERIS Journal-Winter. 2020;2020:45. [ Google Scholar ]

- School Social Work Association of America [SSWAA]. (n.d.). School social work practice model overview: Improving academic and behavioral outcomes. https://www.sswaa.org/_files/ugd/486e55_47e9e7e084a84e5cbd7287e681f91961.pdf

- Thompson AM, Frey AJ, Kelly MS. Factors influencing school social work practice: A latent profile analysis. School Mental Health. 2019;11(1):129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-9279-y. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson AM, Webber KC. Realigning student and teacher perceptions of school rules: A behavior management strategy for students with challenging behaviors. Children and Schools. 2010;32(2):71–79. doi: 10.1093/cs/32.2.71. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Straus SE. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson KR, Capp G, Astor RA, Kelly MS, Benbenishty R. We need to address the trauma: School social workers′ views about student and staff mental health during COVID-19. School Mental Health. 2022;14:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09512-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilde, J. (2004). Definitions for the no child left behind act of 2001: Scientifically-based research. National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition and Language Instruction NCELA .

- Wong DF, Kwok SY, Low YT, Man KW, Ip PS. Evaluating effectiveness of cognitive–behavior therapy for Hong Kong adolescents with anxiety problems. Research on Social Work Practice. 2018;28(5):585–594. doi: 10.1177/1049731516658351. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong DF, Ng TK, Ip PS, Chung ML, Choi J. Evaluating the effectiveness of a group CBT for parents of ADHD children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018;27(1):227–239. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0868-4. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young S, Connolly Sollose L, Carey JP. Addressing chronic absenteeism in middle school: A cost-effective approach. Children and Schools. 2020;42(2):131–138. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdaa009. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (792.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

COMMENTS

Submit Paper. The Journal of Social Work is a forum for the publication, dissemination and debate of key ideas and research in social work. The journal aims to advance theoretical understanding, shape policy, and inform practice, and welcomes submissions from all areas of social work.

Social Work Research publishes exemplary research to advance the development of knowledge and inform social work practice. Find out more. Advertisement. Latest articles ... Call for papers. The NASW journals are accepting manuscripts for upcoming special issues. Learn more. Altmetrics.

what is the readiness of social work students to work with autistic individuals?, ignacio aguilar pelaez. pdf. examining experiences among social workers working with parents who suffer from substance use disorder, alicia alvarado and eleno zepeda. pdf. covid-19, social isolation, and msw students' mental health, cassandra barajas. pdf

Committed to publishing social work and social justice scholarship that aims to improve the lives of communities and individuals who have been historically marginalized, JSSWR prioritizes research grounded in anti-oppressive, antiracist, and intersectional frameworks that challenge existing paradigms and structures that produce and sustain ...

Second, studies of practice research in social work remain scant in Asia and Singapore Webber 2020 Ho et al. 2023;Teo, Koh, and Kwan 2023), with limited insights into organisational contexts ...

Social Work Research publishes exemplary research to advance the development of knowledge and inform social work practice. Widely regarded as the outstanding journal in the field, it includes analytic reviews of research, theoretical articles pertaining to social work research, evaluation studies, and diverse research studies that contribute to knowledge about social work issues and problems.

Social work is acknowledged to be a high-stress profession that involves working with people in distressing circumstances and complex life situations such as those experiencing abuse, domestic violence, substance misuse, and crime (Stanley & Mettilda, 2016).It has been observed that important sources of occupational stress for social workers include excessive workload, working overtime ...

Research on Social Work Practice (RSWP), peer-reviewed and published eight times per year, is a disciplinary journal devoted to the publication of empirical research concerning the assessment methods and outcomes of social work practice. Intervention programs covered include behavior analysis and therapy; psychotherapy or counseling with individuals; case management; and education.

Social Work. Social Work is the premiere journal of the social work profession. Widely read by practitioners, faculty, and students, it is the official journal of NASW and is provided to all members as a membership benefit. Social Work is dedicated to improving practice and advancing knowledge in social work and social welfare.

School Social Work Credential. Recent research on school social workers' practice choices showed that school social workers who endorsed primary prevention in MTSS and ecologically informed practice are more likely to have a graduate degree, be regulated by certification standards, and have less than ten years of work experience (Thompson et ...