Social Network Analysis (SNA) using qualitative methods

In this session we introduce Social Network Analysis (SNA) and consider how social networks can be studied and analysed from a qualitative perspective.

We outline what a qualitative approach to SNA would look like, and how qualitative methods have been mixed with formal SNA at different stages of network projects. We also provide some examples of using qualitative methods alongside formal SNA from our recent research.

Download PDF slides of the presentation ' Mixing methods in Social Network Analysis '

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Mixed Methods Approach to Network Data Collection

Ian w holloway, anamika barman-adhikari, dahlia fuentes, c hendricks brown, lawrence a palinkas.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence can be directed to Eric Rice, University of Southern California School of Social Work, 1149 S. Hill St., Suite 360, Los Angeles, CA, 90015; voice: 213-743-4766; [email protected]

Issue date 2014 Aug.

There is a growing interest in examining network processes with a mix of qualitative and quantitative network data. Research has consistently shown that free recall name generators entail recall bias and result in missing data that affects the quality of social network data. This study describes a mixed methods approach for collecting social network data, combining a free recall name generator in the context of an online survey with network relations data coded from transcripts of semi-structured qualitative interviews. The combined network provides substantially more information about the network space, both quantitatively and qualitatively. While network density was relatively stable across networks generated from different data collection methodologies, there were noticeable differences in centrality and component structure across networks. The approach presented here involved limited participant burden and generated more complete data than either technique alone could provide. We make suggestions for further development of this method.

Introduction

The quality of social network research depends upon the quality of the social network data collected. Social network researchers have identified three primary sources of error that can lead to missing network data: boundary specification ( Laumann, Marsden, & Prensky, 1983 ; Marsden, 2005 ), non-response ( Kossinets, 2006 ; Rumsey, 1993 ; Stork & Richards, 1992 ), and recall bias (e.g., Marin, 2004 ; see Brewer, 2000 for review). It is this latter source of error which is the topic of the present study. We present a description of how researchers can combine data from a more traditional free recall name generator with coded relations from semi-structured interviews. We provide a comparative structural analysis of the three resulting data sets: 1) free recall name generator only, 2) data coded from semi-structured interviews only, and 3) combined data. The approach presented here involved limited participant burden and generated more complete data than either technique alone could provide.

There are a large number of methods for collecting social network data. One of the most common field techniques is to utilize name generators : A question or series of questions that are designed to elicit the naming of relevant alters along some specified criterion ( Campbell-Barrett & Karen, 1991 ; Marsden, 2005 ). Typically, name generators are free recall name generators. Respondents are given a prompt that defines some criterion, for instance, a category of persons such as “family” or “friends” or types of social exchange relationships (e.g., “who do you turn to for advice or support?”). Then respondents are asked to list as many people as they can. In some cases, an upper limit is given to the number of names that can be elicited.

Name generators implicitly make the assumption that respondents list every alter with whom they share a particular relation. For decades, researchers have observed that this is a problematic assumption (e.g., see Brewer, 2000 ; Marsden, 2005 ), and research on recall has clearly established that persons remember at best a “sample” of relevant alters ( Brewer, 2000 ; Marin, 2004 ). The resulting “sample” is a biased one in that it is subject to respondent fatigue and recall bias (e.g., Bahrick, Bahrick, & Wittlinger, 1975 ; Brewer, Garrett & Rinaldi, 2002 ; Hammer, 1984 ; Marin, 2004 ; Sudman, 1988 ). Moreover, this approach may result in large numbers of missing data.

The effects of missing data on the resulting social network structures can be quite dramatic ( Kossinets, 2006 ; Robins, Pattison, & Woodcock, 2004 ). Even when nodes (i.e., actors) or relations (i.e., vertices) are absent at random, overall network properties such as mean vertex degree, clustering, density, number of component sub-graphs, and average path length can all be impacted ( Kossinets, 2006 ). Most sources of error in network data collection, however, are not random and may create additional problems of bias. While problems of censored and truncated data abound ( Dempster et al., 1977 ), truncation problems are generally more problematic since we know less about missing actors and can therefore more easily apply inaccurate corrections ( Laumann et al., 1983 ; Marsden, 2005 ).

Errors from recall bias, a type of truncation ( Brewer, 2000 ; Marin, 2004 ), have been documented; people regularly forget a substantial portion of their network contacts when they are asked to recall them with standard name generators ( Brewer, 2000 ). Marin (2004) found that affective strong ties were most likely to be recalled, as were relations of longer duration. Moreover, she found structural bias insofar as relations with more shared ties in the network were more likely to be recalled. While in most cases recall error tends to be biased toward strong ties, the evidence is somewhat mixed on this point (e.g., Brewer, 2000 ; Brewer & Webster, 2000 ; Sudman, 1988 ; Hammer, 1984 ). Forgetting or failing to enumerate particular ties has serious implications for the structural properties of the resulting networks ( Kossinets, 2006 ). Most solutions to network recall begin with the understanding that a single item--”free recall” name generator will be most subject to recall bias. Brewer (e.g., 2000 ; Brewer, Garrett & Rinaldi, 2002 ), has extensively reviewed the topic and suggested and tested several viable solutions to the problem, including: non-specific prompting, reading back lists, semantic cues, multiple elicitation questions, and re-interviewing.

A mixed method approach: A proposal

As there has been a growing interest in utilizing mixed methods approaches to examining social network process (Bernardi, 2010; Bidart & Charbonneau, 2005; Coviello, 2005 ; Edwards, 2010 ), we seek to address how such methods can be refined. The method described here is not appropriate for the collection of ego-centric network data in the context of survey research, as such endeavors rarely include qualitative semi-structured interviews. Rather, we wish to refine how one may use information from multiple sources in a mixed methods study to create the most comprehensive picture of the social context under investigation. The current study assesses the quality of data that can be collected by combining multiple data collection methods. As suggested by others, qualitative interviews may be useful in collecting network data (Bernardi, 2010; Bidart & Charbonneau, 2005; Coviello, 2005 ; Edwards, 2010 ). We collected data from an online single name generator and coded network data from qualitative interviews, and then combined these data sets. We present the structures of these resulting networks and discuss how data collection such as this could be improved upon in the future.

The study from which these data were derived was part of a randomized control trial (RCT) known as the Cal-40 Study, which was designed to test the scaling-up of evidence based practice (EBP) implementation in California county child welfare, mental health, and juvenile probation departments ( Chamberlain et al., 2008 ). A supplemental mixed-methods study using both semi-structured interviews (qualitative) and a network survey with a free recall name generator (quantitative) determined the processes by which county agency leaders’ obtain EBP information ( Palinkas et al., 2011 ).

Qualitative semi-structured review: results

Agency directors from child welfare, mental health, and probation departments from 13 California counties from the first wave of the Cal-40 Study were asked to participate in a 60–90 minute interview in person or by phone to determine how EBPs were implemented and to whom they go to for information about EBP implementation.

Of the 45 agency directors invited to participate, 38 agreed to be interviewed or designated another professional from their county (e.g., assistant director, deputy director, or manager) to participate (response rate = 84%). In most cases a researcher interviewed these participants in-person at a location convenient to the agency director (n=28, 74%). When this was not possible, agency directors were interviewed by phone (n=10, 26%).

Semi-structured interview topics included how individuals heard about EBPs, what factors facilitated or impeded EBP participation, with whom individuals communicated about EBPs, and the nature of those communications (e.g., advice-seeking, decisions to collaborate, etc). For additional information on the parent study content, see Palinkas et al., 2011 . Participants in the qualitative study were offered a $20 online gift certificate for their participation. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California approved the study.

In addition to network data collected through the web-based survey, semi-structured interview transcripts from the qualitative phase of the study were examined for instances where individuals who were interviewed described communications with other professionals regarding EBPs. These descriptions could involve communication specifically about advice-seeking regarding EBPs or more general discussion regarding EBPs. For example, in one interview of a chief probation officer (CPO) he/she refers to a specific person with whom he communicated and sought advice about an EBP (see quote 1 in Table 1 ). This type of direct reference to advice-seeking can be contrasted with another qualitative interview segment where the respondent, another CPO, spoke more generally about his communications regarding EBPs with professionals from the mental health department in his county (see quote 2 in Table 1 ). Although the CPO was not specifically referring to EBP advice-seeking, he spoke about close collaboration with professionals from other county agencies, therefore we considered those individuals mentioned in this interview as members of the CPO’s social network.

Examples from the Qualitative, Semi-structured Interviews

Two project staff members, who were involved in recruitment and data collection, reviewed all transcripts for instances where names of individuals were mentioned. Of the 38 qualitative interview transcripts examined, all but one contained names of individuals with whom the participant communicated about EBPs. An a priori decision for how to classify individuals named within qualitative interviews was established. Specifically, three different types of name mention patterns were determined: (1) Full name, (2) Partial name with additional confirmable information, and (3) Partial name with no additional confirmable information. For individuals mentioned by participants to be included in the full name category, both first and last name in the same text segment were required. When the interviewee only mentioned the first name of an individual and was prompted by the interviewer to elicit the full name, that particular individual was considered completely identified. These criteria allowed for 100% matching between individuals nominated in the web-based survey and individuals mentioned in qualitative interviews. For example, an exchange in an interview with a mental health director helped to identify an alter (see quote 3 in Table 1 ). In total 30 participants named 122 individuals by their full name in qualitative interviews. Of these participants, on average, 4 nominations were identified in each qualitative interviews (mean = 4.20, sd = 2.69, range = 1–10).

If the respondent mentioned only a partial name and was not prompted by the interviewer to gain the last name of the individual mentioned, the project staff examined the context of the discussion in which the partial name appeared. If there was additional information provided (e.g., title of the individual mentioned), project staff used the partial name and the additional information to determine whether or not this individual was a previously identified member of the network. When this could not be done through information already available from the web-based survey and interviews, project staff conducted internet searches that included the name, county, agency and whatever additional details were provided in the context of the interview. In one instance, the project staff had the county and titles of each of the individuals about whom the respondent referred to (see quote 4 in Table 1 ). Through examination of the project database and subsequent internet searches, the project staff was able to confirm the identity of these individuals mentioned by the participant during that interview. In total, 25 participants named 39 individuals by partial name in qualitative interviews. Twenty five of these 39 individuals’ identities were confirmed (64%). Of these participants, on average, 1.5 nominations were identified in qualitative interviews (mean = 1.56, SD = 0.77, range = 1–3).

The final category included individuals for whom partial names were given without any additional confirmable information. In one example, there were two full names and one partial name with a broad location (i.e., San Francisco; see quote 5 in Table 1 ). To find the full name of the individual whose partial name was mentioned above, a number of internet searches took place including the name of the interviewee and the partial name, the names of the other individuals mentioned by full name and the partial name, and a combination of full names and partial names with the location mentioned. If no matches could be found, it led to the classification of this individual in the third group. When no first name was mentioned and the title “Judge” or “Doctor” was mentioned before a last name without confirmable additional information, these individuals were also placed in the third group. In total, 10 participants named 10 individuals in qualitative interviews by partial name without confirmable information. Of these participants, each only had 1 nomination of this type.

Network survey with free recall name generator: results

Of the 38 county officials who were interviewed, 30 (79%) agreed to participate in the subsequent web-based social network survey. These individuals were asked to list up to 10 individuals with whom they communicated about EBP implementation. Specifically, the question for the name generator asked participants to: “Name [up to 10] individuals for whom you have relied for advice on whether and how to use evidence-based practices for meeting the mental health needs of youth served by your agency.” Data was also gathered on participant gender, county agency, position in the agency, and number of years in the current position. On average, participants nominated approximately 3 social network members (mean = 2.70, SD = 3.02, range = 0–10). Respondent time spent on the survey ranged from 3:10 minutes to 27:31 minutes.

Analyses for the present study were conducted using UCINet 6 (Borgatti, Everett, & Freeman, 2004). Nodelists for all three datasets (i.e., survey data, qualitative interview data, and combined data) were entered into UCINet to create data matrices, which were then transformed into social network diagrams using NetDraw 2.090 ( Borgatti & Everett, 2002 ). To compare properties of the three networks, a number of standard network measures were calculated, including number of nodes, number of directed ties, density, number of unique components, size of the largest component, directed degree centrality, and betweenness centrality (see Wasserman & Faust, 1994 for descriptions of these measures).

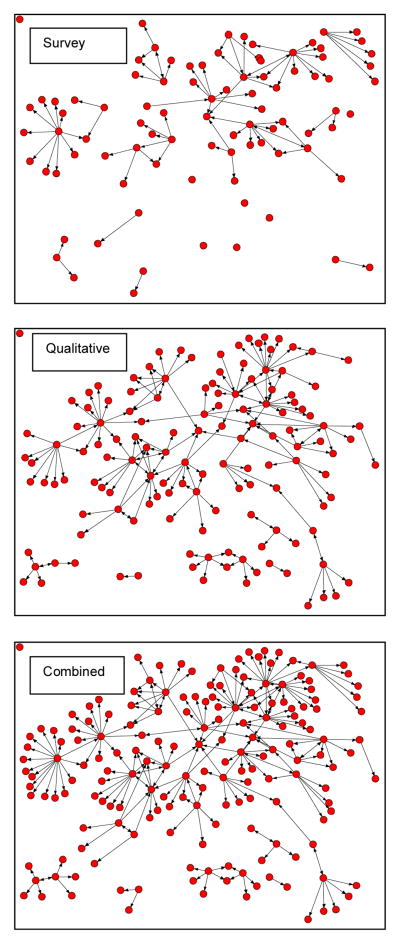

Figure 1 presents the network visualization of the three different networks that were generated from the two data sources: (1) the network constructed only from the social network survey, (2) the network constructed from the qualitative interview data (including the 10 names which were unconfirmed), and (3) the combined network created by merging both data sources into one adjacency matrix. We used the spring embedding algorithm in NetDraw ( Borgatti & Everett, 2002 ) to place the nodes based on connections in the combined data.

Network diagrams based on the web-based survey, qualitative interviews and combined data

One can easily identify several differences across these three network visualizations (see Figure 1 ). There was a steady increase in the number of nodes and ties as one moved from the survey data to the qualitative data, and to the combined data. The survey-generated network contained only 89 nodes with 81 directed ties, whereas the qualitative interview-generated network contained 136 nodes with 171 directed ties, and the combined network contained 176 nodes with 227 directed ties.

The number of discrete network components and the size of those components were impacted by the inclusion of different data sources. While the survey had 18 components, the largest component had only 36 nodes and constituted 40% of that network. The qualitative interview data yielded 7 components, the largest of which contained 112 nodes (82% of that network). Finally, the combined network also had 7 components, the largest of which contained 149 nodes (85% of the resulting network).

Centrality measures were also impacted by the different data sources used, particularly the variance in those metrics. As illustrated in Table 2 , the in-degree, out-degree, and betweenness centrality scores increase when the two data sources are combined and the standard deviations of the metrics likewise increase. In contrast, network density was relatively stable across data sources. One percent of possible relations were present in the survey data, 0.9% in the qualitative interview data, and 0.7% in the combined data. It is important to remember that density and network size are linked, such that as network size increases, network density tends to decrease ( Friedkin, 1992 ), which may explain the slight decline in density in the larger network specifications.

Network Level Measures Across Three Data Sources

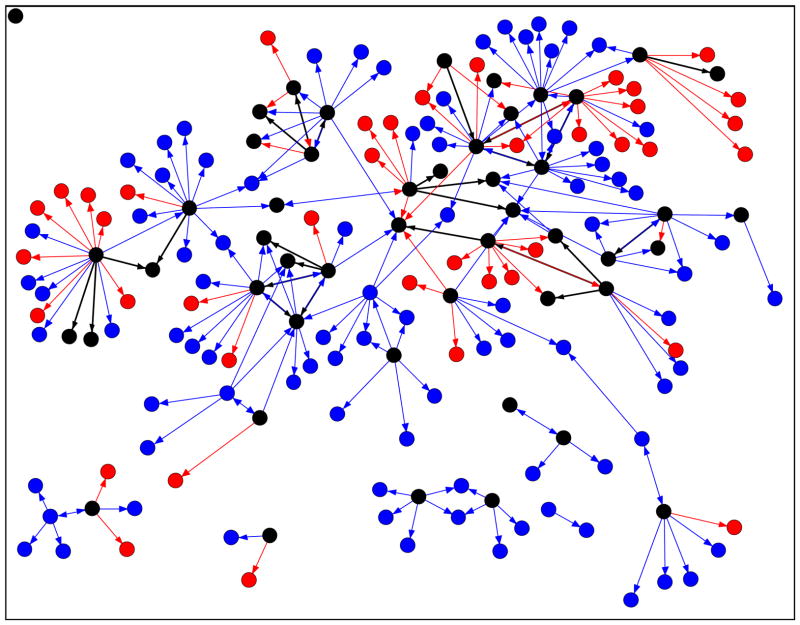

Importantly, there is relatively little overlap between the two different data sources. Figure 2 provides a visualization of the network, which is color-coded to show data source. Black nodes and ties are present across both data sources, red nodes and ties are present only in the survey data, while blue nodes and ties are present only in the qualitative interview data. The number of black nodes and ties is relatively small. Indeed, only 49 of the nodes appeared in both data sets (27.8% of the total nodes), and only 25 ties appeared in both data sets (11.0% of the total ties). The survey data provided 40 unique nodes (22.7% of nodes) and 56 unique ties (24.7% of ties). The qualitative data provided 87 unique nodes (49.4% of nodes) and 146 unique ties (64% of ties).

Total network, comprised of maximal set of nodes and ties, with data source depicted (n=176)

Notes: Circles = Nodes, Arrows = Ties, Red = Survey Only, Blue = Qualitative Interview Only, Black = Both Data Sources.

Further examination of the network visualization, illustrates that some components are dependent upon the intersection of the two data sources. In particular, the component at the bottom left of the diagram in Figure 2 is incomplete in the absence of the multiple data sources. The small triad toward the bottom left of the diagram depicts a respondent who nominated two different alters in the two different data sources.

The data collected by the qualitative interviews provides critical connections, which increase the size of the largest component. Without the qualitative data, the black node on the bottom right in Figure 2 would appear to be a dyad connected, only to the one node nominated in the survey. In the qualitative interview, this person discussed several other network connections, including a node mutually nominated by another participant, who in turn nominated yet another participant, creating a two-step bridge to the largest component.

The present study adds to a growing body of literature advocating the use of mixed-methods approaches to social network data collection (Bernardi, 2010; Bidart & Charbonneau, 2005; Coviello, 2005 ; Edwards, 2010 ). Our technique combined data collected from a web-based survey free recall name generator with data collected from qualitative, semi-structured interviews. It is evident from both the network visualizations and the structural metrics that neither data source unto itself provided a complete picture of the network space. These results are consistent with the body of evidence that has suggested that free recall name generators will result in recall error (e.g., Brewer, 2000 ; Marin, 2004 ). Some indices of the overall social network, such as density, may be moderately affected by the method of collecting social network data, but it is likely that the local topology of links involving individual nodes can differ dramatically differ, as we saw from the triple in the lower left hand corner of Figure 2 . Such differences may be crucial in the adoption of EBPs or the formation of partnerships that support full implementation of these methods ( Brown, et al., 2012 ).

Combining data from a survey, which uses single name generator and qualitative interviews, takes advantage of three proposed solutions to recall bias: Semantic cues, multiple elicitation, and re-interviewing ( Brewer, 2000 ). Like other techniques employing semantic cues, the qualitative interview allows the researcher to ask the respondent about other relations, which are similar to ones already mentioned in the context of systematic follow-up questions to answers about social network processes. The semi-structured nature of qualitative interviewing makes extensive use of a variety of domains and prompts to elicit information about social network processes, a basic multiple elicitation technique. Finally, this approach benefits from re-interviewing by having a distinct survey and qualitative interview. The two interviewing techniques are quite different, which we believe may relieve some participant burden. The time involved in qualitative interviews is not trivial, but the conversational flow of such techniques tends to lessen participant fatigue generated by tedium.

Like many innovations in social network research, this new technique arose from empirical observations ( Freeman, 2004 ). Initially, the research team believed that the web-based social network survey would provide the structural information for all subsequent analyses and the qualitative interview data would be used to elucidate the social context of these structures. Because the qualitative interviews were conducted first, the research team had an intuitive sense of the breadth of ties and the interconnectivity of the network space. As the network data from the free recall name generator was analyzed, it appeared to be an inadequate depiction of the network structures that had been described in the qualitative interviews, especially since these same respondents completed the survey after the interview. This observation prompted the team to return to the qualitative interviews and “mine” them by coding the network data that was contained within the text of the transcripts. As one can clearly see by the preponderance of blue nodes in Figure 2 , significant additional data were collected.

Moving forward, we recommend first collecting survey data on social network structures using name generators. Next, qualitative interviews regarding social network processes should be conducted. This ordering would allow interviewers to prepare for the qualitative interviews by initially reviewing the list of nominated alters from the network survey and preparing to ask follow-up questions based on this information. When new alters are discussed (i.e., persons not on the list) the interviewer may probe with additional questions about the attributes of these newly-named alters. Subsequently, if during the course of the qualitative interview, a participant does not discuss people on the nominations list, the interviewer can use the unrecalled names as additional probes for the qualitative interviews. By this method, one collects more “complete” network and interview data wherein the resulting structural data would be identical, and where one would have a depth of information about both structure and social process.

An additional benefit of the process oriented name generator approach we describe in this paper is the ability to triangulate social network data through qualitative data. Triangulation refers to using multiple data collection techniques to study the same phenomenon ( Denzin, 1978 ). This process of triangulating data helps to establish measurement validity and can be very useful to social network researchers. With our proposed variation to this data collection strategy, social network researchers would be able to completely verify nominations from a single-name generator, while giving participants the opportunity to expand upon this name generator, allowing for greater certainty in the results of the single name generator.

Limitations

As with any study of a novel method, there are limitations to our work. Use of online surveys to elicit social network data has been shown to produce lower quality data than offline ( Matzat & Snijders, 2010 ) and telephone data collection strategies ( Kogovšek, 2006 ). It is our hope that the addition of qualitative interview data improved the overall quality of our data; however, we are unable to verify this from the present study. We acknowledge that the average number of alters nominated by participants in the web-based survey was low, indicating that web-based survey may not be the optimal name generator methodology used to complement qualitative interviewing. Future work should seek to elucidate differences in network structure based on the context in which name generators are given when combined with qualitative data collection techniques.

Respondent burden in network data collection is a major concern and has been addressed previously by randomly sampling alters nominated by an individual and eliciting additional information only on those randomly selected alters (McCarty, Killworth, & Rennell, 2007; Golinelli et al., 2010 ) in order to maximize data quality while minimizing respondent burden. Although we suspect that the process oriented name generator approach would require less participant burden than a repeated single-name generator, we did not compare these two approaches or ask participants about the experience of being asked to complete a web-based survey in addition to a qualitative interview.

Conclusions

The method described here may not be of utility not to survey researchers, especially as much as researchers working in the area of intervention and implementation science. There is a growing desire among implementation science and translational science researchers to understand the community-level network processes impacting these often large-scale, expensive programs ( Palinkas et al., 2011 ; Brown et al., 2012 ; Chamberlain et al., 2008 ). We would like to suggest that research teams who have access to extant qualitative data sets that routinely probe for social relations consider coding these data into network data as we did here. In many cases, participant burden and field staff time are more costly than post-hoc data coding. Many qualitative research projects in the social sciences focus on key relations among people (e.g., social support) and these qualitative data sets present unique opportunities for “mining” with the coding techniques we outline here. There may be a wealth of un-coded network data languishing in the offices of our readers.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the W.T. Grant Foundation (No. 9493), National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH076158), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30 DA027828). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the W.T. Grant Foundation or National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Eric Rice, School of Social Work at the University of Southern California.

Ian W. Holloway, Department of Social Welfare at the University of California, Los Angeles

Anamika Barman-Adhikari, School of Social Work at the University of Southern California.

Dahlia Fuentes, School of Social Work at the University of Southern California.

C. Hendricks Brown, Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami.

Lawrence A. Palinkas, School of Social Work at the University of Southern California

- Bahrick HP, Bahrick P, Wittlinger R. Fifty years of memory for names and faces: A cross-sectional approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1975;104(1):54. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernardi L. A mixed-methods social networks study design for research on transnational families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011 Aug;73:788–803. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bidart C, Charbonneau J. How to generate personal networks: Issues and tools for a sociological perspective. Field Methods. 2011;23(3):266–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borgatti SP. NetDraw: Graph visualization software. Harvard: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Ucinet for windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brewer DD. Forgetting in the recall-based elicitation of personal and social networks. Social Networks. 2000;22(1):29–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brewer DD, Garrett SB, Rinaldi G. Free-listed items are effective cues for eliciting additional items in semantic domains. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2002;16(3):343–358. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown CH. Protecting against nonrandomly missing data in longitudinal studies. Biometrics. 1990;46:143–155. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown CH, Kellam SG, Kaupert S, Muthén BO, Wang W, Muthen LK, Chamberlain P, PoVey C, Cady R, Valente TW, Ogihara M, Prado GJ, Pantin HM, Szapocznik J, Czaja SJ, McManus JW. Partnerships for the design, conduct, and analysis of effectiveness and implementation research: experiences of the Prevention Science and Methodology Group. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39:301–316. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0387-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell-Barrett A, Karen E. Name generators in surveys of personal networks* 1. Social Networks. 1991;13(3):203–221. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(91)90006-F. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chamberlain P, Brown CH, Saldana L, Reid J, Wang W, Marsenich L, Cosna T, Padgett C. Engaging and Recruiting Counties in an Experiment on Implementing Evidence–Based Practice in California. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(4):250–260. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0167-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coviello NE. Integrating qualitative and quantitative techniques in network analysis. Qualitative Market Research. 2005;8(1):39–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1977;39:1–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Denzin NK. The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards G. Mixed-method approaches to social network analysis. 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman LC. The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science. Vancouver: Empirical Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedkin NE. An expected value model of social power: Predictions for selected exchange networks. Social Networks. 1992;14(3–4):213–229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Golinelli D, Ryan G, Green HD, Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Wenzel SL. Sampling to reduce respondent burden in personal network studies and its effect on estimates of structural measures. Field Methods. 2010;22(3):217–230. doi: 10.1177/1525822X10370796. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammer M. Explorations into the meaning of social network interview data* 1. Social Networks. 1984;6(4):341–371. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kogovšek T. Reliability and validity of measuring social support networks by web and telephone. Metodoloski Zvezki. 2006;3(2):239–252. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kossinets G. Effects of missing data in social networks. Social Networks. 2006;28(3):247–268. [ Google Scholar ]

- Laumann E, Marsden P, Prensky D. The boundary specification problem in network analysis. Applied Network Analysis: A Methodological Introduction. 1983:18–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazer D, Pentland A, Adamic L, Aral S, Barabasi AL, Brewer D, Christakis N, Contractor N, Fowler J, Guttmann M, Jebara T, King G, Macy M, Roy D, Van Alstyne M. Computational social science. Science. 2009;323:721–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1167742. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marin A. Are respondents more likely to list alters with certain characteristics? Implications for name generator data. Social Networks. 2004;26(4):289–307. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marsden PV. Recent developments in network measurement. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. 2005;8:30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matzat U, Snijders C. Does the online collection of ego-centered network data reduce data quality? An experimental comparison. Social Networks. 2010;32:105–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robins G, Pattison P, Woolcock J. Missing data in networks: Exponential random graph (p*) models for networks with non-respondents. Social Networks. 2004;26(3):257–283. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumsey DJ. Doctoral dissertation. 1993. Nonresponse models for social network stochastic processes (Markov chains) Retrieved from The Ohio State University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stork D, Richards WD. Nonrespondents in communication network studies. Group & Organization Management. 1992;17(2):193–209. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sudman S. Experiments in measuring neighbor and relative social networks. Social Networks. 1988;10(1):93–108. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: Methods and applications. New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (514.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Subject index

A critical examination of the principles and practice of qualitative research is provided in this book which examines the interplay between context and method, making it invaluable for both the experienced and the beginning researcher. A range of methodological and practical issues central to the concerns of qualitative researchers are addressed. These include: the validity and plausibility of qualitative methods; the problems encountered using specific techniques in a range of social settings; and the moral issues raised in qualitative research. These themes are related to practical issues which are illustrated by a breadth of examples and in-depth case studies. The contributors look at the methods and strategies that they have used to study everyday life, and make suggestions to readers on why and how they might conduct their own studies. They raise issues that go beyond `cookbook' discussions of issues such as how to enter social settings, manage the subjects of one's research and ask `good' questions in the process of formulating research strategies. These issues are addressed within the framework of the larger purposes and uses of qualitative research where specific methodological problems are not used as ends in themselves.

Network Analysis and Qualitative Research: a Method of Contextualization

- By: Emmanuel Lazega

- In: Context and Method in Qualitative Research

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781849208758.n9

- Subject: Anthropology , Business and Management , Criminology and Criminal Justice , Communication and Media Studies , Economics , Education , Geography , Health , Marketing , Nursing , Political Science and International Relations , Psychology , Social Policy and Public Policy , Social Work , Sociology

- Keywords: actors ; Boston ; business law ; collective action ; firms ; identity ; lawyers ; litigation ; negotiation ; offices ; organizations ; status ; symbolic interaction

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

A method of contextualization

Part of sociologists' work is to contextualize individual and collective behaviour (Silverman and Gubrium 1994). Contextualization has both a substantive and a methodological dimension. Substantively, it means identifying specific constraints put on some members' behaviour and specific opportunities offered to them and to others. Methodologically, it is a necessary step for comparative analysis and for appropriate generalization of results.

Network analysis is an efficient way of contextualizing actors' behaviour, based on description and inductive modelling of a specific aspect of this context: the relational pattern, or ‘structure’, of the social setting in which action is observed. It requires collecting specific data on the relationships and exchanges between all the members, and analysing these data using specific procedures. 1 In fact, it can be seen as a systematic and formalized version of a kind of analysis that sociologists and ethnographers have always done intuitively: collecting information on relationships among members of a social setting, mapping these relationships using visual graphs, clustering members in different subsets along different criteria (for instance, similar characteristics, similar political alignments or similar ties to others). Its technical development during the 1970s and 1980s, however, has provided sociology with new concepts and has renewed old theoretical debates. Based on this method, a new form of ‘structural’ sociology has developed. It uses its own concepts - such as structural equivalence, cohesion, centrality or autonomy - to participate in developing the theory of individual and collective action. 2

This is especially the case with complete networks; that is, networks in which researchers have information on the presence or absence of a tie [Page 120] between any two members of the setting. As a consequence, organizations have been among the settings most studied by network analysts (besides urban communities, kinship systems and company boards; see Nohria and Eccles 1992, for a review). Although certain general topics are dominant in this production (such as organizational integration; relationships between centrality, autonomy and power; influence of ties on decisions; informal discriminatory mechanisms and invisible competitive advantages), such studies deal with many substantive issues. For instance, they describe the ways in which ‘friendship’, advice or influence relationships cut across internal hierarchical, functional and office boundaries. They show the ways in which systems filter information reaching their members and the effects they have on the distribution and exchange of resources among them.

As a method of contextualization of behaviour, network analysis can dramatically enhance qualitative research. Conversely, it is impossible to design a network study, or to interpret the results provided by this type of analysis, without having previously performed a careful ethnography of the setting using classical approaches and questions. Used exclusively on its own, network analysis is a purely formal exercise. This chapter is meant to convey the spirit in which such studies are conducted. I first summarize, in a non-technical way, the standard procedures of network analytical approaches. Secondly, I provide an illustration, based on a case study, of the result of two of the main procedures. Thirdly, I look at the way network analysis and symbolic interaction can be combined by the practice of ‘multi-level’ contextualization. Finally, I summarize the added value provided by this method to qualitative approaches and some precautions to be taken when using it.

Bridging the micro and macro levels

A complete (analytically closed) social network is generally defined as a set of relations of a specific type (for instance, advice, support or control relationships) between a defined set of actors. Network analysis is the name given to a number of procedures for describing and modelling inductively the pattern of relations or ‘relational structure’ in this set of actors. Therefore, analytically speaking, relationships among actors have priority over their individual attributes. Structural reasoning is usually differentiated from ‘categorical’, which is based on more standard statistical reasoning. Researchers start with relations and structures, before they bring in characteristics of actors or actors' behaviour, in order to make sense of the structures emerging from the analysis, to explain the emergence of this particular structure, or to explain the observed behaviour as a function of actors' position in it. The main point is that researchers start with data on relations, adding information on attributes and additional behaviour only at a second stage. The main contribution of this method to theory-building is its capacity to contextualize behaviour by describing relational structures in a way that bridges the individual, relational and structural levels of analysis.

Describing the relational structure of a social setting first consists in identifying sub-sets of actors within this system. Such sub-sets can be reconstituted based, for instance, on measurement of the ‘cohesion’ or density of ties among members: one may say, for instance, that a sub-set of members constitutes a ‘clique’ when relationships among them are direct or strong. Sub-sets may also be reconstituted based on measurements of members' ‘structural equivalence’: in that case, actors are clustered together in a sub-set called a ‘position’ or ‘block’ because they share a similar relational profile (they have approximately the same type of relationships with the other actors in the setting, and not necessarily because they have strong ties with one another). Thus, structurally equivalent actors are located in the relational structure in an approximately similar way, which means that they may have, for instance, at the time of the fieldwork, the same ‘enemies’ and the same ‘friends’, be paralysed by similar constraints or be offered similar opportunities and resources.

Based on this initial description of the relational structure, structural analysis can be said to consist in three types of procedure:

- Procedures reconstituting the morphology of the setting using partitions and descriptions of relations between sub-sets: network analysis reconstitutes ‘cliques’, ‘blocks’, or ‘positions’, but also relationships between such sub-sets, which is one of its most significant differences from classical sociometry. The latter did not leave the relational levels of analysis to reach the ‘structural’ one.

- Procedures for positioning of actors in this structure. Each member of the social system can be located in this structure, for instance, based on his/her membership in a clique or in a position, or with individual scores such as centrality, prestige or autonomy. Such procedures are of particular interest to theoreticians because of their flexibility: they allow a constant back and forth movement from the individual and local level to the structural and global level, without losing sight of the individual (as would standard statistical aggregations of individual attributes).

- Procedures associating members' position in the structure with their behaviour. The pattern of relations among actors can be considered to be an independent variable (among others) and its influence on members' behaviour disentangled from other effects and measured.

Contextualization works here through an association between members' position in a relational structure and their behaviour. In theory as well as in practice, this association between position and behaviour is never a deterministic one. It only describes trends. For instance, it often happens that some social settings cannot be partitioned in cliques or clearly defined positions, or that a considerable proportion of members have a unique relational profile (that is, which is not very similar to that of any other member of the setting). Therefore, researchers must constantly compare threshold effects, control for results by using different clustering or partitioning methods, mobilize their ethnographic knowledge of the field to choose what they [Page 122] consider to be the most reliable technique, and make sense of the results within such boundaries.

The use of network analysis requires two additional but important preliminary tasks: a justification of the boundaries defined for the social setting under examination, as well as the relationships used to reconstitute the informal structure (Marsden 1990). Concerning boundaries, rigid delimitations of a social setting are always arbitrary, but the flexibility of network analysis offers ways of defining and redefining them in an analytical and exploratory way. Usually, social systems do not have clear boundaries, and this flexibility allows researchers to define temporary boundaries after exploration of the process of boundary definition by the members themselves. Two comments can be made regarding the definition of the relationships involved. First, the pattern of any network of ties - for instance the advice network in the firm - can be considered to be an approximation of the relational structure of this organization. Technically, network analysis can study networks separately; it can also superpose them and reach a transverse overall view of the relational structure. The question of which specific tie produces the pattern which is the closest to the overall informal structure is a substantive one. Secondly, the study of a specific network is not a goal in itself. It is part of the study of behaviour and processes that researchers are trying to contextualize. Without dependent variables, the description of the structure often remains sterile. In that sense, observing a specific network must have a meaning for the behaviour under consideration. The method itself does not establish a priori a hierarchy between the relations selected and examined. To give more importance to one type of relation than to another is a choice for which researchers must account prior to fieldwork.

The pattern of relationships that emerges from this analysis represents an important dimension of the structure of the setting. The specificity of this method is that this dimension of the structure has an internal and an external reality. It is internal in that it is built inductively based on the specificities observed among members, often identified and interpreted by them. It becomes external in that it characterizes a collective level on which separate individual members do not have much influence. Here, the distinction between micro and macro levels becomes much more manageable than with ‘usual’ statistical techniques because this method allows the researcher to travel from one to the other in a very flexible way. When interpreting the pattern at the structural level, it is always possible to go back to the individual level, check who belongs to which position, then reason again at the collective level using that information.

As in classical theory, the conceptual link between structure and behaviour is provided by the notion of role. However, in current network analysis this notion has two distinct meanings. The first definition refers to the function of a position (that is, the sub-set of structurally equivalent members). In a network where a specific resource flows, relations between positions usually display a division of labour in the production and exchange of this resource. It is often hypothesized that members of a position who are integrated in the [Page 123] network in a relatively similar way will tend to have similar behaviour in this system of production and exchange. The second definition refers to a combination of relations compounding two or more different networks. Members' behaviour is not necessarily exclusively determined by their relations observed here and now, in one single network, but by their integration in several different networks. For example, one's spouse's boss can be considered to be a role because it articulates two different ‘relational worlds’ 3 White et al. (1976) are the first to have tried to partition collections of relations and to conceptualize the notion of role for multi-relational data sets. Roles become here complex and abstract constructs marking the simultaneous effect of several networks (past or present) on behaviour.

Network analysis can thus be conceived of as a method of contextualization and quantitative framing for qualitative approaches to members' behaviour. The description of the relational structure by identification of subsets (cliques or positions), in one or several networks, is a way of identifying inductively collective actors present at a specific moment in a social setting, as well as the relationships or exchanges between them. In turn, the description of these relations, or absence of relations, between blocks identifies a system of interdependences between these collective actors. The analysis thus detects underlying regulatory mechanisms and offers useful indications for a qualitative and strategic perspective.

Seeking advice in a corporate law firm

Substantively, I will draw on a case study (Lazega 1992b, 1995) in the sociology of organizations to illustrate one way in which the bridge between micro (individual and relational) and macro (structural) levels is established. The study is based on fieldwork conducted in a New England corporate law firm (71 lawyers in three offices, comprising 36 partners and 35 associates) in 1991. All the lawyers in the firm were interviewed. In Nelson's (1988) terminology, this firm is a ‘traditional’ one, as opposed to a more ‘bureaucratic’ type. It is a relatively decentralized organization, which grew out of a merger, but without formal and acknowledged distinctions between profit centres. It adopted a managing partner structure during the 1980s for more efficient day-to-day management and decision-making, but its managing partners are not ‘rainmakers’ and do not concentrate strong powers in their hands. Given the informality of the organization, a weak administration provides information, but does not have many formal rules to enforce. Although not departmentalized, the firm breaks down into two general areas of practice: the litigation area (half the lawyers of the firm) and the ‘corporate’ area (anything other than litigation).

Interdependence among attorneys working together on a file may be strong for a few weeks, and then weak for months. Sharing work and cross-selling among partners is done mostly on an informal basis. Given the classical stratification of such firms, work is supposed to be channelled to [Page 124] associates through specific partners, but this rule is only partly respected. Partners' compensation is based exclusively on a seniority lock-step system without any direct link between contribution and returns. The firm goes to great lengths - when selecting associates to become partners - to take as few risks as possible that they will not ‘pull their weight’. As a client-oriented, knowledge-intensive organization, it tries to protect its human capital and social resources, such as its network of clients, through the usual policies of commingling partners' assets (clients, experience, innovations) (Gilson and Mnookin 1985) and the maintenance of an ideology of collegiality. Informal networks of collaboration, advice and ‘friendship’ (socializing outside) are therefore particularly important to the integration of the firm (Lazega 1992b).

To illustrate contextualization and bridging of levels of analysis, I focus here on the advice network among lawyers. Advice is an important resource in professional, collegial and knowledge-intensive organizations. In a law firm that structures itself so as to protect and develop its human and social capital (Gilson and Mnookin 1985; Nelson 1988; Smigel 1969), such a resource is particularly vital. Given this importance, one could easily believe that flows of advice in the firm are ‘free’, or at least that they do not encounter structural obstacles which would systematically prevent exchanges of intelligence between any two members. However, even in a context that is saturated with advice, many factors create obstacles for exchanges of ideas. Most importantly, advice-seeking is influenced by the formal and informal structure of the firm. These dimensions of the structure constrain exchanges of ideas among members. In turn, such constraints are managed in different ways by the members of the firm, which creates disadvantages and inequalities among them (Lazega 1995). To follow the flows of advice in the firm, I used the following name-generator which, among many others, was submitted to all the lawyers in the firm:

Here is the list of all the lawyers in the firm. To whom do you go for basic professional advice, not simply technical advice, for instance when you want to make sure that you are doing things right - for instance handling a case? Would you go through this list, and check the names of those persons.

To give an idea of the task performed by the interviewee, here are some of the statements provided along with the sociometric choices:

Usually advice involves something of another area of law, one that I am not practising. Among the people who can answer, I choose those with experience and the smartest, those who have proved that they have good ideas. With associates, it is different: I can ask for their reaction, but I have to decide for myself. One thing I have learned is that nobody knows everything. Don't ignore the young people. The most stupid guy can sometimes have a good idea, (a partner)

It's a mixed bag. If advice includes issues related to firm management, Smith I would ask on ethics type of questions, or on legal conflicts. He's been around longer than most. Jones for anything having to do with the management of the Hartford office, I rely on him for that. Brown for associate staffing type of issues and also general advice too, what he thinks of where the firm is going. Robertson [Page 125] was basically a managing partner in another firm before he came, I can ask him all sorts of questions on what he would do about this or that. (the current managing partner)

On a particular file, I would go to the partner with whom I work on this file. So the list looks a lot like the co-workers list, although not entirely. There have been times where I got other people's perspective, for instance when other partners with whom I have already worked on similar files have helped me, or when I need to know the implications for the client in other fields. I am a corporate lawyer, and the people I ask are usually in the litigation department, (an associate)

In quantitative terms, answers to the question vary extensively. At both extremes, we have a partner who says that he does not need nor ask anyone for advice, and another partner who declares seeking advice from 30 other colleagues. On average, lawyers have in their network 12 colleagues with whom they can exchange basic work-related ideas. However, such indexes may be misleading. They hide structural effects constraining resource flows, as well as advantages from which some members benefit given their position in the informal structure of the firm. Formal as well as informal dimensions of the structure of the firm have an influence on the choice of advisers. Here, I describe briefly the effect of selected formal dimensions. I then use an analysis of structural equivalence to describe more at length the informal relational structure emerging from this advice network.

It is possible to describe the effect of several dimensions of the formal structure on members' choices of advisers. Members' status (partner versus associate), specialty (litigation versus corporate) and office (Boston, Hartford or Providence) all have significant effects on the choices of advisers. For instance, it is much more frequent for associates to seek advice from partners than the other way around. Exchanges of ideas and intelligence in this firm are indeed affected by status games among members. The same is true of members' office and specialty. In this firm, litigators have a significantly higher probability of choosing advisers among other litigators rather than among corporate lawyers. A similar trend is observed among the latter. Thus the formal structure of the firm weighs heavily on advice-seeking behaviour. 4 This reflects the existence of informal and unspoken rules regarding exchanges of advice in this firm.

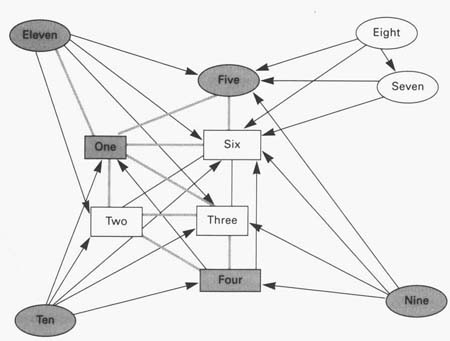

However, such rules are not rigid. The figures show many deviations from them. Thus, other, more informal, constraints also contribute in shaping flows of advice. To describe the ways in which they do so, network analytical techniques provide finer tools for uncovering the invisible pattern of advice-seeking which characterizes this specific firm. This pattern is described below, using an analysis of structural equivalence among members (Burt 1982, 1991), which clusters in the same ‘position’ actors with similar relational profiles in the network examined. Eleven clearly different positions are thus identified. Regardless of the number of individuals in each position, the positions and the relations between them create a complex pattern, or informal structure. Figure 9.1 provides an overview of the relations between these positions.

Figure 9.1 Relations between positions of structurally equivalent actors in the advice network of all lawyers in the firm. Positions represented by a square box are composed mainly of partners; positions represented by a circle are composed mainly of associates. Positions in grey have at least one rival position among the other positions in grey of similar status. Grey lines represent reciprocated advice relationships between positions. A detailed description of these positions and the relationships between them is presented in the Appendix.

A detailed description of these positions and the relationships among them is available in the Appendix. To summarize, Position One, the ‘hard core’ of the firm, is composed of Boston partners of all specialties. Position Two clusters the ‘atypical’ attorneys (either ‘laterals’, i.e. lawyers recruited from other law firms, or of non-lucrative corporate specialties) from both main offices. Position Three is that of Hartford core corporate partners. Position Four is that of Hartford core litigation partners. Position Five is that of the ‘coordinators’, mostly senior women litigation associates in Boston. Position Six clusters the firm's ‘universal advisers’, all litigators in Boston. Position Seven is composed of a group of Boston litigation associates called ‘the boys’. Position Eight is that of the most junior associates in the firm, all Boston litigators and called ‘the beginners’. Position Nine clusters Hartford litigation associates. Position Ten is mainly that of lateral corporate associates in the whole firm. Position Eleven is mainly composed of ‘atypical’ Boston corporate associates. A category of ‘residual’ actors (i.e. actors whose relational profile is different from that of everyone else) does not appear in [Page 127] this figure. As an example of relations between two positions, notice that members of Position Ten tend not to seek advice from members of Position Eleven; or that members of all positions tend to seek advice from members of Position Six.

The analysis of the directions taken by the flows of advice in the firm provides useful insights into the context in which members of this firm exchange this type of resource. Very generally, this context can be described by an obvious stratification between those who are often sought out for advice and those who are almost never (or very little) consulted. Within each of these two categories, interesting absences of relations can be detected and interpreted as specific characteristics of this context.

The first category includes members of Positions One to Six. It is not surprising to find that blocks of partners (as opposed to associates) occupy a central place in this informal pattern. As shown by Figure 9.1, the five positions of partners (One, Two, Three, Four and Five) form a sub-set towards which requests for advice converge from all positions. For instance, exchanges with Position One are very frequent; all tend to seek its members for advice, and they often reciprocate, except with Position Four (Hartford litigation partners sometimes perceived as rivals). Position Six is the most effective at integrating the firm with regard to the distribution of this resource: its members tend to be sought out for advice by the members of all the other positions, but it only reciprocates to Positions One and Five (and especially not to Two, Three and Four).

The second category includes members of Positions Seven to Eleven. For instance, members of Positions Seven and Eight have access to the rest of the firm through Position Five (the coordinators) or Six (the universal advisers) members. Positions Ten and Eleven members are exceptions to this trend. Their members reach directly the most important partners in the firm. Such trends can be explained by the ethnography of the firm: we know, for instance, that most associates in Positions Ten and Eleven are laterals; they did not ‘grow up’ in the firm, and may not have interiorized the norms and informal boundaries which inhibit other associates who came up through the ranks. In addition, given their seniority, they may try to intensify their direct ties with partners to get themselves known and increase their chances of becoming a partner.

Absence of relations between positions show asymmetries in the flows of advice across the firm. They describe the context in which advice-seeking occurs in terms of informal stratification (concentration of choices on an ‘elite’ of advisers and on specific positions in the overall pattern) and polarization (between offices and specialties). In such a context, some members have direct access to advice from important partners, whereas others have to pay a relatively higher price to get access to the same resources. The informal structure thus creates or reflects inequalities among members. Moreover, to seek advice, members also cross the boundaries identified above in the description of the effect of specific dimensions of the formal structure. Such infractions to the rules mav be tolerated for some, and less for others.

For instance, concerning the absence of exchanges among associates, notice that members of Positions Seven, Eight, Nine and Eleven exchange advice within their own group, but very little with the members of other positions. This may be explained by the fact that members of each group have to strike a fragile balance between cooperation and competition. They need each other for advice, but they also tend to be rivals in their relationships with partners. This is particularly true for the members of Positions Five, Nine, Ten and Eleven who were supposed, at the time of the fieldwork, to come up for partnership in the next two years. This competition between associates can result in the design of different relational strategies. Position Five members, for instance, may try to reduce the number of situations in which the members of other positions of associates will get a chance to show their capacity to provide advice, for instance by insulating them in compartmentalized domains defined by traditional and formal internal boundaries. Similarly, lateral or ‘foreign’ (from another office) associates may let themselves be used more often because they are perceived to be easier to exploit or less threatening in terms of loss of status for the advice-seeker.

But the most striking and special aspect of the pattern in Figure 9.1 is the absence of direct reciprocity between certain positions of partners (between Positions One and Four, and between Positions Three/Four and Six). Focusing on the relationships among partners shows again that the One-Six axis is dominant in the control of the flows of advice, but also the absence of reciprocity in these flows, especially among Boston and Hartford litigation partners who compete for the best associates, and for status and prestige within the firm. This asymmetry - which cannot be explained by economic incentives to withhold advice or let other partners down - is even stronger when Figure 9.1 is simplified to retain only reciprocal relations between positions, i.e. true collective exchanges of advice. Polarization between Hartford and Boston is still present, as well as the centrality and power of Position One in terms of advice flows. Members of this position, for instance, obviously prefer to seek advice from associates of Position Five rather than from their own partners in Position Four.

A compartmentalized structure emerges, where some have more or better resources to deal with competition and get access to resources such as advice, whereas others are clearly cornered and dependent. This context of advice-seeking is thus constraining in terms of efficiency, but also in terms of control and internal politics. Although exchange of advice often justifies the existence of such firms, actors' strategies at different levels often orient these flows and structure a ‘market’ for advice in a specific way.

To summarize, this example started with the effect of dimensions of the formal structure (boundaries imposed by stratification, division of work and differences in office membership) on the flows of advice. A network analytical procedure has described the pattern of advice relationship at the collective and structural level. This pattern represents the relational context in which individual members seek advice from one another. In turn, this contextualization of individual behaviour helps in understanding how members [Page 129] strike a balance between competition and cooperation within the firm in terms of access to, and management of, such resources. It shows in particular how flows of advice are clearly shaped by symbolic games of membership, recognition, inclusions and exclusions, identification and social differentiation. The description of this specific advice-based dimension of the relational structure of the firm allows us to look at the relationship between members' position in the structure, their behaviour in terms of advice-seeking, and their advantages or disadvantages in terms of access to resources. The same approach can help link any relational structure to any behaviour, including assertions, attributions of different meanings to different stimuli (Emerson and Messinger 1977; Lazega 1992a) - provided that they are observed in a systematic way - as well as the type of actionis on which interactionist and qualitative studies currently focus.

Network analysis and symbolic interaction

One of the potential uses for this method is to develop the structural dimension of interactionist approaches. It provides rigorous and flexible tools for analysing behaviour at the individual, relational and structural levels simultaneously. Therefore, it is of interest to such approaches when they try to combine both the actor's perspective and the system's perspective in their account of individual and collective action. Compatibility between the two approaches is both methodological and substantive.

Network analysis is an inductive method. This inductive character is precisely what makes it compatible with approaches to social phenomena such as that of symbolic interactionism. From both perspectives, researchers at the beginning of their fieldwork do not have a precise picture of the morphology of their social setting, the number and composition of collective actors in presence, or the configuration of the relationships and exchanges between them. Observers progressively reach this picture of the system and its regulation at the structural level. Although it introduces a quantitative dimension in the analysis, this formalization does not reify the method, nor does it rely on a reified conception of the structure.

As demonstrated by Maines (1977), many symbolic interactionists have taken structures into account, defining the specificity of the contexts in which they were doing research and giving considerable importance to structural constraints when describing actors' behaviour. 5 ‘Structuralist’ symbolic interactionists - from Hughes (1945, 1958) to Freidson (1976, 1986), Bucher (1970), Benson and Day (1976), Day and Day (1977), Strong and Dingwall (1983), Dingwall and Strong (1985) - developed a less ‘subjectivist’ framework than theoreticians more attracted to social psychology. Symbolic interactionist work taking social structure into account relies on a less rigid and less stable conception of the structure than does the functionalist tradition (which is why, from the latter perspective, the interactionist definition of the structure often seemed non-existent). Bur it has not done so in a truly systematic way.

Based on the previous sections, it is possible to argue that network analysis can provide symbolic interaction theory with a systematic contextualization tool. In fact, such a contextualization has multiple levels. This multi-level character is best explained by a link between the concepts of structure, identity and the definition of the situation.

Describing relational structures is only a first step in the contextualization of behaviour. It is based on members' local perception of their ties, which are then aggregated and combined into an informal pattern at the global or collective level. But the construction of ties, or choice of exchange partners, does not happen in a vacuum. A second step consists in looking at the effect of formal structural dimensions on the choices of ties. For instance, members of organizations looking for exchange partners often choose others similar to themselves with respect to various characteristics (for example, specialty, status or office membership). As a consequence, an emergent context of behaviour is itself shaped by background formal contexts. From a symbolic interactionist perspective, the latter can be defined as a set of institutional identities formally attributed to some members, with various degrees of authority attached to them. 6 Consequently, formal dimensions of structure can be said to have a double effect on behaviour, directly and indirectly: directly, because formal structure translates into identities and rules to which members can refer when monitoring their behaviour; indirectly, because they do have an influence on the choices of exchange partners, and therefore on the formation of relational and informal patterns.

Understanding contextualization in this way resonates with the symbolic interactionist conception of the link between structure and individual behaviour or ‘rationality’; that is, the ‘definition of the situation’. This link is based on the concepts of identity and role. Actors use attributes provided by formal and informal structures as sources of identities in their definition of the situation. Contextualization thus has both a theoretical and practical meaning. For theorists of individual and collective action, it means understanding constraints potentially orienting members' behaviour. For actors themselves, it means actually activating specific identities when evaluating the appropriateness of their behaviour (Lazega 1992a).

This multi-level method of contextualization complexifies the study of human behaviour under structural constraints by combining formal and informal dimensions of structure, as well as combining quantitative and formalized approaches with qualitative and ethnographic ones. Network analysis can thus help transform symbolic interaction into a fully fledged theory of collective action capable of expanding its explorations. It solves the main problem that the ‘negotiated order theory’ (Strauss et al. 1963; Strauss 1978) wanted to solve; that is, going beyond the difference between formal and informal structure. Informal sub-sets emerging from the analysis are different from, but closely intertwined with, the formal morphology of a setting. A comparison between prescribed and emergent structures becomes possible because formal (for instance, the chart) and informal dimensions of the structure can be described in the same terms, both being representable as [Page 131] networks of ties and as sets of identities. In addition, attributes of individual and collective actors can be combined with characteristics of their relations. Here again, this points out that, for both approaches, members themselves contribute in constructing the structures which end up constraining their own behaviour. Network analysis as a method of multi-level contextualization can thus help symbolic interaction follow this process and travel from the actor's perspective to the system's perspective and backwards.

Such a rapprochement still raises several conceptual difficulties, to be addressed by theoreticians, or by researchers on a case-by-case basis. First, the existence of ties is inferred from reported or observed interactions, exchanges of resources and common activities. To identify the specific type of interaction or tie of interest in the reconstitution of a network, researchers have to rely on shared meanings specifying such interactions or ties. ‘Shared’ means that the tie and action have to make sense to all the members of a social setting in a broadly similar way. As put by Fine (1991,1992; Fine and Kleinman 1983), structure's reality is separate from its interpretation, but must be mediated through perception of conduct options and external forces. Network analysts know that, in order to reconstitute a network, one needs a clear definition of the ties constituting this network. They rely on the idea that networks are exchange networks. Therefore, the definition of meaningful ties (i.e. ties through which resources flow) is left to the researcher and negotiated with respondents prior to the collection of network data. Network analysts, however, have not given priority to this issue: they do not account much for differences in the way members of a social settings define what resource a specific relationship represents; for instance, for the variety of definitions of friendship among the members of an organization. Furthermore, network analysts have not, up to now, paid much attention to redefinitions of relationships. Members are not assumed to be strategic, capable of changing the meaning of their relationship. The link between renegotiation of the meaning of a relationship and the dynamics of relational structures is not systematically addressed. 7

Secondly, although it is an issue that goes beyond the scope of this chapter, this rapprochement, in order to become truly significant in the study of individual and collective action, has to produce theoretical developments as well. Two issues illustrate the need for such developments: the problem of an inductive and deductive theory of structure, and the problem of an integrated theory of role.