Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

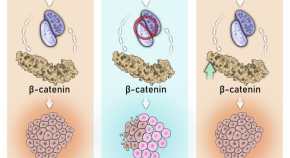

A clump of prostate cancer cells. The blue-green cells are growing, whereas the pink ones are dying by programmed cell death (apoptosis).

Putting the brakes on prostate cancer cells

By alan dove weill cornell medicine.

Prostate cancer hijacks the normal prostate’s growth regulation program to release the brakes and grow freely, according to Weill Cornell Medicine researchers. The discovery, published Dec. 13 in Nature Communications , paves the way for new diagnostic tests to guide treatment and could also help drug developers identify novel ways to stop the disease.

A protein called the androgen receptor normally functions to guide the development of the prostate – signaling the cells to stop growing, act as normal prostate cells and maintain a healthy state. The receptor is activated by androgens or sex hormones like testosterone, which triggers the receptor to bind to DNA, causing the expression of some genes and suppression of others.

But in cancer, the androgen receptor is reprogrammed to tell the cells to continue growing, driving tumor development.

“It’s pretty well known in the field that the androgen receptor gets hijacked in a variety of ways and starts taking on new functions to drive prostate cancer cell growth,” said senior author Dr. Christopher Barbieri , the Peter M. Sacerdote Distinguished Associate Professor in Urologic Oncology, associate professor of urology at Weill Cornell Medicine and urologic surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

This study showed that androgen receptors in prostate cells can work as either an accelerator speeding cell growth or a brake inhibiting it. Tumors redirect the receptors’ normal activity to press the accelerator and release the brake.

Much of the research on prostate cancer has focused on how the androgen receptor activates genes that promote cell growth. However, Barbieri’s team noticed that the protein also loses functions, binding less to some of its normal DNA sites. The researchers hypothesized that those normal binding sites might suppress cell growth, so when the androgen receptor abandons them, the tumor cells can multiply uncontrollably.

To test that, co-first author Michael Augello, who was a postdoctoral fellow at the time, created a panel of artificial proteins, each containing a DNA-binding section of the androgen receptor and either an activating or suppressing module.

“This approach allowed us to examine the normal cell program that remains embedded but hijacked in cancer cells,” said co-first author Xuanrong Chen , a postdoctoral associate in urology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Using these artificial transcription factors, the team then tested all the androgen receptor binding sites in cultured cells, cataloging what each site did in both normal and cancerous cells. That experiment revealed a family of genes that can stop the growth of prostate cancer cells.

“When we turn on the genes controlled by these androgen receptor regulatory elements, the cell’s growth is shut down,” Barbieri said. In contrast, turning on the same genes in healthy prostate cells had no effect.

“It really suggests that these elements are there for normal cells to differentiate and be happy, and the cancer has to rewire them in order to grow,” said Barbieri, a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and also of the Englander Institute for Precision Medicine , both at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Based on their initial results, the investigators screened tissue samples from prostate cancer patients.

“We found that the more the tumors express the normal cells’ androgen receptor program, the better the patient’s prognosis, the better their response to therapies and the better the patient outcome,” Barbieri said. His lab is already developing diagnostic tests based on these results, which could be used to tailor patient treatment regimens.

“The findings also open up the possibility of developing a therapeutic that reactivates the normal regulatory program in prostate cancer cells to restrain their growth,” Chen said.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health; the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation; a MetLife Foundation Family Clinical Investigator Award; and the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Many Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and scientists maintain relationships and collaborate with external organizations to foster scientific innovation and provide expert guidance. The institution makes these disclosures public to ensure transparency. For this information, please see the profile for Dr. Christopher Barbieri .

Alan Dove is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.

Media Contact

Barbara prempeh.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Advances and development of prostate cancer, treatment, and strategies: A systemic review

Sana belkahla, insha nahvi, supratim biswas, nidhal ben amor.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Aamir Ahmad , University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Reviewed by: Azad Alam Siddiqui , Km Mayawati Government Girls PG College Badalpur, India

Wissem Mnif , University of Manouba, Tunisia

*Correspondence: Sana Belkahla, [email protected] ; Insha Nahvi, [email protected]

This article was submitted to Cancer Cell Biology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology

Received 2022 Jul 11; Accepted 2022 Aug 5; Collection date 2022.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

The most common type of cancer in the present-day world affecting modern-day men after lung cancer is prostate cancer. Prostate cancer remains on the list of top three cancer types claiming the highest number of male lives. An estimated 1.4 million new cases were reported worldwide in 2020. The incidence of prostate cancer is found predominantly in the regions having a high human development index. Despite the fact that considerable success has been achieved in the treatment and management of prostate cancer, it remains a challenge for scientists and clinicians to curve the speedy advancement of the said cancer type. The most common risk factor of prostate cancer is age; men tend to become more vulnerable to prostate cancer as they grow older. Commonly men in the age group of 66 years and above are the most vulnerable population to develop prostate cancer. The gulf countries are not far behind when it came to accounting for the number of individuals falling prey to the deadly cancer type in recent times. There has been a consistent increase in the incidence of prostate cancer in the gulf countries in the past decade. The present review aims at discussing the development, diagnostics via machine learning, and implementation of treatment of prostate cancer with a special focus on nanotherapeutics, in the gulf countries.

Keywords: nanotherapeutics, prostate, therapeutic, metastasis, mortality, Saudi Arabia, nanomedications

1 Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is a type of cancer that occurs in a small male gland called the prostate. The main function of the prostate is to produce the seminal fluid that nourishes and transports sperms. PC is one of the most common cancers among men representing a major public health issue as about one man in six is being diagnosed with PC, but it is highly treatable in its early stages. Prostate cancer is usually identified by a blood test to measure prostate-specific antigen levels (PAS), (PSA > 4 ng/ml), a glycoprotein normally expressed by prostate tissue and/or digital rectal examination ( Rebello et al., 2021 ).

Prostate cancer is the second most frequent disease in the world, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) with 1,414,259 new cases around the world, and is the fifth leading cause of male cancer-related deaths. According to Globacan 2020 estimates, it caused 375,304 cases of deaths among men worldwide of all ages (Global Cancer Statistics 2020). In the United States, Africa, and Europe, PC has been found to be the leading cause of death after lung cancer. In Saudi Arabia, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estimated that the number of incident cases was 693, the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) for prostate cancer was 7 per 100,000 men in 2020, and the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) was 2.5 per 100,000 men ( Panigrahi et al., 2019 ). The age-standardized rate (ASR) of PC in Arab countries is relatively low compared to Europe and North America; it may be due to several factors such as the low prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test screening and specific biological differences among Arab men ( Osman et al., 2018 ).

Obesity, unhealthy diet, tobacco and alcohol consumption, family history, racial differences, and age are some of the potential risk factors linked with PC ( Perdana et al., 2016 ). According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), two-thirds of patients diagnosed with PC are either 65 years old or more than that. The average age range during diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years ( Siegel et al., 2018 ).

The purpose of our study is to evaluate and analyze the prostate cancer rate in Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries. We interpreted data from different studies and articles published in the local medical literature worldwide, especially in Saudi Arabia.

2 Epidemiology

2.1 incidence of prostate cancer worldwide.

Based on the International Agency for Research on Cancer 2020 estimates, we have evaluated the incidence and mortality rates of prostate cancer worldwide and in the Arab population taking Saudi Arabia as an example.

Based on Globacan, in 2020, 1,414,259 new cases of prostate cancer were registered worldwide representing around 7.2% of all cancers in men. The estimated number of new cases of prostate cancer is highly variable worldwide ( Table1 ). Europe and Asia have the higher number of new cases 93,173, and 22,421, respectively, with an estimated incidence rate of 33.5% and 26.5%, respectively, compared to non-developed countries such as Africa and Oceania with an incidence rate of 6.6% and 1.6%, respectively ( Table 1 ).

Incidence of prostate cancer worldwide.

Differences in the number of new cases vary extremely between the populations at the highest rate (Germany, 67,959 cases) and the populations with the lowest rate (Bhutan, three cases). The reason for these differences among populations is not entirely clear.

According to a recent statistical analysis, the worldwide variations in prostate cancer incidence might be the result of overscreening in developed countries. It was shown that around 20%–40% of the prostate cancer cases in the United States and Europe were identified by PSA testing.

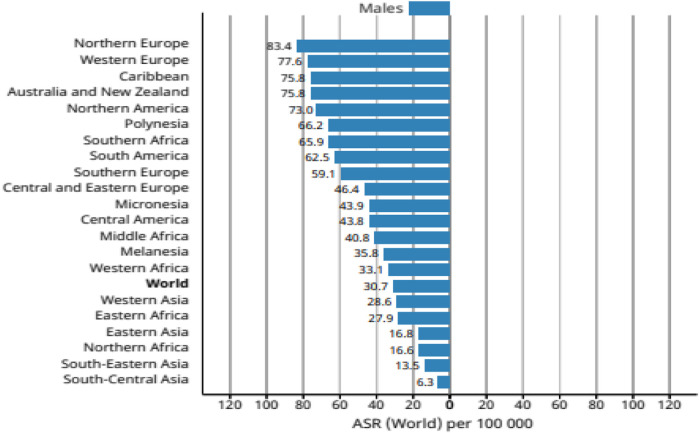

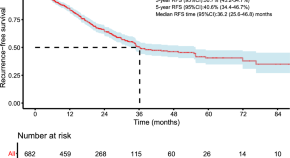

Generally, the rate of incidence of cancer increases with age, the age-standardized rate of patients with prostate cancer (ASR) was highest in Northern and Western Europe (83.4 and 77.6 per 100,000 people, respectively), followed by the Caribbean (75.8 per 100,000 people) and North America (73.0 per 100,000 people) ( Figure 1 ).

Association of obesity with different types of cancers.

Based on new statistics, about 1 man in 41 died of prostate cancer, which led to 375,304 (3.8% of all cancer) deaths globally in 2020 (9,958,133 deaths). Asia has the highest number of deaths (120,593), followed by Europe (108,088). However, the number of death cases in Oceania is lower than that in developed countries with 4,767 deaths ( Table 1 ).

2.2 Distribution of cases and deaths by region among Arab countries

Prostate cancer incidence is lower in Arab countries than in Canada, Germany, and the United States, where extensive epidemiological studies are easier to conduct. In the United States, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer accounting for 12.5% of cases (209,512 new cases) of all new cancers registered in 2020 (1,674,081 cases). In Saudi Arabia, the number of new cases of PC was 693 (2.5% of all cancers) with the crude rate and age-standardized incidence rate being 3.4 and 7.0 per 100,000, respectively, compared to other Arab countries. Qatar has the lowest number of new cases (104) with an ASIR of 21.1 per 100,000, followed by Oman and Kuwait with 186 and 255 new cases, respectively, and ASIRs were 13.8 and 19.6 per 100,000, respectively.

However, the Arab populations in North Africa have a higher number of new cases than the Middle East Arab population. Egypt and Morocco have the highest incidence of new cases with 4,767 and 4,429, respectively, and ASIRs were 13.9 and 23.6 per 100,000, respectively.

The mortality rate in Middle Eastern, North African, and Asian men was found to have a lower prevalence of prostate cancer than Europe, America, and Canada ( Table 2 ).

Mortality rate among Middle East countries and Canada, America, and Europe.

As of 2020, the estimated number of deaths in Saudi Arabia is 204, which is higher than that in Qatar (18 death cases), Kuwait (52 deaths), Oman (73 deaths), and Jordan (142 deaths). However, the ASIR in Saudi Arabia (2.5 per 100.000) is lower than that in Qatar and Jordan with 4.8 and 5.3 per 100.000, respectively. Recent diagnosis of the incidence of prostate cancer worldwide has shown that African–American men have the highest incidence and are more susceptible to developing the disease at an early age compared to other racial and ethnic groups. This result is confirmed not only for African–American men but also for Caribbeans and Black men in Europe. Chu et al. stated that the incidence rate of PC was 40 times higher among African–American men than those in Africa supporting the main hypothesis that the incidence rate of cancer can be related to the genetic background of populations.

In Saudi Arabia, prostate cancer is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in males within the age group of 50–70 years. According to Saudi cancer registry reports, the ASR varies across Saudi regions. The Eastern province and Riyadh have the highest male ASR mean with 9.6 and 7.2 per 100,000, respectively. This is followed by the Makkah region and ASIR region with 5.9 and 4.9 per 100,000 patients. Conversely, in Jazan and Hail regions, the ASR average is 1.8 per 100.000 men, which is the lowest ASR average compared to other regions ( Ali A et al., 2018 ). Based on the grade, localization, and size of the tumor, scientists have identified five types of prostate cancer. More than 95% of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas and up to 5% of prostate cancers may be carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, prostate sarcomas, or transitional cell carcinomas.

Based on the Saudi registry of cancer ( Bandar, 2020 ), the most common PC subtype over 22 years (from 1994 to 2016) was adenocarcinoma (88% of the total cases), followed by carcinoma and sarcomas with 5% and 4% of the total cases.

Prostate cancer, like other types of cancer, does not have an exact cause. In fact, several risk factors may be involved, including genetic mutation, alteration in lipid metabolism, human papillomavirus infection (HPV), and racial differences ( Al-Abdin OZ et al., 2013 ; Ross-Adams H et al., 2015 ; Travis et al., 2016 ; Siegel et al., 2018 ).

2.3 Potential risk factors of prostate cancer

The potential risk factors of prostate cancer can be divided into non-modifiable factors such as age, race, and family history and modifiable risk factors such as diet, physical activity, smoking, and obesity ( Perdana et al., 2016 ).

2.3.1 Non-modifiable risk factors

2.3.1.1 race/ethnicity.

Several recent studies suggest that race and ethnicity are considered as essential risk factors for PC ( Wu et al., 2012 ). According to the latest statistics reports, the incidence and mortality rates of PC remain high among African–American men, West African ancestry from the Caribbean, and South American men than white men (Globacan). However, the lowest incidence of PC is essentially found in Middle Eastern, North African, and Asian men ( Akaza H et al., 2011 ; Powell et al., 2013 ). Data from the National Cancer Institute has shown that African–American men usually have the highest rate (1 in 6 men) compared to other ethnic races such as non-Hispanic White (NHW) men who have a risk of 1 in 8 men being diagnosed with PC in their lifetime. Recent evidence suggests that the difference in the incidence and mortality rate is multifactorial. Comparing the genetic and transcriptome profiles of 596 African–American men and 556 NHW men with PC from different races, researchers ( De Santis et al., 2016 ) suggest that genes controlling the inflammatory pathways (e.g., CCL4, IFNG, CD3, IL33, and ICOSLG) are upregulated in African–American men with downregulation of DNA repair genes (e.g., MSH6 and MSH2) which are highly expressed in non-Hispanic white (NHW) repair pathway (PTEN) deletions (11.5% in African-American vs. 30.2% in NHW) and metabolic pathways involving glycolysis and cell cycle activity ( Nair Sujit S et al., 2022 ).

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are revolutionary studies used over the past decade in genetic research to associate the genetic variation with common diseases or traits in a population ( Jabril et al., 2021 ). Darst et al. (2020) stated that a specific variant (rs72725854) at locus 8q24 was associated with the high frequency of prostate cancer in African–American men, African descent men in Caribbean nations, and West Africans. However, there was no genetic association in populations with European ancestry.

2.3.1.2 Age

Prostate cancer risk may grow with age. Indeed, older men are more prone to get PC than younger men (under 40), who have a lower risk of being diagnosed with the disease ( Howlader et al., 2013 ). The risk of prostate cancer rises rapidly after age 50, and according to analytic studies, about 6 in 10 cases of prostate cancer are found in men older than 65 who have lower overall survival. As a result, it is highly recommended to encourage older men (over 60) to get prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test screening frequently ( Vickers et al., 2010 ; Jayadevappa et al., 2011 ).

2.3.1.3 Family history

In addition to age and race, family history is one of the nonmodifiable risk factors for prostate cancer in men ( Addo et al., 2010 ). Zheng et al. have examined five single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and have found a significant association with PC with a family history of PC ( Jun et al., 2018 ). Gayathri Sridhar et al. (2010) demonstrated that the risk of prostate cancer increased for men with a family history of any cancer or prostate cancer in first-degree relatives (OR = 2.68, 95% CI = 1.53–4.69) and parents alone (OR = 2.68, 95% CI = 1.53–4.69). The Health Professional Follow-Up Study (HPFS) followed up more than 3,695 patients for 18 years (1986–2004) and confirmed a 2.3-fold increased risk of PC with a family history of PC (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.76–3.12). Several other studies confirmed that family history is the most important risk factor compared to age and ethnicity in the development of prostate cancer ( Maria et al., 2021 ). To date mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) and homologous recombination genes (BRCA1/2, ATM, PALB2, and CHEK2) are potentially associated with PC.

2.3.2 Modifiable risk factors

2.3.2.1 obesity.

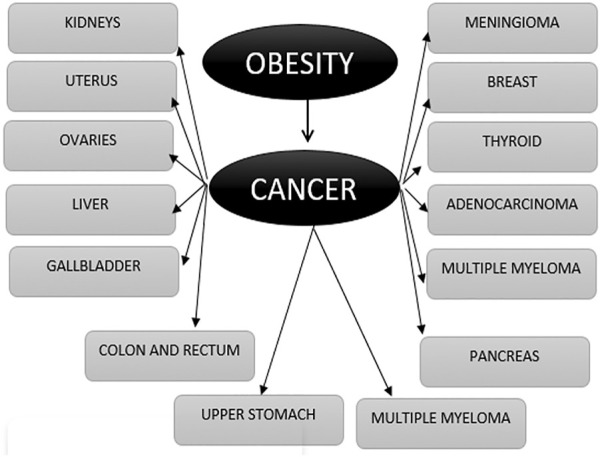

Overweight and obesity are complex diseases involving an excessive amount of body fat. Recent studies confirm that obesity is a serious public health issue and is associated with at least 13 different types of cancers, namely, multiple myeloma (Susanna et al., 2007), meningioma ( Chuan et al., 2014 ), uterus ( Hao et al., 2021 ), breast ( Kyuwan et al., 2019 ), thyroid ( Theodora et al., 2014 ), ovary ( Mauricio et al., 2018 ), liver ( Carlo et al., 2019 ), adenocarcinoma (Katherine et al., 2020), gallbladder ( Larsson SC and Wolk A 2007 ), colon, rectum ( Pavel et al., 2018 ), pancreatic ( Prashanth et al., 2019 ), and upper stomach cancers ( Jacek et al., 2019 ) ( Figure 2 ). Recently, three meta-analyses have confirmed a positive correlation between overweight and prostate cancer incidence ( Boeing et al., 2013 ; Meng-Bo Hu et al., 2014 ).

Steps of the approach using the feature selection technique “CIWO”.

A recent study in Saudi Arabia, including 81 patients in Arar Hospital, demonstrated a significant relationship between prostate cancer and obesity as 62.5% of cases were obese and 37.5% were nonobese ( p < 0.05) ( Abdullah et al., 2017 ). In contrast, Abdulaziz A et al. (2019) stated that there is no association between obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and the incidence of prostate cancer (relative risk = 1.05: 95% CI: 0.51–2.14) in a case-control study that included 2,160 male patients in Saudi Arabia.

2.3.2.2 Smoking and alcohol intake

As Saudi Arabia is an Islamic country, according to Islamic laws, alcohol consumption is completely banned in Saudi Arabia. Thus, the Saudi population is considered to have the lowest alcohol consumption worldwide. In contrast, smoking seems to be a prevalent habit because cigarette smoking was reported by 21.4% among the Saudi population ( Aljoharah M et al., 2018 ). According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), more than 60% of chemicals that are present in a cigarette are carcinogens of class I and class II. Cigarette smoke contains more than 4,000 different chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) ( Huncharek et al., 2010 ) which are hydrocarbons highly linked to skin, lung, bladder, liver, and stomach cancers. PAHs can be genotoxic and bind to DNA-inducing mutations that enhance cancer proliferation, or it can be nongenotoxic and promote cancer evasion and progression ( Baird W.M et al., 2005 ). Therefore, functional polymorphisms in genes involved in PAH metabolism and detoxification may modify the effect of smoking on PC (Noor et al., 2016). An association with smoking could also have a hormonal basis: male smokers were found to have elevated levels of circulating androsterone and testosterone, which may increase PC risk or contribute to cancer progression ( Huncharek et al., 2010 ; Li J et al., 2012 ). A meta-analysis published by Michael Huncharek et al. (2010) evaluated the relationship between smoking and PC and indicated that current smokers had a 24%–30% greater risk of fatal PC. These observational cohort studies enrolled 21,579 PC patients and confirmed the association of smoking with PC recurrence and mortality. In addition, Gutt et al. (2010) examined 434 patients, and they stated that current smokers and former smoker patients have a recurrence rate up to 5.2 and 2.9 times greater, respectively, than the rate of life-long non-smokers.

2.3.2.3 Diet

2.3.2.3.1 animal fat.

Lipids are macromolecules responsible for storing energy, signaling, and acting as structural components of cell membranes. Lipids are divided into two groups: fats and steroids. A high-fat diet has been linked to an increased risk of prostate, breast, and colon cancers, among other malignancies ( Bianka et al., 2020 ). Le Marchand et al., Mucci et al., Platz et al., and Pauwels et al. confirmed a positive correlation between animal fat consumption and high incidence and mortality of PC patients ( Pauwels.,2011 ).

The World Research Cancer and Fund (WCRF) study showed that consumption of <500 g of red meat per week (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61, 0.98) was negatively correlated with a high risk of PC. Several other studies evaluate the relationship between red meat consumption and PC. They indicated that men receiving more than five serving parts of meat per week had a higher risk to develop PC than men who eat less than 1 serving/week ( Aronson WJ et al., 2010 ). It is still not clear what are the underlying possible biological mechanisms between high-fat dietary intake and PC risks, but it is possible that high energy intake increases basal metabolism and enhances prostate carcinogenesis via androgen. ( Schultz C et al., 2011 ; Arab L et al., 2013 ).

2.3.2.3.2 Calcium and milk

As milk and dairy products are rich in fat and calcium, they may be involved in the process of tumorigenesis. A meta-analysis of 12 publications confirmed a significant correlation between the high dairy intake of milk and calcium (>2000 mg/day) and advanced-stage and high-grade prostate cancer ( Schultz C et al., 2011 ). Calcium plays a key role in prostate carcinogenesis by controlling PC cell growth and apoptosis ( Kathryn MW et al., 2015 ). The biological pathways in which calcium can alter prostate carcinogenesis are still not clear. However, it was shown that intracellular calcium pools can control PC cell growth and significantly decrease their susceptibility to apoptosis ( Kathryn MW et al., 2015 ).

3 Prostate cancer detection reviewed in Gulf regions

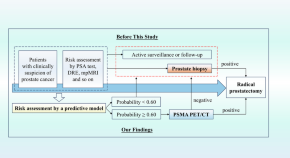

It is important to point out cancer in an early stage for the health of the patient and research society. Early detection of cancer makes treatment tremendously coherent. It can cause death because of poor diagnosis. Although tissue biopsy is the standard for diagnosis, the classification and recognition have improved via imaging and indicators or biomarkers ( Litwin et al., 2017 ). In this review, we have only explained in detail the detection of PC via machine learning as the conventional diagnostics have been explained previously in other research articles in detail.

By integrating machine learning and artificial intelligence in the research of prostate cancer early detection, thepositive and accurate result has increased. However, there are many challenges in the investigation process due to extremely high and low dataset samples. To improve the detection rate, the best feasible solution can be found using meta-heuristic algorithms.

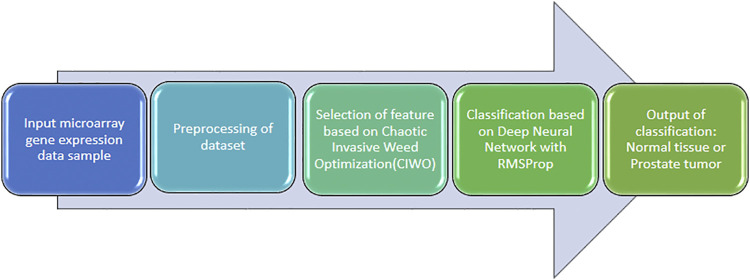

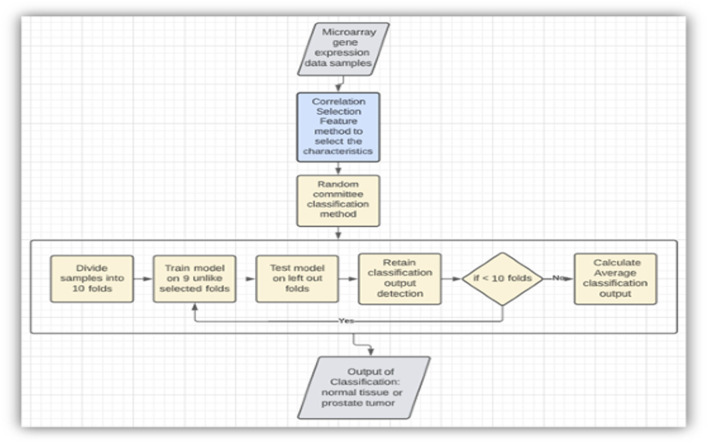

One of the approaches is by using a deep learning model for the detection of prostate cancer (AIFSDL-PCD) using a microarray gene expression dataset ( Figure 3 ). This approach used a feature selection technique “chaotic invasive weed optimization (CIWO)” after preprocessing data samples. Furthermore, a deep neural network (DNN) model with the RMSProp optimizer can be involved in prostate cancer detection. The output classification, as well as the analytical complicacy, is improved to a greater extent ( Abdul rhman M. et al., 2022 ).

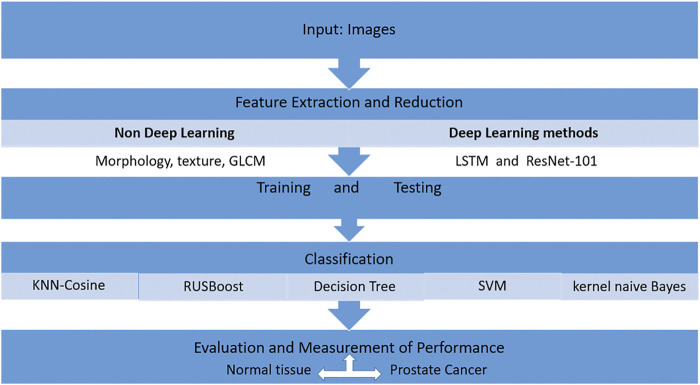

Deep learning methods such as long short-term memory (LSTM) and Residual Net (ResNet-101).

Traditional techniques such as support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), k-nearest neighbor-cosine (KNN-Cosine), RUSBoost tree, and kernel naive Bayes are unable to extricate the complicated characteristics of cancer. Other deep learning methods such as long short-term memory (LSTM) and Residual Net (ResNet-101) could be used as a better predictor for the detection of prostate cancer ( Figure 4 ). This approach compares the output of the deep learning methods and non-deep learning methods with the traditional feature extraction approach. First, the texture is extracted from a non-deep learning approach, and then, machine learning techniques are applied. The classification techniques are used, such as SVM, to detect prostate cancer. The highest detection is given by ResNet-101 based on its Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) function and an optimized gradient descent algorithm ( Saqib I et al., 2021 ).

Model using the correlation feature selection method and random committee model (RC).

As mentioned, to increase the rate of correctness and precision of detection, appropriate machine learning techniques are utilized. In one of the suggested approaches, as in Figure 5 , the input captured is a microarray dataset. By using the correlation feature selection method, the appropriate characteristics are selected. Then, by applying a random committee model (RC) to the input data, a few experiments are conducted using a 10-fold cross-validation technique for the evaluation of this current approach. This revealed a higher accuracy rate of output and increased the implementation time ( Abdu et al., 2021 ).

Age-standardized rate of patients with prostate cancer worldwide.

Experimental output is announced using some evaluation metrics such as the confusion matrix, precision, recall, specificity, F1-Score, and accuracy to show the efficiency of the proposed technique for prostate cancer detection. Also, the comparison results between these evaluation matrices confirmed the accuracy result as opposed to using all features.

4 Treatment of prostate cancer

Finalizing a treatment regime for the prostate cancer patient is determined keeping into consideration factors like the rate at which the cancer is growing, whether metastasis has set in, and most importantly implicated benefits and side effects of the treatment methods to be undertaken. The choice of the treatment procedure also considers the factor of risk of death from other causes. The conventional therapies for prostate cancer are chemotherapy and novel hormone therapies.

Different conventional therapies for prostate cancer are

4.1 Chemotherapy

4.2 Novel hormone therapies

The chemotherapeutic route of treatment involves the usage of drugs like docetaxel, cabaxitaxel, and mitoxantrone. Docetaxel has been one of the most successful drugs to improve the overall survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Improvement in overall survival symptoms, prostate-specific antigen, and quality of life was seen in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients when treated with docetaxel and prednisolone. Typically, docetaxel is administered intravenously every 3 weeks for recommended 10 cycles ( Litwin et al., 2017 ; He MH et al., 2018 ). The mode of action, although not fully understood but was observed to have targeted microtubules during mitosis and interphase, caused stabilization of the mitotic spindle leading to mitotic and cell proliferation arrest causing cell death. Cabaxitaxel is another approved chemotherapeutic drug, indicated for usage in the treatment of prostate cancer. Cabaxitaxel has got a similar mode of action to docetaxel where it disrupts microtubule function causing cell death. Cabaxitaxel is typically administered intravenously once every 3 weeks. Cabaxitaxel is also recommended for a 10-cycle regime, keeping in view the condition of the patient ( Qin et al., 2017 ).

4.2 Novel hormone therapy

The most widely used treatment route in treating metastatic prostate cancer was the process of castration which was followed for nearly a century. The treatment management involving castration came up with a success rate of 60%–70% depending on different criteria. A decrease in the success rate was observed with an increase in the secretion of adrenal androgen hormones in association with the evolution of upregulated or mutated androgen receptors ( Qin W et al., 2017 ; Omabe K et al., 2021 ). At the developmental stage, prostate cancer relies on the androgenic hormones to proliferate. A logical route to arresting the progression of prostate cancer is by lowering the levels of androgen hormones or blocking the androgenic action. The different types of hormonal therapy for prostate cancer are

a. Bilateral orchiectomy: nearly a century ago, this mode of treatment for prostate cancer was introduced involving the removal of both the testicles. This is quite a systematic way of treatment as it removes the source of testosterone production ( Litwin et al., 2017 ).

b. LHRH agonists: LHRH agonist or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist are medications that restrict the testicles from producing testosterone. The only difference between the LHRH agonist treatment method with orchiectomy is that the effects of LHRH agonists are found to be reversible, reliving the testosterone production soon after the treatment stops.

c. LHRH antagonists: LHRH antagonists are a class of drugs, known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists, which initiate the inhibition of the testosterone-like LHRH agonists by the testicles at a much faster pace devoid of the flare caused by the LHRH agonists. The FDA has approved an injectable drug called degarelix (Firmagon), administered monthly, for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer; on the contrary, it may cause severe allergic reactions. The FDA has also approved an oral LHRH antagonist, known as relugolix (Orgovyx), for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer.

d. Androgen synthesis inhibitors: there are other parts of the body like the adrenal gland other than the testicles which produce testosterone that can fuel the prostate cancer cells. Thus, androgen synthesis inhibitors are molecules that target an enzyme called CYP17 and resist cells from synthesizing testosterone. Examples of androgen synthesis inhibitors are abiraterone acetate and ketoconazole ( Litwin et al., 2017 ).

5 Role of nanoparticles in prostate cancer treatment

The conventional way of treating prostate cancer faced several challenges like depleted accumulation levels, faster clearance, or drug resistance at the tumor site. These factors led to the decline in effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs. Problems like decreased bioavailability and nonspecific distribution with severe side effects in delivery of anticancer drugs have been resolved by nanomedications like metallic nanoparticles and liposomes etc., that improve the therapeutic index with reduced non-specific distribution and higher dose of drugs ( Sanna V et al., 2012 ). The world of nanotechnology has opened a new avenue for the more advanced treatment of prostate cancer. Nanoparticles are remarkably efficient carriers of different therapeutic biomolecules by virtue of their unique size, large surface-to-volume ratio drug encapsulation capability, and modifiable surface chemistry ( Thakur A et al., 2021 ). For decades, common chemotherapeutic agents, like docetaxel and paclitaxel, were employed for the treatment of prostate cancer, which had disadvantages like non-selectivity toward cancerous tissues, thus causing injuries to the surrounding normal tissues, resulting in the lower therapeutic index and increased drug resistance. These were initial motivations behind developing newer ways of addressing an age-old problem ( Qin W et al., 2017 ). Nanotechnology emerges as a boon as it has the potential to address numerous issues that hinder the success of cancer therapy. Some of the issues that get better solutions by the application of nanoparticles are 1) enhanced delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs, 2) site-directed delivery of drugs toward specific biological and molecular targets, 3) development of innovative diagnostic tools, and 4) combination of therapeutic agents with diagnostic probes ( Thakur et al., 2021 ). Nanoparticle-facilitated molecular targeted therapy for cancer is a strategy of considerable promise which received astounding success in minimizing non-specific biodistribution and therapeutic index of traditional chemotherapeutic drugs. In recent times, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-conjugated nanoparticles have proved to be a potent management option for prostate cancer. This gives rise to better selectivity of drugs so that only diseased cells are targeted rather than normal ones ( Cherian AM et al., 2014 ). Epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCG), a natural product isolated from green tea, has been observed to possess potential chemo-preventive effects in both in vivo and in vitro models of prostate cancer. Modern cancer treatment approaches have now been catered to by the introduction of nanoparticle-mediated targeted drugs ( Litwin et al., 2017 ; Thakur et al., 2021 ). To put this in perspective, utilization of nanographene oxide (NGO) has increased many folds over the past decades since the quality of both side’s graphitic domains persists for drug loading due to the presence of hydrophobic interaction, π-π staking, and hydrogen bonding in their structure. Nanotechnology has been put to test for decades now to study treatment procedures for different kinds of cancer. The main focuses which help the popularity of nanotechnology to flourish are targeting tumors, elevated bioavailability, and reduced cytotoxicity ( Sanna V et al., 2012 ). Achieving specificity toward target cells, diminishing systemic toxicity, and attaining in vivo stability are some of the limitations that are considered while choosing nano delivery systems for the treatment of prostate cancer. To address the limitations, the budding application of aptamer-based targeted nano delivery and extracellular-mediated vesicle-mediated drug delivery turned out to be a very successful option. In addition to the specific delivery of siRNA and miRNA to cancer cells to achieve genetic silencing, which is a part of RNA nanotechnology, this could lead to efficient inhibition of prostate cancer. Aptamers are typically single-stranded oligonucleotides of 20–60 nucleotide length, possessing the capacity to bind to different molecules with specificity. Aptamers act like antibodies with the advantage of easier production methods at a low cost. A range of aptamer-based nano-carrier has been constructed for the effective delivery of drugs for the treatment of prostate cancer which enhanced tumor targeting. One of the initial aptamer-based nano delivery methodologies, PSMA aptamer/polo-like kinase 1(Plk1)-siRNA (A10-Plk1) chimera was established, which inhibited the growth of a prostate tumor. Thereafter, the second generation of PSMA-Plk1 chimeras was established to augment specificity and gene-specific silencing, thereby facilitating the upliftment of in vivo kinetics ( Thakur A et al., 2021 ). Most significantly, it was observed that the second-generation chimeras restrained the growth and proliferation of prostate cancer cells at a lower concentration than the first generation. To date, 16 clinical trials of the use of nanoparticles in PC treatment were registered, of which five were completed, four terminated, one withdrawn, one active but not recruiting, and 5 still recruiting ( gov 2022 ).

6 Conclusion

Continual progress in the field of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment has enhanced clinicians’ capacity to grade patients by risk and prescribe medication based on cancer prognosis and patient preference. When compared to androgen restriction therapy, the first chemotherapy treatment can improve survival. Men with metastatic prostate cancer who are resistant to standard hormone therapy may benefit from abiraterone, enzalutamide, and other medicines. Methodologies involving nanomedicines exemplify significant advancements in the drug delivery research arena. In terms of potential or utility, the design and functionality of NP vary greatly. It is worth noting that improving the selectivity of an NP-based drug delivery system can be performed by surface engineering of a specific NP of interest. The selection of a suitable surface marker, on the other hand, is critical for targeted NP-based therapeutic delivery. Overall, nanotechnology-based drug delivery has been extremely fruitful for cancer therapy, including PC treatment, with numerous advantages (such as passive tumor accumulation, active tumor targeting, and transport across tissue barriers) and drawbacks (such as toxicity and organ damage).

Author contributions

SaB wrote the introduction, incidences, and epidemiology of prostate cancer; InN compiled the data and prepared the tables and figures along with manuscript preparation; IrN wrote the diagnostics of prostate cancer; SuB contributed to writing the treatment part, and NA helped in the analysis of all the data.

This research was financially supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia under Grant Number: AN000509.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Abdu G., Rachid S., Mabrook A., Hussain A., Ali E. (2021). Feature selection with ensemble learning for prostate cancer diagnosis from microarray gene expression. Health Inf. J. 27 (1–13), 1460458221989402. 10.1177/1460458221989402 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abdulaziz A., Abdelmoneim M. E., Shoaib A. K., Wala A. A., Abdullah H. A. (2019). Yield of prostate cancer screening at a community based clinic in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 40 (7), 681–686. 10.15537/smj.2019.7.24256 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abdullah B. A., Anfal M. A., Omar A. A., Munif S. A., Abdulaziz I. A., Abdullah H. A., et al. (2017). Epidemiology of senile prostatic enlargement among elderly men in Arar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Electron. Physician 9 (9), 5349–5353. 10.19082/5349 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abdulrhman M. A., Raed A., Mohammed A., Fadwa A., Radwa M., Ibrahim A., et al. 2022. Optimal deep learning enabled prostate cancer detection using microarray gene expression, J. Healthc. Eng., Volume 2022, 7364704 pages. 10.1155/2022/7364704 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Addo B. K., Wang S., Chung W., Jelinek J., Patierno S. R., Wang B. D., et al. (2010). Identification of differentially methylated genes in normal prostate tissues from african american and caucasian men. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 3539–3547. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3342 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Akaza H., Kanetake H., Tsukamoto T., Miyanaga N., Sakai H., Masumori N., et al. (2011). Efficacy and safety of dutasteride on prostate cancer risk reduction in asian men: The results from the REDUCE study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 41 (3), 417–423. 10.1093/jjco/hyq221 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Al-Abdin O. Z., Rabah D. M., Badr G., Kotb A., Aprikian A. (2013). Differences in prostate cancer detection between Canadian and Saudi populations. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 46, 539–545. 10.1590/1414-431X20132757 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ali A., Ashraf A., Sultan A., Mohammed A., Danny R., Shouki B., et al. (2018). Saudi Oncology Society and Saudi Urology Association combined clinical management guidelines for prostate cancer 2017. Urol. Ann. 10 (2), 138–145. 10.4103/UA.UA_177_17 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aljoharah M. A., Rasha A. A., Nora A. A., Amani S. A., Nasser F. B. (2018). The prevalence of cigarette smoking in Saudi Arabia in 2018. FDRSJ 1, 1658–8002. 10.32868/rsjv1i122 Safety and Risk assessment, ISSN [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arab L., Su J., Steck S. E., Ang A., Fontham E. T. H., Bensen J. T., et al. Adherence to world cancer research fund American Institute for cancer research lifestyle recommendations reduces prostate cancer aggressiveness among african and caucasian Americans. Nutr. Cancer. 2013;65:633–643. 42. 10.1080/01635581.2013.789540 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aronson W. J., Barnard R. J., Freedland S. J., Henning S., Elashoff D., Jardack P. M., et al. (2010). Growth inhibitory effect of low fat diet on prostate cancer cells: Results of a prospective, randomized dietary intervention trial in men with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 183, 345–350. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.104 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baird W. M., Hooven L. A., Mahadevan B. (2005). Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and mechanism of action. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 45 (2–3), 106–114. 10.1002/em.20095 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandar M. A. (2020). Prostate cancer in Saudi Arabia: Trends in incidence, morphological and epidemiological characteristics. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 8 (11), 3899–3904. 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20204559 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bianka B., Pawel J. W., Magdalena W. W. (2020). Dietary fat and cancer—which is good, which is bad, and the body of evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4114. 10.3390/ijms21114114 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boeing H. (2013). Obesity and cancer-the update 2013. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 27 (2), 219–227. 10.1016/j.beem.2013.04.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlo S., Teresa P., Giovanni R. (2019). Obesity and liver cancer. Ann. Hepatol. 18, 810–815. 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.07.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cherian A. M., Nair S. V., Lakshmanan V. K. (2014). The role of nanotechnology in prostate cancer theranostic applications. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 841–852. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chuan S., Li-Ping B., Zhen-Yu Q., Guo-Zhen H., Zhong W. (2014). Overweight, obesity and meningioma risk: A MetaAnalysis. plos one 9, 841. 10.1166/jnn.2014.9052 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chung K. M., Singh J., Lawres L., Dorans K. J., Garcia C., Burkhardt D. B., et al. (2020). Endocrine-exocrine signaling drives obesity-associated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell 181 (4), 832–847.e18. e18. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.062 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Darst B. F., Wan P., Sheng X., Jeannette T. B., Sue A. I., Benjamin A. R., et al. (2020). A germline variant at 8q24 contributes to familial clustering of prostate cancer in men of African ancestry. Eur. Urol. 78, 316–320. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.060 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeSantis C. E., Siegel R. L., Sauer A. G., Kimberly D. M., Stacey A. F., Kassandra I. A., et al. (2016). Cancer statistics for african Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 66, 290–308. 10.3322/caac.21340 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlader N., Noone A. M., Krapcho M., Miller D., Bishop K., Altekruse S. F., et al. (2013). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2010 (Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; ) (based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER Web site. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gayathri S., Saba W. M., Tilahun A., Viswanathan R., John D. R. (2010). Association between family history of cancers and risk of prostate cancer. J. Men's. Health 7, 45–54. 10.1016/j.jomh.2009.10.006 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- GLOBOCAN (2020). Global cancer statistics. Switzerland: GLOBOCAN. [ Google Scholar ]

- gov C. (2022). Prostate cancer and nanoparticles. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Prostate+Cancer&term=nanoparticles .

- Gutt R., Tonlaar N., Kunnavakkam R., Karrison T., Weichselbaum R. R., Liauw S. L. (2010). Statin use and risk of prostate cancer recurrence in men treated with radiation therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 2653–2659. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hao Q., Zhijuan L., Elizabeth V., Xiao L., Feifei G., Xu L. (2021). Association between obesity and the risk of uterine fibroids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 75 (2), 197–204. 10.1136/jech-2019-213364 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- He M. H., Chen L., Zheng T., Ju Y., He Q., Fu H. L., et al. (2018). Potential applications of nanotechnology in urological cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 9 (745). 10.3389/fphar.2018.00745 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huncharek M., Haddock S., Reid R., Kupelnick B. (2010). Smoking as a risk factor for prostate cancer:A metaanalysis of 24 prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Public Health 100, 693–701. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150508 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jabril R. J., Leanne W. B., Stanley E. H., Ken B., Rick A. K. (2021). Genetic contributions to prostate cancer disparities in men of West African descent. Front. Oncol. 11, 770500. 10.3389/fonc.2021.770500 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacek K., Beata B. K., Rafał S., Edyta P., Katarzyna G. E., Agnieszka D. (2019). Obesity and the risk of gastrointestinal cancers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 64 (10), 2740–2749. 10.1007/s10620-019-05603-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jayadevappa R., Chhatre S., Johnson J. C., Malkowicz S. B. (2011). Association between ethnicity and prostate cancer outcomes across hospital and surgeon volume groups. Health Policy 99, 97–106. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.014 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jun T. Z., Jamil S., Kevin A. N., Michael S. L., Neeraj A., Karina B., et al. (2018). Genetic testing for hereditary prostate cancer: Current status and limitations. Cancer. 10.1002/cncr.31316 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kathryn M. W., Irene M. S., Lorelei A. M., Edward G. (2015). Calcium and phosphorus intake and prostate cancer risk: A 24-y follow-up study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101 (1), 173–183. 10.3945/ajcn.114.088716 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kyuwan L., Laura K., Christina M. D. C., Joanne E. M. (2019). The impact of obesity on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 21, 41. 10.1007/s11912-019-0787-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larsson S. C., Wolk A. (2007). Obesity and the risk of gallbladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 96, pages1457–1461. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603703 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larsson S. C., Wolk A. (2007). Body mass index and risk of multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 121 (11), 2512–2516. 10.1002/ijc.22968 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li J., Thompson T., Joseph A. D., Master V. A. (2012). Association between smoking status, and free, total and percent free prostate specific antigen. J. Urol. 187, 1228–1233. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.086 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Litwin M. S., Tan H. (2017). The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: A review. JAMA 317 (24), 2532–2542. 10.1001/jama.2017.7248 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maria T. V., Giovanna D. E., Gemma C., Marianna R., Amelia C., Passariello L., et al. (2021). Hereditary prostate cancer: Genes related, target therapy and prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (7), 3753. 10.3390/ijms22073753 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mauricio A. C., Sumie K., Francisca L. (2018). The impact on high-grade serous ovarian cancer of obesity and lipid metabolism-related gene expression patterns: The underestimated driving force affecting prognosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22 (3), 1805–1815. 10.1111/jcmm.13463 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meng-Bo H., Hua X., Pei-De B., Hao-Wen J., Qiang D. (2014). Obesity has multifaceted impact on biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer: A dose–response meta-analysis of 36, 927 patients. Med. Oncol. 31, 829. Article number: 829. 10.1007/s12032-013-0829-8 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Michael H., Haddock K. S., Reid R., Bruce K. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies American journal of public health april. Smok. as a Risk Factor Prostate Cancer 100, 4. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150508 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nair S. S., Chakravarty D., Dovey Z. S., Zhang X., Tewari A. K. (2022). Why do African-American men face higher risks for lethal prostate cancer? Curr. Opin. Urol. 32 (1), 96–101. 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000951 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Narayanan N. K., Nargi D., Randolph C., Narayanan B. A. (2009). Liposome encapsulation of curcumin and resveratrol in combination reduces prostate cancer incidence in PTEN knockout mice. Int. J. Cancer 125 (1), 1–8. 10.1002/ijc.24336 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Omabe K., Paris C., Lannes F., Taïeb D., Rocchi P. (2021). Nanovectorization of prostate cancer treatment strategies: A new approach to improved outcomes. Pharmaceutics 13, 591. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13050591 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Osman Z. A., Ibrahim Z. A. (2018). Prostate cancer in the Arab population. An overview. Saudi Med. J. 39 (5), 453–458. 10.15537/smj.2018.5.21986 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Panigrahi G. K., Praharaj P. P., Kittaka H., Mridha A. R., Black O. M., Singh R., et al. (2019). Exosome proteomic analyses identify inflammatory phenotype and novel biomarkers in African American prostate cancer patients. Cancer Med. 8 (3), 1110–1123. 10.1002/cam4.1885 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pauwels E. K. (2011). The protective effect of the mediterranean diet: Focus on cancer and cardiovascular risk. Med. Princ. Pract. 20, 103–111. 10.1159/000321197 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pavel C., Victoria M. K., Ahmedin J., Mark P. L., Philip S. R. (2018). Heterogeneity of colon and rectum cancer incidence across 612 SEER counties. Cancer Epidemiol. First Publ. 27, 2000–2014. 10.1002/ijc.31776 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perdana N. R., Mochtar C. A., Umbas R., Hamid A. R. (2016). The risk factors of prostate cancer and its prevention: A literature review. Acta Med. Indones. 48 (3), 228–238. PMID: 27840359. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powell I. J., Fischer A. B. (2013). Minireview: The molecular and genomic basis for prostate cancer health disparities. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 879–891. 10.1210/me.2013-1039 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prashanth R., Krishna C. T., Tagore S. (2019). Pancreatic cancer and obesity: Epidemiology, mechanism, and preventive strategies. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 12, pages285–291. 10.1007/s12328-019-00953-3 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qin W., Zheng Y., Qian B. Z., Zhao M. (2017). Prostate cancer stem cells and nanotechnology: A focus on wnt signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 8 (153). 10.3389/fphar.2017.00153 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rebello R. J., Oing C., Knudsen K. E., Loeb S., Johnson D. C., Reiter R. E., et al. (2021). Prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 7, 9. 10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross-Adams H., Lamb A. D., Dunning M. J., Halim S., Lindberg J., Massie C. M., et al. (2015). Integration of copy number and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: A discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine 2, 1133–1156. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.017 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanna L. C., Wolk A. (2007). Body mass index and risk of multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 121 (11), 2512–2516. 10.1002/ijc.22968 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanna L. C., Wolk A. (2007). Obesity and the risk of gallbladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 96, 1457–1461. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603703 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanna V., Sechi M. (2012). Nanoparticle therapeutics for prostate cancer treatment. Maturitas 73, 27–32. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.016 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saqib I., Ghazanfar F. S., Amjad R., Lal H., Tanzila S., Usman T., et al. (2021). Prostate cancer detection using deep learning and traditional techniques. IEEE Access 9, 27085–27100. 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3057654 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schultz C., Meier M., Schmid H. P. (2011). Nutrition, dietary supplements and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Maturitas 70, 339–342. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.08.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shin G. H., Chung S. K., Kim J. T., Joung H. J., Park H. J. (2013). Preparation of chitosan-coated nanoliposomes for improving the mucoadhesive property of curcumin using the ethanol injection method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 (46), 11119–11126. 10.1021/jf4035404 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. (2018). Cancer statistics, 2018. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 68, 7–30. 10.3322/caac.21442 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thakur A. (2021). Nano therapeutic approaches to combat progression of metastatic prostate cancer. Adv. Cancer Biol. - Metastasis 2, 100009. 10.1016/j.adcanc.2021.100009 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Theodora P., Maria A. (2014). Obesity and thyroid cancer: A clinical update ThyroidVol. Rev. Sch. Dialog Open Access 24, 2. 10.1089/thy.2013.0232 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tian Y. (2014). Inhibitory effect of curcumin liposomes on PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. Chin. J. Exp. Surg. 31 (5), 1075–1078. 10.3760/CMA.J.ISSN.1001-9030.2014.05.053 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Travis R. C., Appleby P. N., Martin R. M., Holly J. M. P., Albanes D., Black A., et al. (2016). A meta-analysis of individual participant data reveals an association between circulating levels of IGF-I and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 76, 2288–2300. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1551 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vickers A. J., Cronin A. M., Bjork T., Manjer J., Nilsson P. M., Dahlin A., et al. (2010). Prostate specific antigen concentration at age 60 and death or metastasis from prostate cancer: Case-control study. BMJ 341, c4521–8. 10.1136/bmj.c4521 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu I., Modlin C. S. (2012). Disparities in prostate cancer in african-American men: What primary care physicians can do. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 79, 313–320. 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhen J. T., Syed J., Nguyen K. A., Leapman M. S., Agarwal N., Brierley K., et al. (2018). Genetic testing for hereditary prostate cancer: Current status and limitations. Cancer 124, 3105–3117. 10.1002/cncr.31316 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.5 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Prostate cancer articles from across Nature Portfolio

Prostate cancer is a type of malignancy that arises in the prostate gland. Prostate cancer tends to develop in older men, aged 50 and over. In many cases prostate cancer develops slowly, although in some cases it can be aggressive and metastasize to other parts of the body.

Latest Research and Reviews

Survival outcomes of apalutamide as a starting treatment: impact in real-world patients with metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer (OASIS)

- Benjamin L. Maughan

- Yanfang Liu

- Lawrence I. Karsh

Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy for radio-recurrent prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Jianjiang Liu

A TBX2-driven signaling switch from androgen receptor to glucocorticoid receptor confers therapeutic resistance in prostate cancer

- Sayanika Dutta

- Hamed Khedmatgozar

- Srinivas Nandana

Radical prostatectomy without prostate biopsy based on a noninvasive diagnostic strategy: a prospective single-center study

- Changming Wang

Mitochondrial unfolded protein response-dependent β-catenin signaling promotes neuroendocrine prostate cancer

- Jordan Alyse Woytash

- Rahul Kumar

- Dhyan Chandra

Canonical androgen response element motifs are tumor suppressive regulatory elements in the prostate

Androgen response elements (AREs) regulation produce opposite effects in normal and cancer prostate cells. Here, authors engineer a modifier of ARE-containing chromatin (MACC) to define the elements responsible for a normal growth-suppressive program, which can be reengaged in prostate cancer cells.

- Xuanrong Chen

- Michael A. Augello

- Christopher E. Barbieri

News and Comment

Personalized 3d models for prostate cancer surgery.

- Maria Chiara Masone

PEACEing together prostate cancer therapy

- Louise Lloyd

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy haemostasis techniques and outcomes

The robot-assisted approach to radical prostatectomy has enabled same-day discharge. A substantial concern associated with this practice could be haemorrhage, but sound and thorough robot-assisted radical prostatectomy haemostasis surgical techniques that were introduced to prevent bleeding mitigate this phenomenon.

- Joshua Winograd

Tomorrow’s patient management: LLMs empowered by external tools

Large language models are gaining increasing interest in the medical community; however, an important but overlooked aspect of their capacity is their ability to integrate with tools. This integration greatly extends their potential application in health care.

- Kelvin Szolnoky

- Tobias Nordström

- Martin Eklund

177 Lu-PSMA-617 extends progression-free survival in taxane-naive mCRPC

Mri-based stratification reduces the risk of overdiagnosis of prostate cancer.

- Peter Sidaway

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are research studies that involve people. The clinical trials on this list are for prostate cancer. All trials on the list are NCI-supported clinical trials, which are sponsored or otherwise financially supported by NCI.

NCI’s basic information about clinical trials explains the types and phases of trials and how they are carried out. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. You may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Talk to your doctor for help in deciding if one is right for you.

This phase III trial compares less intense hormone therapy and radiation therapy to usual hormone therapy and radiation therapy in treating patients with high risk prostate cancer and low gene risk score. This trial also compares more intense hormone therapy and radiation therapy to usual hormone therapy and radiation therapy in patients with high risk prostate cancer and high gene risk score. Apalutamide may help fight prostate cancer by blocking the use of androgen by the tumor cells. Radiation therapy uses high energy rays to kill tumor cells and shrink tumors. Giving a shorter hormone therapy treatment may work the same at controlling prostate cancer compared to the usual 24 month hormone therapy treatment in patients with low gene risk score. Adding apalutamide to the usual treatment may increase the length of time without prostate cancer spreading as compared to the usual treatment in patients with high gene risk score.

This phase III trial compare the effects of adding definitive treatment (either radiation therapy or prostate removal surgery) to standard systemic therapy in treating patients with prostate cancer that has spread to other places in the body (advanced). Removing the prostate by either surgery or radiation therapy in addition to standard systemic therapy for prostate cancer may lower the chance of the cancer growing or spreading.

This phase III trial studies whether adding apalutamide to the usual treatment improves outcome in patients with lymph node positive prostate cancer after surgery. Radiation therapy uses high energy x-ray to kill tumor cells and shrink tumors. Androgens, or male sex hormones, can cause the growth of prostate cancer cells. Drugs, such as apalutamide, may help stop or reduce the growth of prostate cancer cell growth by blocking the attachment of androgen to its receptors on cancer cells, a mechanism similar to stopping the entrance of a key into its lock. Adding apalutamide to the usual hormone therapy and radiation therapy after surgery may stabilize prostate cancer and prevent it from spreading and extend time without disease spreading compared to the usual approach.

This phase III trial tests two questions by two separate comparisons of therapies. The first question is whether enhanced therapy (apalutamide in combination with abiraterone + prednisone) added to standard of care (prostate radiation therapy and short term androgen deprivation) is more effective compared to standard of care alone in patients with prostate cancer who experience biochemical recurrence (a rise in the blood level of prostate specific antigen [PSA] after surgical removal of the prostate cancer). A second question tests treatment in patients with biochemical recurrence who show prostate cancer spreading outside the pelvis (metastasis) by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. In these patients, the benefit of adding metastasis-directed radiation to enhanced therapy (apalutamide in combination with abiraterone + prednisone) is tested. Diagnostic procedures, such as PET, may help doctors look for cancer that has spread to the pelvis. Androgens are hormones that may cause the growth of prostate cancer cells. Apalutamide may help fight prostate cancer by blocking the use of androgens by the tumor cells. Metastasis-directed targeted radiation therapy uses high energy rays to kill tumor cells and shrink tumors that have spread. This trial may help doctors determine if using PET results to deliver more tailored treatment (i.e., adding apalutamide, with or without targeted radiation therapy, to standard of care treatment) works better than standard of care treatment alone in patients with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer.

This phase II trial studies how well cabozantinib works in combination with nivolumab and ipilimumab in treating patients with rare genitourinary (GU) tumors that has spread from where it first started (primary site) to other places in the body. Cabozantinib may stop the growth of tumor cells by blocking some of the enzymes needed for cell growth. Immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies, such as nivolumab and ipilimumab, may help the body's immune system attack the cancer, and may interfere with the ability of tumor cells to grow and spread. Giving cabozantinib, nivolumab, and ipilimumab may work better in treating patients with genitourinary tumors that have no treatment options compared to giving cabozantinib, nivolumab, or ipilimumab alone.

This phase III trial compares stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), (five treatments over two weeks using a higher dose per treatment) to usual radiation therapy (20 to 45 treatments over 4 to 9 weeks) for the treatment of high-risk prostate cancer. SBRT uses special equipment to position a patient and deliver radiation to tumors with high precision. This method may kill tumor cells with fewer doses over a shorter period of time. This trial is evaluating if shorter duration radiation prevents cancer from coming back as well as the usual radiation treatment.

This phase III trial compares the effect of adding carboplatin to the standard of care chemotherapy drug cabazitaxel versus cabazitaxel alone in treating prostate cancer that keeps growing even when the amount of testosterone in the body is reduced to very low levels (castrate-resistant) and that has spread from where it first started (primary site) to other places in the body (metastatic). Carboplatin is in a class of medications known as platinum-containing compounds. Carboplatin works by killing, stopping or slowing the growth of tumor cells. Chemotherapy drugs, such as cabazitaxel, work in different ways to stop the growth of tumor cells, either by killing the cells, by stopping them from dividing, or by stopping them from spreading. Prednisone is often given together with chemotherapy drugs. Prednisone is in a class of medications called corticosteroids. It is used to reduce inflammation and lower the body's immune response to help lessen the side effects of chemotherapy drugs and to help the chemotherapy work. Giving carboplatin with the standard of care chemotherapy drug cabazitaxel may be better at treating metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

This phase II trial tests how well carboplatin before surgery works in treating patients with high-risk prostate cancer who have inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations. This study selects a patient population in which carboplatin is more likely to work. The purpose of the study is to treat men with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who are at higher risk of prostate cancer after surgery (removal of the prostate) compared to patients without these mutations. Carboplatin works in a way similar to the anticancer drug cisplatin, but may be better tolerated than cisplatin. Carboplatin works by killing, stopping, or slowing the growth of tumor cells. Giving carboplatin before surgery may shrink tumor in patients with high-risk prostate cancer who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

This phase II trial compares the usual treatment of radiation therapy alone to using the study drug, relugolix, plus the usual radiation therapy in patients with castration-sensitive prostate cancer that has spread to limited other parts of the body (oligometastatic). Relugolix is in a class of medications called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonists. It works by decreasing the amount of testosterone (a male hormone) produced by the body. It may stop the growth of cancer cells that need testosterone to grow. Radiation therapy uses high-energy x rays or protons to kill tumor cells. The addition of relugolix to the radiation may reduce the chance of oligometastatic prostate cancer spreading further.

This phase III trial studies docetaxel and radium Ra 223 dichloride to see how well it works compared with docetaxel alone in treating patients with prostate cancer that has spread to other places in the body, despite the surgical removal of the testes or medical intervention to block androgen production (metastatic castration-resistant). Chemotherapy drugs, such as docetaxel, work in different ways to stop the growth of tumor cells, either by killing the cells, by stopping them from dividing, or by stopping them from spreading. Radium Ra 223 dichloride is a radioactive drug that is given through the vein and is taken up by bones after it is injected into the body. Radioactive drugs work by giving off energy, which is thought to kill the tumor cells and other cells that support the tumor cells after the cancer has spread to the bone. It is not known whether docetaxel with or without radium Ra 223 dichloride works better at treating metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

This randomized phase II trial studies how well surgical removal of the prostate and antiandrogen therapy with or without docetaxel work in treating men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer that has spread to other places in the body. Androgens can cause the growth of prostate cancer cells. Antiandrogen therapy may lessen the amount of androgens made by the body. Drugs used in chemotherapy, such as docetaxel work in different ways to stop the growth of tumor cells, either by killing the cells, by stopping them from dividing, or by stopping them from spreading. Surgery, antiandrogen therapy and docetaxel may work better in treating participants with prostate cancer.

The intention of the study is to demonstrate superiority of Saruparib (AZD5305) + physician's choice NHA relative to placebo + physician's choice NHA by assessment of radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) in participants with mCSPC.

This is a multicenter Phase 1b, open label, dose-escalation and cohort-expansion study, evaluating the safety, tolerability, PK, preliminary antitumor activity, and effect of biomarkers of XL092 administered alone, and in combination with nivolumab (doublet), nivolumab + ipilimumab (triplet) and nivolumab + relatlimab (triplet) in subjects with advanced solid tumors. In the Expansion Stage, the safety and efficacy of XL092 as monotherapy and in combination therapy will be further evaluated in tumor-specific Expansion Cohorts.

The purpose of this study is to assess the efficacy and safety of opevesostat plus hormone replacement therapy (HRT) compared to alternative abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide in participants with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) previously treated with one next-generation hormonal agent (NHA). The primary study hypotheses are that opevesostat is superior to alternative abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide with respect to radiographic progression free survival (rPFS) per Prostate Cancer Working Group (PCWG) Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1) as assessed by Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR) and overall survival (OS), in androgen receptor ligand binding domain (AR LBD) mutation positive and negative participants.

This phase I/II trial studies the best dose of M3814 when given together with radium-223 dichloride or with radium-223 dichloride and avelumab and to see how well they work in treating patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer that had spread to other places in the body (metastatic). M3814 may stop the growth of tumor cells by blocking some of the enzymes needed for cell growth. Radioactive drugs, such as radium-223 dichloride, may carry radiation directly to tumor cells and not harm normal cells. Immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies, such as avelumab, may help the body’s immune system attack the cancer, and may interfere with the ability of tumor cells to grow and spread. This study is being done to find out the better treatment between radium-223 dichloride alone, radium-223 dichloride in combination with M3814, or radium-223 dichloride in combination with both M3814 and avelumab, to lower the chance of prostate cancer growing or spreading in the bone, and if this approach is better or worse than the usual approach for advanced prostate cancer not responsive to hormonal therapy.

Evaluate the safety and tolerability of AMG 509 in adult participants and determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) or recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D).