Distinguishing Between Case Studies & Experiments

Case Study vs Experiment

Case studies and experiments are two distinct research methods used across various disciplines, providing researchers with the ability to study and analyze a subject through different approaches. This variety in research methods allows the researcher to gather both qualitative and quantitative data, cross-check the data, and assign greater validity to the conclusions and overall findings of the research. A case study is a research method in which the researcher explores the subject in depth, while an experiment is a research method where two specific groups or variables are used to test a hypothesis. This article will examine the differences between case study and experiment further.

What is a Case Study?

A case study is a research method where an individual, event, or significant place is studied in depth. In the case of an individual, the researcher studies the person’s life history, which can include important days or special experiences. The case study method is used in various social sciences such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology. Through a case study, the researcher can identify and understand the subjective experiences of an individual regarding a specific topic. For example, a researcher studying the impact of second rape on the lives of rape victims can conduct several case studies to understand the subjective experiences of individuals and social mechanisms that contribute to this phenomenon. The case study is a qualitative research method that can be subjective.

What is an Experiment?

An experiment, unlike a case study, can be classified as a quantitative research method, as it provides statistically significant data and an objective, empirical approach. Experiments are primarily used in natural sciences, as they allow the scientist to control variables. In social sciences, controlling variables can be challenging and may lead to faulty conclusions. In an experiment, there are mainly two variables: the independent variable and the dependent variable. The researcher tries to test their hypothesis by manipulating these variables. There are different types of experiments, such as laboratory experiments (conducted in laboratories where conditions can be strictly controlled) and natural experiments (which take place in real-life settings). As seen, case study methods and experiments are very different from one another. However, most researchers prefer to use triangulation when conducting research to minimize biases.

Key Takeaways

- Case studies are in-depth explorations of a subject, providing qualitative data, while experiments test hypotheses by manipulating variables, providing quantitative data.

- Experiments are primarily used in natural sciences, whereas case studies are primarily used in social sciences.

- Experiments involve testing the correlation between two variables (independent and dependent), while case studies focus on exploring a subject in depth without testing correlations between variables.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Articles

Difference between power & authority, distinguishing could of & could have, distinguishing pixie & bob haircuts, distinguishing between debate & discussion, distinguishing between dialogue & conversation, distinguishing between a present & a gift, distinguishing between will & can, distinguishing between up & upon.

Case Study vs Experiment: Know the Difference

A case study and experiment are the two prominent approaches often used at the forefront of scholarly inquiry. While case studies study the complexities of real-life situations, aiming for depth and contextual understanding, experiments seek to uncover causal relationships through controlled manipulation and observation. Both these research methods are indispensable tools in understanding phenomena, yet they diverge significantly in their approaches, aims, and applications.

In this article, we’ll unpack the key differences between case studies and experiments, exploring their strengths, limitations, and the unique insights they offer when working with quantitative data. In the meantime, feel free to use our specialized case study writing service if you seek to streamline your efforts when handling this academic task.

What Is a Case Study?

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination of a particular individual, group, event, or phenomenon within its real-life context. It aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the subject under investigation, often using multiple data sources such as interviews, observations, documents, and archival records.

The case study method is used in psychology, sociology, anthropology, education, and business to explore complex issues, understand unique situations, and generate rich, contextualized insights. They allow scholars to explore the intricacies of real-world phenomena, uncovering patterns, relationships, and underlying factors in social sciences that may not be readily apparent through other research methods.

Overall, case studies offer a holistic and nuanced understanding of the subject of interest, facilitating deeper exploration and interpretation of complex social and human phenomena. If you’re struggling with this assignment, simply say, ‘ write my case study for me ,’ and our experts will help you promptly.

What Is an Experiment?

Compared to the case study method, an experiment investigates cause-and-effect relationships by systematically manipulating one or more variables and observing the effects on other variables. In an experiment, students aim to establish causal relationships between an independent variable (the factors being manipulated) and a dependent variable (the outcomes being measured).

Experiments are characterized by their controlled and systematic approach, often involving the random assignment of participants to different experimental conditions to minimize bias and ensure the validity of the findings. They are commonly used in such fields of social sciences as psychology, biology, physics, and medicine to test hypotheses, identify causal mechanisms, and provide empirical evidence for theories.

An experiment method allows scholars to establish causal relationships with high confidence, providing valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of behavior, natural phenomena, and social processes. Other research methods include:

- Survey method: Collects research data from individuals through questionnaires or interviews to gather information about attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and characteristics of a population.

- Observation method: Systematically observes and records behavior, events, or phenomena as they naturally occur in real-life settings to study social interactions, environmental factors, or naturalistic behavior.

- Qualitative and quantitative research method: Qualitative research explores meanings, perceptions, and experiences using interviews or content analysis, while quantitative research analyzes numerical data to test hypotheses or identify patterns and relationships.

- Archival research method: Analyzes existing documents, records, or data sources such as historical documents or organizational archives to investigate trends, patterns, or historical events.

- Action research method: Involves collaboration between scholars and practitioners to identify and address practical problems or challenges within specific organizational or community contexts, aiming to generate actionable knowledge and facilitate positive change.

Difference Between Case Study and Experiment

Case study and experiment definitions.

A case study method involves a deep investigation into a specific individual, group, event, or phenomenon within its real-life context, aiming to provide rich and detailed insights into complex issues. Learners gather research data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and archival records, to comprehensively understand the subject under study.

Case studies are particularly useful for exploring unique or rare phenomena, offering a holistic view that captures the intricacies and nuances of the situation. However, findings from case studies may be challenging to generalize to broader populations due to the specificity of the case and the lack of experimental control. To learn more about how to write a case study , please refer to our guide.

An experiment is a research method that systematically manipulates one or more variables to observe their effects on other variables, aiming to establish cause-and-effect relationships under controlled conditions. Researchers design experiments with high control over variables, often using standardized procedures and quantitative measures for research data collection.

Experiments are well-suited for testing hypotheses and identifying causal relationships in controlled environments, allowing educatees to conclude the effects of specific interventions or manipulations. However, experiments may lack the depth and contextual richness of case studies, and findings are typically limited to the specific conditions of the experiment.

Case Study and Experiment Characteristic Features

- In case studies , variables are observed rather than manipulated. Researchers do not typically control variables; instead, they examine how naturally occurring variables interact within the case context.

- Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables to observe their effects on other variables. Students actively control and manipulate variables to test hypotheses and establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Case studies may not always begin with a specific hypothesis. Instead, researchers often seek to generate hypotheses based on the data collected during the study.

- Experiments are typically conducted to test specific hypotheses. Researchers formulate a hypothesis based on existing theory or observations, and the experiment is designed to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Manipulating Variables

- Variables are not manipulated in case studies . Instead, researchers observe and analyze how naturally occurring variables influence the phenomenon of interest.

- In experiments , researchers actively manipulate one independent or dependent variable or more to observe their effects on other variables. This manipulation allows researchers to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Case studies often involve collecting qualitative data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and archival records. Researchers analyze this research data to provide a detailed and contextualized understanding of the case.

- Experiments typically involve the collection of quantitative data using standardized procedures and measures. Researchers use statistical analysis to interpret the research data and draw conclusions about the effects of the manipulated variables.

Areas of Implementation

- Case studies are widely used in social sciences, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, education, and business, to explore complex issues, understand unique situations, and generate rich, contextualized insights.

- Experiments are common in fields such as psychology, biology, physics, and medicine, where researchers seek to test hypotheses, identify causal mechanisms, and provide empirical evidence for theories through controlled manipulation and observation.

Frequently asked questions

She was flawless! first time using a website like this, I've ordered article review and i totally adored it! grammar punctuation, content - everything was on point

This writer is my go to, because whenever I need someone who I can trust my task to - I hire Joy. She wrote almost every paper for me for the last 2 years

Term paper done up to a highest standard, no revisions, perfect communication. 10s across the board!!!!!!!

I send him instructions and that's it. my paper was done 10 hours later, no stupid questions, he nailed it.

Sometimes I wonder if Michael is secretly a professor because he literally knows everything. HE DID SO WELL THAT MY PROF SHOWED MY PAPER AS AN EXAMPLE. unbelievable, many thanks

New posts to your inbox!

Stay in touch

header text

- About/Contact

- Case Study Examples

- Case Studies Process

- Why Local Businesses?

- Online News Boosts

How a Case Study Differs from Other Types of Research

When it comes to research, there are a variety of methods used to acquire data and draw conclusions. Among them is the case study, which looks in depth at a single event or individual to gain insight into broader trends. But how does this approach differ from other types of research? In this blog post, we’ll explore the distinctions between case studies and other types of research — such as surveys and experiments — so that you can decide which method is best for your project.

Let’s start by defining what a case study is. A case study is an in-depth look at a specific event, person or situation in order to draw conclusions about broader trends or issues. It involves collecting qualitative (e.g., interviews) and quantitative (e.g., surveys) data from multiple sources and analyzing it to form an argument or hypothesis. Unlike some other types of research, case studies are not necessarily intended to be generalizable; rather, they are meant to provide insight into the particular subject being studied.

Case studies differ from other types of research in several ways:

They rely heavily on qualitative data: As mentioned above, one key distinction between a case study and other forms of research is that it relies heavily on qualitative data — such as interviews — rather than quantitative data like surveys or experiments. Qualitative data provides deeper insight into the subject being studied by delving into its complexities and nuances, which can often be missed by more structured forms of data collection like surveys or experiments.

They focus on a single event/person/situation: Another distinguishing feature of case studies is that they focus on studying one particular event/person/situation in depth rather than attempting to draw broad generalizations from multiple sources or cases. This allows researchers to gain insight into the dynamics at play within the particular context being studied, rather than attempting to make larger claims about similar events in different contexts without adequate evidence to support them.

They may not be generalizable: Finally, unlike some other forms of research that seek generalizable results applicable across multiple contexts (e.g., survey results), case studies may not necessarily have generalizability as their primary goal; instead, they seek deeper understanding through exploring details within the single context being studied itself.

When a case study is the best approach

Now that we’ve looked at what distinguishes a case study from other types of research let’s consider when it might be most appropriate for your project needs:

When you need an in-depth understanding: Case studies are particularly well suited for projects where an in-depth understanding of an individual person/event/situation is needed rather than broad generalizations about similar events across multiple contexts. For example, if you were researching how people interact with technology and wanted greater insight into how different users interact with specific software applications then conducting several detailed interviews with users would likely yield better results than conducting a survey across multiple populations where responses might be more generic due to lack of personal detail involved with each response given by participants .

When you need contextual information: Case studies are also useful when considering complex situations where contextual information may influence outcomes; for example if you wanted to understand how poverty affects access to education then looking at individual stories within certain communities could provide valuable insights that would otherwise be missed if only considering survey responses from those communities without any further exploration through interviews etc..

When you need rich narrative detail: Finally, if your project requires rich narrative detail — such as stories about peoples lives — then again conducting several detailed interviews would likely yield better results than simply surveying participants as these kinds of stories may not always come out through standard survey questions alone due to lack of personal engagement involved with completing them accurately etc.

In conclusion then while there are many similarities between various forms of research there are also important distinctions between them too – particularly when comparing something like a case study against something like surveys or experiments etc.. The key takeaway here though should be when deciding which method best suits your project needs consider carefully whether getting an ‘in-depth understanding’ , ‘contextual information’ , ‘rich narrative detail’ etc..are primary goals – then use this knowledge alongside others factors such as time available , budget constraints etc..to decide which method best fits your requirements overall .

You May Also Like

Should You Distribute a Press Release Before or After an Event?

Press Release Inspiration: Newsworthy Ideas for Local Businesses

Columbia MO Photographer Sarah Jane Shorthose Propelled to Top of Google by Press Release

Case Studies Blend Emotion and Logic to Increase Sales

Using Case Studies With Press Releases for Local Businesses

Winning Customers Without Competing on Price

Case studies vs Experiments

There are two different sources researchers get their information from. One is from experiments, where variables are added and taken away as the researchers wish, and the other is from case studies, which is the analysis of an instance that arose by itself.

There are as with everything pros and cons to both these sources.

Take for example Stanford’s prison experiment. Twenty four men were randomly selected, and then randomly split into the two groups of guards and prisoners. The experiment was abandoned 6 days in as the ‘officers’ began to abuse their authority and the participants started to drop out. This was an experiment. Therefore variables were controlled, participants were randomly selected and conditions were monitored. However even though this small group of the population acted this way, does it mean all the population would? Can it be generalised and it be said that all of us, if put in a position of authority would abuse that role? What about the real prison guards. In a real life situation authoritative roles have responsibility and apart from the odd few that authority is not abused. Maybe there were other variables that affected how those men behaved. Maybe one had been abused in early life and took the experiment as a way to release anger by inflicting abuse on someone else. Maybe eleven of the guards had personalities which made them easily influenced and the twelfth guard had an aggressive streak. Maybe if the men were left in those roles for longer they would have maintained a level of decency however the experiment had to be terminated due to ethical reasons.

On the other hand, take the case of Genie. Genie was a girl who spent the first thirteen years of her life locked in a bedroom and strapped to a potty chair where her only her father was allowed to talk to communicate with her and he would only growl and bark at her like a dog to keep her quiet. When genie was discovered she was mute had developed a characteristic “bunny walk” in which she held her hands up in front, like claws and constantly sniffed, spat, and clawed. She provided an excellent case for the study of linguistics and psychologists interested in child isolation and how we learn language at at later age. However Genie was just one child who was put in this situation. The variables were not controlled and Genie herself was not randomly selected. Maybe she was born with a mental disorder anyway that would have made her behave in some of the ways that was out down to be a cause of her isolation. Maybe if another child were put in such horrific circumstances they would have reacted very differently. Of course unless another case study such as Genie presents itself these questions will never be answered. And even if such a case arose, it would be very unlikely that the child’s treatment, environment or even gender would be the same. Obviously such a circumstance can not be replicated in an experiment as that would be unethical.

So basically, experiments give us more control over variables and a bigger subject size, but its limited by ethics and the inability to control all variables for a long period of time. Case studies are valuable as they are genuine and not limited by ethics but are rare to come across and hard to compare to other such cases as they are all very different.

I think its experiments that wins this one. No one (in theory) is harmed by its occurrence and variables can be better controlled.

Share this:

About libbyayres

4 responses to case studies vs experiments.

I would argue that both methods have definite benefits to the field of psychology. Whilst, as you said, lab experiments etc do provide a great deal of control to allow a researcher to distinguish between variables, without case studies we would not be able to understand certain things about human behaviour because they are unethical. Also if a case study brings to light certain new information, this can potentially lead to the development of new areas experimental research connected to the case study.

In my opinion, experiments provide more useful insight than case studies. As you’ve said, variables can be controlled and manipulated to provide and analyse results, and can go on to assist in the exploration of future hypotheses and experiments. With the Zimbardo experiment, it certainly gave us insight into the theory of deindividuation, where an individual takes on the personality or adapts their behaviour and decisions/opinions to that of a group of people i.e. they disregard their own beliefs in favour of the behaviour or opinions shown by the entire group. Deindividuation has been shown to have a significant on human behaviour, even to the extent shown by the prison guards in the Zimbardo experiment.

The best example of case studies I can think of are those used by Sigmund Freud during the era of the psychodynamic approach. These are mostly disregarded today due to the lack of scientific evidence to support his theories. Whilst this might not be the case with case studies, they may provide some useful insight to individual behaviour. But it is certainly the use of experiments with an adequately sized sample of participants with results that can be generalised to the population that really help in the progression of psychological research.

Both are very important for psychology and provide a different look, at either a hypothesis or a certain situation. However experiments provide a more natural setting even in a laboratory environment and allow the subjects to be viewed by the experimenter. This in comparison with the case studies which is an occurrence and the psychologist dealing with the situation after the incident. Ethics don’t play much of a part during the incident because the psychologist is unable to effect the outcome thus showing the positive side of case studies. Freud favoured these case studies despite his poor choice of candidates.

In my opinion both methods have great importance to the field of psychology. Experiments provide a great deal of control (Lab studies) and allow the research to be conducted in a much more natural environment (Field studies). Whereas case studies provide us with much more detailed and rich research about individuals, towards human behaviour. They allow us to focus on a particular area and study it in detail. Problems with this approach are that ethics don’t particularly play a part as with most case studies psychologists are ealing with the outcome of a situation after an incident has occurred. We are unable to effect the outcome thus highlighting a advantage to case studies. They are much more natural and give us a greater idea about the research. Of course what tends to happen, an example being Freud, is that the results of said research are generalised to the rest of the population which simply cannot be done.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

Recent Posts

- How Good Are We At Correctly Interrupting Our Emotions?

- Should you Go with your Gut?

- Abortion leads to mental health problems?

- Can the Heart Store Memories?

- Does the Duck/Rabbit Illusion Work as a Test of Creativity?

Recent Comments

- February 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- Uncategorized

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Case Study vs. Experimental Research

What's the difference.

Case study and experimental research are both methods used in scientific inquiry to gather data and draw conclusions. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. Case study research involves in-depth analysis of a single individual, group, or event, often using qualitative methods to explore complex phenomena. On the other hand, experimental research involves manipulating variables and measuring their effects on outcomes in a controlled setting to establish cause-and-effect relationships. While case studies provide rich, detailed insights into specific cases, experimental research allows for more generalizable findings and the ability to establish causal relationships between variables. Both methods have their strengths and limitations, and researchers often choose the most appropriate method based on their research questions and objectives.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Case study and experimental research are two common research methods used in various fields such as psychology, sociology, and business. While both methods aim to gather data and draw conclusions, they have distinct attributes that set them apart. In this article, we will compare the attributes of case study and experimental research to understand their strengths and weaknesses.

Case study research involves an in-depth analysis of a single individual, group, or event. Researchers collect detailed information through various sources such as interviews, observations, and documents to gain a comprehensive understanding of the case. On the other hand, experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effects on an outcome. Researchers control the conditions of the study to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Research Design

In case study research, the design is typically exploratory and descriptive. Researchers aim to provide a detailed account of the case under study without manipulating variables. The focus is on understanding the complexities and nuances of the case. In contrast, experimental research follows a more structured and controlled design. Researchers manipulate variables, establish control groups, and randomize participants to ensure internal validity.

Data Collection

Case study research relies on multiple sources of data such as interviews, observations, and documents. Researchers gather qualitative data to provide rich descriptions and insights into the case. The data collection process is often iterative, allowing researchers to delve deeper into the case. Experimental research, on the other hand, focuses on quantitative data collected through controlled experiments. Researchers use standardized procedures to ensure reliability and validity of the data.

Generalizability

One of the key differences between case study and experimental research is the issue of generalizability. Case study research is often criticized for its limited generalizability due to the focus on a single case. The findings may not be applicable to a larger population. In contrast, experimental research aims for generalizability by using random sampling and control groups. The results can be applied to a broader population with confidence.

Validity is another important aspect to consider when comparing case study and experimental research. Case study research often emphasizes internal validity, ensuring that the findings accurately represent the case under study. Researchers use multiple sources of data and triangulation to enhance the validity of the findings. Experimental research, on the other hand, focuses on both internal and external validity. Researchers control for confounding variables and aim to generalize the findings to a larger population.

Ethical Considerations

Both case study and experimental research raise ethical considerations that researchers must address. In case study research, researchers must ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants. They also need to obtain informed consent and minimize any potential harm to the participants. Experimental research involves ethical considerations such as informed consent, debriefing, and protection of participants from harm. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to ensure the well-being of the participants.

Applications

Case study research is often used in fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology to explore complex phenomena in real-world settings. Researchers can gain a deep understanding of individual experiences and behaviors through case studies. Experimental research, on the other hand, is commonly used in natural and social sciences to establish causal relationships between variables. Researchers can test hypotheses and make predictions based on experimental findings.

In conclusion, case study and experimental research are two valuable research methods with distinct attributes. While case study research provides in-depth insights into individual cases, experimental research allows for the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships. Researchers should consider the research design, data collection methods, generalizability, validity, and ethical considerations when choosing between case study and experimental research. Both methods have their strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of method should align with the research objectives and questions.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

- [email protected]

- Connecting and sharing with us

- Entrepreneurship

- Growth of firm

- Sales Management

- Retail Management

- Import – Export

- International Business

- Project Management

- Production Management

- Quality Management

- Logistics Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Human Resource Management

- Organizational Culture

- Information System Management

- Corporate Finance

- Stock Market

- Office Management

- Theory of the Firm

- Management Science

- Microeconomics

- Research Process

- Experimental Research

- Research Philosophy

- Management Research

- Writing a thesis

- Writing a paper

- Literature Review

- Action Research

- Qualitative Content Analysis

- Observation

- Phenomenology

- Statistics and Econometrics

- Questionnaire Survey

- Quantitative Content Analysis

- Meta Analysis

Comparing Case Studies with Other Research Methods in the Social Sciences

When and why would you want to do case studies on some topic? Should you consider doing an experiment instead? A survey? A history? An analysis of archival records, such as modeling economic trends or student performance in schools? 1

These and other choices represent different research methods. Each is a different way of collecting and analyzing empirical evidence, following its own logic. And each method has its own advantages and disadvantages. To get the most out of using the case study method, you need to appreciate these differences.

A common misconception is that the various research methods should be arrayed hierarchically. Many social scientists still deeply believe that case studies are only appropriate for the exploratory phase of an investigation, that surveys and histories are appropriate for the descriptive phase, and that experiments are the only way of doing explanatory or causal inquiries. This hierarchical view reinforces the idea that case studies are only a preliminary research method and cannot be used to describe or test propositions.

This hierarchical view, however, may be questioned. Experiments with an exploratory motive have certainly always existed. In addition, the development of causal explanations has long been a serious concern of historians, reflected by the subfield known as historiography. Likewise, case studies are far from being only an exploratory strategy. Some of the best and most famous case studies have been explanatory case studies (e.g., see BOX 1 for a vignette on Allison and Zelikow’s Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1999). Similarly, famous descriptive case studies are found in major disciplines such as sociology and political science (e.g., see BOX 2 for two vignettes). Additional examples of explanatory case studies are presented in their entirety in a companion book cited throughout this text (Yin, 2003, chaps. 4-7). Examples of descriptive case studies are similarly found there (Yin, 2003, chaps. 2 and 3).

Distinguishing among the various research methods and their advantages and disadvantages may require going beyond the hierarchical stereotype. The more appropriate view may be an inclusive and pluralistic one: Every research method can be used for all three purposes—exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory. There may be exploratory case studies, descriptive case studies, or explanatory case studies. Similarly, there may be exploratory experiments, descriptive experiments, and explanatory experiments. What distinguishes the different methods is not a hierarchy but three important conditions discussed below. As an important caution, however, the clarification does not imply that the boundaries between the methods—or the occasions when each is to be used—are always sharp. Even though each method has its distinctive characteristics, there are large overlaps among them. The goal is to avoid gross misfits—that is, when you are planning to use one type of method but another is really more advantageous.

1. When to Use Each Method

The three conditions consist of (a) the type of research question posed, (b) the extent of control an investigator has over actual behavioral events, and (c) the degree of focus on contemporary as opposed to historical events. Figure 1.1 displays these three conditions and shows how each is related to the five major research methods being discussed: experiments, surveys, archival analyses, histories, and case studies. The importance of each condition, in distinguishing among the five methods, is as follows.

Types of research questions (Figure 1.1, column 1). The first condition covers your research question(s) (Hedrick, Bickman, & Rog, 1993). A basic categorization scheme for the types of questions is the familiar series: “who,” “what,” “where,” “how,” and “why” questions.

If research questions focus mainly on “what” questions, either of two possibilities arises. First, some types of “what” questions are exploratory, such as “What can be learned from a study of a startup business?” This type of question is a justifiable rationale for conducting an exploratory study, the goal being to develop pertinent hypotheses and propositions for further inquiry. However, as an exploratory study, any of the five research methods can be used—for example, an exploratory survey (testing, for instance, the ability to survey startups in the first place), an exploratory experiment (testing, for instance, the potential benefits of different kinds of incentives), or an exploratory case study (testing, for instance, the importance of differentiating “first-time” startups from startups by entrepreneurs who had previously started other firms).

The second type of “what” question is actually a form of a “how many” or “how much” line of inquiry—for example, “What have been the ways that communities have assimilated new immigrants?” Identifying such ways is more likely to favor survey or archival methods than others. For example, a survey can be readily designed to enumerate the “what,” whereas a case study would not be an advantageous method in this situation.

Similarly, like this second type of “what” question, “who” and “where” questions (or their derivatives—“how many” and “how much”) are likely to favor survey methods or the analysis of archival data, as in economic studies. These methods are advantageous when the research goal is to describe the incidence or prevalence of a phenomenon or when it is to be predictive about certain outcomes. The investigation of prevalent political attitudes (in which a survey or a poll might be the favored method) or of the spread of a disease like AIDS (in which an epidemiologic analysis of health statistics might be the favored method) would be typical examples.

In contrast, “how” and “why” questions are more explanatory and likely to lead to the use of case studies, histories, and experiments as the preferred research methods. This is because such questions deal with operational links needing to be traced over time, rather than mere frequencies or incidence. Thus, if you wanted to know how a community successfully overcame the negative impact of the closing of its largest employer—a military base (see Bradshaw, 1999, also presented in BOX 26, Chapter 5, p. 138)—you would be less likely to rely on a survey or an examination of archival records and might be better off doing a history or a case study. Similarly, if you wanted to know how research investigators may possibly (but unknowingly) bias their research, you could design and conduct a series of experiments (see Rosenthal, 1966).

Let us take two more examples. If you were studying “who” had suffered as a result of terrorist acts and “how much” damage had been done, you might survey residents, examine government records (an archival analysis), or conduct a “windshield survey” of the affected area. In contrast, if you wanted to know “why” the act had occurred, you would have to draw upon a wider array of documentary information, in addition to conducting interviews; if you focused on the “why” question in more than one terrorist act, you would probably be doing a multiple-case study.

Similarly, if you wanted to know “what” the outcomes of a new governmental program had been, you could answer this question by doing a survey or by examining economic data, depending upon the type of program involved. Questions—such as “How many clients did the program serve?” “What kinds of benefits were received?” “How often were different benefits produced?”— all could be answered without doing a case study. But if you needed to know “how” or “why” the program had worked (or not), you would lean toward either a case study or a field experiment.

To summarize, the first and most important condition for differentiating among the various research methods is to classify the type of research question being asked. In general, “what” questions may either be exploratory (in which case, any of the methods could be used) or about prevalence (in which surveys or the analysis of archival records would be favored). “How” and “why” questions are likely to favor the use of case studies, experiments, or histories.

EXERCISE 1.1 Defining a Case Study Question

Develop a “how” or “why” question that would be the rationale for a case study that you might conduct. Instead of doing a case study, now imagine that you only could do a history, a survey, or an experiment (but not a case study) in order to answer this question. What would be the distinctive advantage of doing a case study, compared to these other methods, in order to answer this question?

Defining the research questions is probably the most important step to be taken in a research study, so you should be patient and allow sufficient time for this task. The key is to understand that your research questions have both substance—for example, What is my study about?—and form—for example, am I asking a “who,” “what,” “where,” “why,” or “how” question? Others have focused on some of the substantively important issues (see J. P. Campbell, Daft, & Hulin, 1982); the point of the preceding discussion is that the form of the question can provide an important clue regarding the appropriate research method to be used. Remember, too, the large areas of overlap among the methods, so that, for some questions, a choice among methods might actually exist. Be aware, finally, that you (or your academic department) may be predisposed to favor a particular method regardless of the study question. If so, be sure to create the form of the study question best matching the method you were predisposed to favor in the first place.

EXERCISE 1.2 Identifying the Research Questions Covered When Other Research Methods Are Used

Locate a research study based solely on the use of survey, historical, or experimental (but not case study) methods. Identify the research question(s) addressed by the study. Does the type of question differ from those that might have appeared as part of a case study on the same topic, and if so, how?

Extent of control over behavioral events (Figure 1.1, column 2) and degree of focus on contemporary as opposed to historical events (Figure 1.1, column 3). Assuming that “how” and “why” questions are to be the focus of study, a further distinction among history, case study, and experiment is the extent of the investigator’s control over and access to actual behavioral events. Histories are the preferred method when there is virtually no access or control. The distinctive contribution of the historical method is in dealing with the “dead” past— that is, when no relevant persons are alive to report, even retrospectively, what occurred and when an investigator must rely on primary documents, secondary documents, and cultural and physical artifacts as the main sources of evidence. Histories can, of course, be done about contemporary events; in this situation, the method begins to overlap with that of the case study.

The case study is preferred in examining contemporary events, but when the relevant behaviors cannot be manipulated. The case study relies on many of the same techniques as a history, but it adds two sources of evidence not usually included in the historian’s repertoire: direct observation of the events being studied and interviews of the persons involved in the events. Again, although case studies and histories can overlap, the case study’s unique strength is its ability to deal with a full variety of evidence—documents, artifacts, interviews, and observations—beyond what might be available in a conventional historical study. Moreover, in some situations, such as participant-observation (see Chapter 4), informal manipulation can occur.

Finally, experiments are done when an investigator can manipulate behavior directly, precisely, and systematically. This can occur in a laboratory setting, in which an experiment may focus on one or two isolated variables (and presumes that the laboratory environment can “control” for all the remaining variables beyond the scope of interest), or it can be done in a field setting, where the term field or social experiment has emerged to cover research where investigators “treat” whole groups of people in different ways, such as providing them with different kinds of vouchers to purchase services (Boruch & Foley, 2000). Again, the methods overlap. The full range of experimental science also includes those situations in which the experimenter cannot manipulate behavior but in which the logic of experimental design still may be applied. These situations have been commonly regarded as “quasi-experimental” situations (e.g., D. T. Campbell & Stanley, 1966; Cook & Campbell, 1979) or “observational” studies (e.g., P. R. Rosenbaum, 2002). The quasi-experimental approach even can be used in a historical setting, where, for instance, an investigator may be interested in studying race riots or lynchings (see Spilerman, 1971) and use a quasi-experimental design because no control over the behavioral event was possible. In this case, the experimental method begins to overlap with histories.

In the field of evaluation research, Boruch and Foley (2000) have made a compelling argument for the practicality of one type of field experiment—randomized field trials. The authors maintain that the field trials design, emulating the design of laboratory experiments, can be and has been used even when evaluating complex community initiatives. However, you should be cautioned about the possible limitations of this design.

In particular, the design may work well when, within a community, individual consumers or users of services are the unit of analysis. Such a situation would exist if a community intervention consisted, say, of a health promotion campaign and the outcome of interest was the incidence of certain illnesses among the community’s residents. The random assignment might designate a few communities to have the campaign, compared to a few that did not, and the outcomes would compare the condition of the residents in both sets of communities.

In many community studies, however, the outcomes of interest and therefore the appropriate unit of analysis are at the community or collective level and not at the individual level. For instance, efforts to upgrade neighborhoods may be concerned with improving a neighborhood’s economic base (e.g., the number of jobs per residential population). Now, although the candidate communities still can be randomly assigned, the degrees of freedom in any later statistical analysis are limited by the number of communities rather than the number of residents. Most field experiments will not be able to support the participation of a sufficiently large number of communities to overcome the severity of the subsequent statistical constraints.

The limitations when communities or collective entities are the unit of analysis are extremely important because many public policy objectives focus on the collective rather than individual level. For instance, the thrust of federal education policy in the early 2000s focused on school performance. Schools were held accountable for year-to-year performance even though the composition of the students enrolled at the schools changed each year. Creating and implementing a field trial based on a large number of schools, as opposed to a large number of students, would present an imposing challenge and the need for extensive research resources. In fact, Boruch (2007) found that a good number of the randomized field trials inadvertently used the incorrect unit of analysis (individuals rather than collectives), thereby making the findings from the trials less usable.

Field experiments with a large number of collective entities (e.g., neighborhoods, schools, or organizations) also raise a number of practical challenges:

- any randomly selected control sites may adopt important components of the intervention of interest before the end of the field experiment and no longer qualify as “no-treatment” sites;

- the funded intervention may call for the experimental communities to reorganize their entire manner of providing certain services—that is, a “systems” change— thereby creating site-to-site variability in the unit of assignment (the experimental design assumes that the unit of assignment is the same at every site, both intervention and control);

- the same systems change aspect of the intervention also may mean that the organizations or entities administering the intervention may not necessarily remain stable over the course of time (the design requires such stability until the random field trials have been completed); and

- the experimental or control sites may be unable to continue using the same instruments and measures (the design, which will ultimately “group” the data to compare intervention sites as a group with comparison sites as a second group, requires common instruments and measures across sites).

The existence of any of these conditions will likely lead to the need to find alternatives to randomized field trials.

Summary. You should be able to identify some situations in which all research methods might be relevant (such as exploratory research) and other situations in which two methods might be considered equally attractive. You also can use multiple methods in any given study (for example, a survey within a case study or a case study within a survey). To this extent, the various methods are not mutually exclusive. But you should also be able to identify some situations in which a specific method has a distinct advantage. For the case study, this is when

- a contemporary set of events,

- over which the investigator has little or no control.

To determine the questions that are most significant for a topic, as well as to gain some precision in formulating these questions requires much preparation. One way is to review the literature on the topic (Cooper, 1984). Note that such a literature review is therefore a means to an end, and not—as many people have been taught to think—an end in itself. Novices may think that the purpose of a literature review is to determine the answers about what is known on a topic; in contrast, experienced investigators review previous research to develop sharper and more insightful questions about the topic.

2. Traditional Prejudices against the Case Study Method

Although the case study is a distinctive form of empirical inquiry, many research investigators nevertheless disdain the strategy. In other words, as a research endeavor, case studies have been viewed as a less desirable form of inquiry than either experiments or surveys. Why is this?

Perhaps the greatest concern has been over the lack of rigor of case study research. Too many times, the case study investigator has been sloppy, has not followed systematic procedures, or has allowed equivocal evidence or biased views to influence the direction of the findings and conclusions. Such lack of rigor is less likely to be present when using the other methods—possibly because of the existence of numerous methodological texts providing investigators with specific procedures to be followed. In contrast, only a small (though increasing) number of texts besides the present one cover the case study method in similar fashion.

The possibility also exists that people have confused case study teaching with case study research. In teaching, case study materials may be deliberately altered to demonstrate a particular point more effectively (e.g., Garvin, 2003). In research, any such step would be strictly forbidden. Every case study investigator must work hard to report all evidence fairly, and this book will help her or him to do so. What is often forgotten is that bias also can enter into the conduct of experiments (see Rosenthal, 1966) and the use of other research methods, such as designing questionnaires for surveys (Sudman & Bradbum, 1982) or conducting historical research (Gottschalk, 1968). The problems are not different, but in case study research, they may have been more frequently encountered and less frequently overcome.

EXERCISE 1.3 Examining Case Studies Used for Teaching Purposes

Obtain a copy of a case study designed for teaching purposes (e.g., a case in a textbook used in a business school course). Identify the specific ways in which this type of “teaching” case is different from research case studies.

Does the teaching case cite primary documents, contain evidence, or display data? Does the teaching case have a conclusion? What appears to be the main objective of the teaching case?

A second common concern about case studies is that they provide little basis for scientific generalization. “How can you generalize from a single case?” is a frequently heard question. The answer is not simple (Kennedy, 1976). However, consider for the moment that the same question had been asked about an experiment: “How can you generalize from a single experiment?” In fact, scientific facts are rarely based on single experiments; they are usually based on a multiple set of experiments that have replicated the same phenomenon under different conditions. The same approach can be used with multiple-case studies but requires a different concept of the appropriate research designs, discussed in detail in Chapter 2. The short answer is that case studies, like experiments, are generalizable to theoretical propositions and not to populations or universes. In this sense, the case study, like the experiment, does not represent a “sample,” and in doing a case study, your goal will be to expand and generalize theories (analytic generalization) and not to enumerate frequencies (statistical generalization). Or, as three notable social scientists describe in their single case study done years ago, the goal is to do a “generalizing” and not a “particularizing” analysis (Lipset, Trow, & Coleman, 1956, pp. 419-420). 2

A third frequent complaint about case studies is that they take too long, and they result in massive, unreadable documents. This complaint may be appropriate, given the way case studies have been done in the past (e.g., Feagin, Orum, & Sjoberg, 1991), but this is not necessarily the way case studies—yours included—must be done in the future. Chapter 6 discusses alternative ways of writing the case study—including ones in which the traditional, lengthy narrative can be avoided altogether. Nor need case studies take a long time. This incorrectly confuses the case study method with a specific method of data collection, such as ethnography (e.g., Fetterman, 1989) or participant-observation (e.g., Jorgensen, 1989). Ethnographies usually require long periods of time in the “field” and emphasize detailed, observational evidence. Participant-observation may not require the same length of time but still assumes a hefty investment of field efforts. In contrast, case studies are a form of inquiry that does not depend solely on ethnographic or participant-observer data. You could even do a valid and high-quality case study without leaving the telephone or Internet, depending upon the topic being studied.

A fourth possible objection to case studies has seemingly emerged with the renewed emphasis, especially in education and related research, on randomized field trials or “true experiments.” Such studies aim to establish causal relationships—that is, whether a particular “treatment” has been efficacious in producing a particular “effect” (e.g., Jadad, 1998). In the eyes of many, the emphasis has led to a downgrading of case study research because case studies (and other types of nonexperimental methods) cannot directly address this issue.

Overlooked has been the possibility that case studies can offer important evidence to complement experiments. Some noted methodologists suggest, for instance, that experiments, though establishing the efficacy of a treatment (or intervention), are limited in their ability to explain “how” or “why” the treatment necessaiily worked, whereas case studies could investigate such issues (e.g., Shavelson & Townes, 2002, pp. 99-106). 3 Case studies may therefore be valued “as adjuncts to experiments rather than as alternatives to them” (Cook & Payne, 2002). In clinical psychology, a “large series of single case studies,” confirming predicted behavioral changes after the initiation of treatment, even may provide additional evidence of efficaciousness (e.g., Veerman & van Yperen, 2007).

Despite the fact that these four common concerns can be allayed, as above, one major lesson is that good case studies are still difficult to do. The problem is that we have little way of screening for an investigator’s ability to do good case studies. People know when they cannot play music; they also know when they cannot do mathematics beyond a certain level, and they can be tested for other skills, such as the bar examination in law. Somehow, the skills for doing good case studies have not yet been formally defined. As a result, “most people feel that they can prepare a case study, and nearly all of us believe we can understand one. Since neither view is well founded, the case study receives a good deal of approbation it does not deserve” (Hoaglin, Light, McPeek, Mosteller, & Stoto, 1982, p. 134). This quotation is from a book by five prominent statisticians. Surprisingly, from another field, even they recognize the challenge of doing good case studies.

Source: Yin K Robert (2008), Case Study Research Designs and Methods , SAGE Publications, Inc; 4th edition.

13 Aug 2021

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Username or email address *

Password *

Log in Remember me

Lost your password?

10 Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A case study in academic research is a detailed and in-depth examination of a specific instance or event, generally conducted through a qualitative approach to data.

The most common case study definition that I come across is is Robert K. Yin’s (2003, p. 13) quote provided below:

“An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

Researchers conduct case studies for a number of reasons, such as to explore complex phenomena within their real-life context, to look at a particularly interesting instance of a situation, or to dig deeper into something of interest identified in a wider-scale project.

While case studies render extremely interesting data, they have many limitations and are not suitable for all studies. One key limitation is that a case study’s findings are not usually generalizable to broader populations because one instance cannot be used to infer trends across populations.

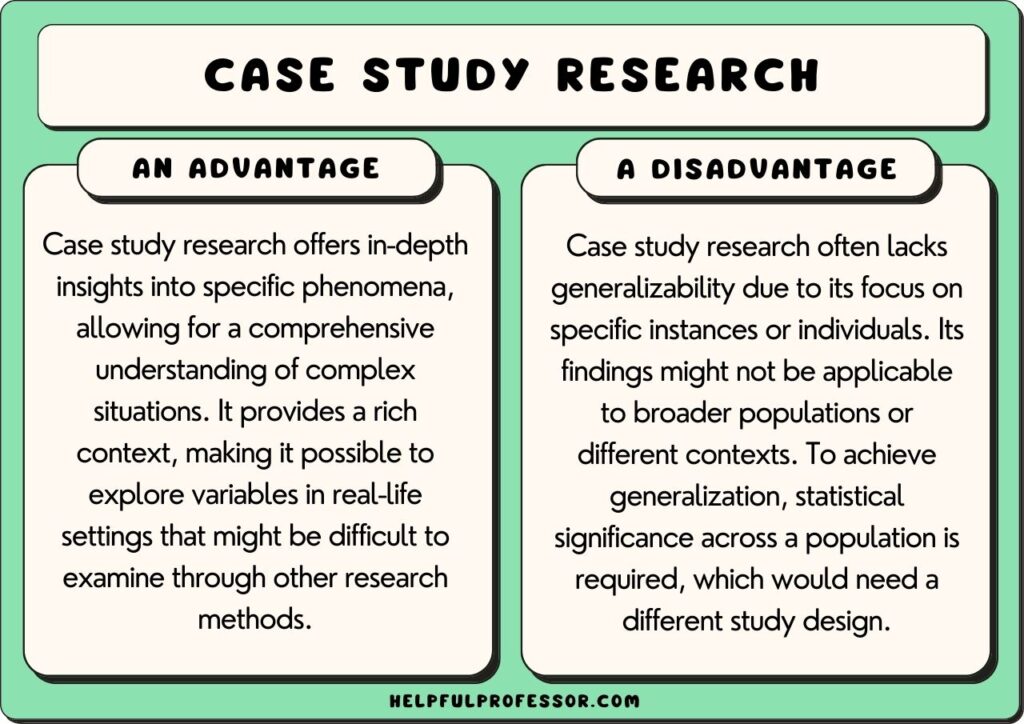

Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

1. in-depth analysis of complex phenomena.

Case study design allows researchers to delve deeply into intricate issues and situations.

By focusing on a specific instance or event, researchers can uncover nuanced details and layers of understanding that might be missed with other research methods, especially large-scale survey studies.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue,

“It allows that particular event to be studies in detail so that its unique qualities may be identified.”

This depth of analysis can provide rich insights into the underlying factors and dynamics of the studied phenomenon.

2. Holistic Understanding

Building on the above point, case studies can help us to understand a topic holistically and from multiple angles.

This means the researcher isn’t restricted to just examining a topic by using a pre-determined set of questions, as with questionnaires. Instead, researchers can use qualitative methods to delve into the many different angles, perspectives, and contextual factors related to the case study.

We can turn to Lee and Saunders (2017) again, who notes that case study researchers “develop a deep, holistic understanding of a particular phenomenon” with the intent of deeply understanding the phenomenon.

3. Examination of rare and Unusual Phenomena

We need to use case study methods when we stumble upon “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017) phenomena that would tend to be seen as mere outliers in population studies.

Take, for example, a child genius. A population study of all children of that child’s age would merely see this child as an outlier in the dataset, and this child may even be removed in order to predict overall trends.

So, to truly come to an understanding of this child and get insights into the environmental conditions that led to this child’s remarkable cognitive development, we need to do an in-depth study of this child specifically – so, we’d use a case study.

4. Helps Reveal the Experiences of Marginalzied Groups

Just as rare and unsual cases can be overlooked in population studies, so too can the experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of marginalized groups.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue, “case studies are also extremely useful in helping the expression of the voices of people whose interests are often ignored.”

Take, for example, the experiences of minority populations as they navigate healthcare systems. This was for many years a “hidden” phenomenon, not examined by researchers. It took case study designs to truly reveal this phenomenon, which helped to raise practitioners’ awareness of the importance of cultural sensitivity in medicine.

5. Ideal in Situations where Researchers cannot Control the Variables

Experimental designs – where a study takes place in a lab or controlled environment – are excellent for determining cause and effect . But not all studies can take place in controlled environments (Tetnowski, 2015).

When we’re out in the field doing observational studies or similar fieldwork, we don’t have the freedom to isolate dependent and independent variables. We need to use alternate methods.

Case studies are ideal in such situations.

A case study design will allow researchers to deeply immerse themselves in a setting (potentially combining it with methods such as ethnography or researcher observation) in order to see how phenomena take place in real-life settings.

6. Supports the generation of new theories or hypotheses

While large-scale quantitative studies such as cross-sectional designs and population surveys are excellent at testing theories and hypotheses on a large scale, they need a hypothesis to start off with!

This is where case studies – in the form of grounded research – come in. Often, a case study doesn’t start with a hypothesis. Instead, it ends with a hypothesis based upon the findings within a singular setting.

The deep analysis allows for hypotheses to emerge, which can then be taken to larger-scale studies in order to conduct further, more generalizable, testing of the hypothesis or theory.

7. Reveals the Unexpected

When a largescale quantitative research project has a clear hypothesis that it will test, it often becomes very rigid and has tunnel-vision on just exploring the hypothesis.

Of course, a structured scientific examination of the effects of specific interventions targeted at specific variables is extermely valuable.

But narrowly-focused studies often fail to shine a spotlight on unexpected and emergent data. Here, case studies come in very useful. Oftentimes, researchers set their eyes on a phenomenon and, when examining it closely with case studies, identify data and come to conclusions that are unprecedented, unforeseen, and outright surprising.

As Lars Meier (2009, p. 975) marvels, “where else can we become a part of foreign social worlds and have the chance to become aware of the unexpected?”

Disadvantages

1. not usually generalizable.

Case studies are not generalizable because they tend not to look at a broad enough corpus of data to be able to infer that there is a trend across a population.

As Yang (2022) argues, “by definition, case studies can make no claims to be typical.”

Case studies focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. They explore the context, nuances, and situational factors that have come to bear on the case study. This is really useful for bringing to light important, new, and surprising information, as I’ve already covered.

But , it’s not often useful for generating data that has validity beyond the specific case study being examined.

2. Subjectivity in interpretation

Case studies usually (but not always) use qualitative data which helps to get deep into a topic and explain it in human terms, finding insights unattainable by quantitative data.

But qualitative data in case studies relies heavily on researcher interpretation. While researchers can be trained and work hard to focus on minimizing subjectivity (through methods like triangulation), it often emerges – some might argue it’s innevitable in qualitative studies.

So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies.

3. Difficulty in replicating results

Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.

So, when returning to a setting to re-do or attempt to replicate a study, we often find that the variables have changed to such an extent that replication is difficult. Furthermore, new researchers (with new subjective eyes) may catch things that the other readers overlooked.

Replication is even harder when researchers attempt to replicate a case study design in a new setting or with different participants.

Comprehension Quiz for Students

Question 1: What benefit do case studies offer when exploring the experiences of marginalized groups?

a) They provide generalizable data. b) They help express the voices of often-ignored individuals. c) They control all variables for the study. d) They always start with a clear hypothesis.

Question 2: Why might case studies be considered ideal for situations where researchers cannot control all variables?

a) They provide a structured scientific examination. b) They allow for generalizability across populations. c) They focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. d) They allow for deep immersion in real-life settings.

Question 3: What is a primary disadvantage of case studies in terms of data applicability?

a) They always focus on the unexpected. b) They are not usually generalizable. c) They support the generation of new theories. d) They provide a holistic understanding.

Question 4: Why might case studies be considered more prone to subjectivity?

a) They always use quantitative data. b) They heavily rely on researcher interpretation, especially with qualitative data. c) They are always replicable. d) They look at a broad corpus of data.

Question 5: In what situations are experimental designs, such as those conducted in labs, most valuable?

a) When there’s a need to study rare and unusual phenomena. b) When a holistic understanding is required. c) When determining cause-and-effect relationships. d) When the study focuses on marginalized groups.

Question 6: Why is replication challenging in case study research?

a) Because they always use qualitative data. b) Because they tend to focus on a broad corpus of data. c) Due to the changing variables in complex real-world settings. d) Because they always start with a hypothesis.

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Meir, L. (2009). Feasting on the Benefits of Case Study Research. In Mills, A. J., Wiebe, E., & Durepos, G. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vol. 2). London: SAGE Publications.

Tetnowski, J. (2015). Qualitative case study research design. Perspectives on fluency and fluency disorders , 25 (1), 39-45. ( Source )

Yang, S. L. (2022). The War on Corruption in China: Local Reform and Innovation . Taylor & Francis.

Yin, R. (2003). Case Study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Free Social Skills Worksheets

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Case studies and experiments are both research methods used in various fields to gather data and draw conclusions. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. A case study involves in-depth analysis of a particular individual, group, or situation, aiming to provide a detailed understanding of a specific phenomenon.

Oct 30, 2024 · Difference Between Case Study and Experiment. Now that we know the premise of both, let's leap to the differences between a case study and an experiment: Purpose. A case study attempts to gain a rich understanding of one specific case. This method is very useful in answering very open-ended questions such as "why" or "how" something happened.

May 11, 2023 · Case studies and experiments are two distinct research methods used across various disciplines, providing researchers with the ability to study and analyze a subject through different approaches. This variety in research methods allows the researcher to gather both qualitative and quantitative data, cross-check the data, and assign greater ...

Apr 16, 2024 · A case study and experiment are the two prominent approaches often used at the forefront of scholarly inquiry. While case studies study the complexities of real-life situations, aiming for depth and contextual understanding, experiments seek to uncover causal relationships through controlled manipulation and observation.

Case studies differ from other types of research in several ways: They rely heavily on qualitative data: As mentioned above, one key distinction between a case study and other forms of research is that it relies heavily on qualitative data — such as interviews — rather than quantitative data like surveys or experiments. Qualitative data ...

Feb 8, 2020 · Case studies are conducted in real life (field experiments) scenarios and generally are designed to solve or formulate an answer or solution to some type of issue or problem. Contrary to the survey, case studies generally focus on a limited number of situations but the situations are more detailed, producing the goal of more depth than breadth ...

Nov 16, 2011 · In my opinion both methods have great importance to the field of psychology. Experiments provide a great deal of control (Lab studies) and allow the research to be conducted in a much more natural environment (Field studies). Whereas case studies provide us with much more detailed and rich research about individuals, towards human behaviour.

Case study and experimental research are both methods used in scientific inquiry to gather data and draw conclusions. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. Case study research involves in-depth analysis of a single individual, group, or event, often using qualitative methods to explore complex phenomena.

Aug 13, 2021 · 2. Traditional Prejudices against the Case Study Method. Although the case study is a distinctive form of empirical inquiry, many research investigators nevertheless disdain the strategy. In other words, as a research endeavor, case studies have been viewed as a less desirable form of inquiry than either experiments or surveys. Why is this?

Oct 17, 2023 · So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies. 3. Difficulty in replicating results. Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.