This document originally came from the Journal of Mammalogy courtesy of Dr. Ronald Barry, a former editor of the journal.

How to Format a Scientific Paper

#scribendiinc

Written by Joanna Kimmerly-Smith

You've done the research. You've carefully recorded your lab results and compiled a list of relevant sources. You've even written a draft of your scientific, technical, or medical paper, hoping to get published in a reputable journal. But how do you format your paper to ensure that every detail is correct? If you're a scientific researcher or co-author looking to get your research published, read on to find out how to format your paper.

While it's true that you'll eventually need to tailor your research for your target journal, which will provide specific author guidelines for formatting the paper (see, for example, author guidelines for publications by Elsevier , PLOS ONE , and mBio ), there are some formatting rules that are useful to know for your initial draft. This article will explore some of the formatting rules that apply to all scientific writing, helping you to follow the correct order of sections ( IMRaD ), understand the requirements of each section, find resources for standard terminology and units of measurement, and prepare your scientific paper for publication.

Format Overview

The four main elements of a scientific paper can be represented by the acronym IMRaD: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. Other sections, along with a suggested length,* are listed in the table below.

* Length guidelines are taken from https://www.elsevier.com/connect/11-steps-to-structuring-a-science-paper-editors-will-take-seriously#step6 .

Now, let's go through the main sections you might have to prepare to format your paper.

On the first page of the paper, you must present the title of the paper along with the authors' names, institutional affiliations, and contact information. The corresponding author(s) (i.e., the one[s] who will be in contact with the reviewers) must be specified, usually with a footnote or an asterisk (*), and their full contact details (e.g., email address and phone number) must be provided. For example:

Dr. Clara A. Bell 1, * and Dr. Scott C. Smith 2

1 University of Areopagitica, Department of Biology, Sometown, Somecountry

2 Leviathan University, Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, Sometown, Somecountry

FORMATTING TIPS:

- If you are unsure of how to classify author roles (i.e., who did what), guidelines are available online. For example, American Geophysical Union (AGU) journals now recommend using Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT), an online taxonomy for author contributions.

In this summary of your research, you must state your subject (i.e., what you did) and encapsulate the main findings and conclusions of your paper.

- Do not add citations in an abstract (the reader might not be able to access your reference list).

- Avoid using acronyms and abbreviations in the abstract, as the reader may not be familiar with them. Use full terms instead.

Below the abstract, include a list of key terms to help other researchers locate your study. Note that "keywords" is one word (with no space) and is followed by a colon:

Keywords : paper format, scientific writing.

- Check whether "Keywords" should be italicized and whether each term should be capitalized.

- Check the use of punctuation (e.g., commas versus semicolons, the use of the period at the end).

- Some journals (e.g., IEEE ) provide a taxonomy of keywords. This aids in the classification of your research.

Introduction

This is the reader's first impression of your paper, so it should be clear and concise. Include relevant background information on your topic, using in-text citations as necessary. Report new developments in the field, and state how your research fills gaps in the existing research. Focus on the specific problem you are addressing, along with its possible solutions, and outline the limitations of your study. You can also include a research question, hypothesis, and/or objectives at the end of this section.

- Organize your information from broad to narrow (general to particular). However, don't start too broad; keep the information relevant.

- You can use in-text citations in this section to situate your research within the body of literature.

This is the part of your paper that explains how the research was done. You should relate your research procedures in a clear, logical order (i.e., the order in which you conducted the research) so that other researchers can reproduce your results. Simply refer to the established methods you used, but describe any procedures that are original to your study in more detail.

- Identify the specific instruments you used in your research by including the manufacturer’s name and location in parentheses.

- Stay consistent with the order in which information is presented (e.g., quantity, temperature, stirring speed, refrigeration period).

Now that you've explained how you gathered your research, you've got to report what you actually found. In this section, outline the main findings of your research. You need not include too many details, particularly if you are using tables and figures. While writing this section, be consistent and use the smallest number of words necessary to convey your statistics.

- Use appendices or supplementary materials if you have too much data.

- Use headings to help the reader follow along, particularly if your data are repetitive (but check whether your style guide allows you to use them).

In this section, you interpret your findings for the reader in relation to previous research and the literature as a whole. Present your general conclusions, including an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the research and the implications of your findings. Resolve the hypothesis and/or research question you identified in the introduction.

- Use in-text citations to support your discussion.

- Do not repeat the information you presented in the results or the introduction unless it is necessary for a discussion of the overall implications of the research.

This section is sometimes included in the last paragraph of the discussion. Explain how your research fits within your field of study, and identify areas for future research.

- Keep this section short.

Acknowledgments

Write a brief paragraph giving credit to any institution responsible for funding the study (e.g., through a fellowship or grant) and any individual(s) who contributed to the manuscript (e.g., technical advisors or editors).

- Check whether your journal uses standard identifiers for funding agencies (e.g., Elsevier's Funder Registry ).

Conflicts of Interest/Originality Statement

Some journals require a statement attesting that your research is original and that you have no conflicts of interest (i.e., ulterior motives or ways in which you could benefit from the publication of your research). This section only needs to be a sentence or two long.

Here you list citation information for each source you used (i.e., author names, date of publication, title of paper/chapter, title of journal/book, and publisher name and location). The list of references can be in alphabetical order (author–date style of citation) or in the order in which the sources are presented in the paper (numbered citations). Follow your style guide; if no guidelines are provided, choose a citation format and be consistent .

- While doing your final proofread, ensure that the reference list entries are consistent with the in-text citations (i.e., no missing or conflicting information).

- Many citation styles use a hanging indent and may be alphabetized. Use the styles in Microsoft Word to aid you in citation format.

- Use EndNote , Mendeley , Zotero , RefWorks , or another similar reference manager to create, store, and utilize bibliographic information.

Appendix/Supplementary Information

In this optional section, you can present nonessential information that further clarifies a point without burdening the body of the paper. That is, if you have too much data to fit in a (relatively) short research paper, move anything that's not essential to this section.

- Note that this section is uncommon in published papers. Before submission, check whether your journal allows for supplementary data, and don't put any essential information in this section.

Beyond IMRaD: Formatting the Details

Aside from the overall format of your paper, there are still other details to watch out for. The sections below cover how to present your terminology, equations, tables and figures, measurements, and statistics consistently based on the conventions of scientific writing.

Terminology

Stay consistent with the terms you use. Generally, short forms can be used once the full term has been introduced:

- full terms versus acronyms (e.g., deoxyribonucleic acid versus DNA);

- English names versus Greek letters (e.g., alpha versus α); and

- species names versus short forms (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus versus S. aureus ).

One way to ensure consistency is to use standard scientific terminology. You can refer to the following resources, but if you're not sure which guidelines are preferred, check with your target journal.

- For gene classification, use GeneCards , The Mouse Genome Informatics Database , and/or genenames.org .

- For chemical nomenclature, refer to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) Compendium of Chemical Terminology (the Gold Book ) and the IUPAC–IUB Combined Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature .

- For marine species names, use the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) or the European Register of Marine Species (ERMS) .

Italics must be used correctly for scientific terminology. Here are a couple of formatting tips:

- Species names, which are usually in Greek or Latin, are italicized (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ).

- Genes are italicized, but proteins aren't.

Whether in mathematical, scientific, or technical papers, equations follow a conventional format. Here are some tips for formatting your calculations:

- Number each equation you present in the text, inserting the number in parentheses.

X + Y = 1 (1)

- Check whether your target journal requires you to capitalize the word "Equation" or use parentheses for the equation number when you refer to equations within the text.

In Equation 1, X represents . . .

In equation (1), X represents . . .

(Note also that you should use italics for variables.)

- Try using MathType or Equation Editor in Microsoft Word to type your equations, but use Unicode characters when typing single variables or mathematical operators (e.g., x, ≥, or ±) in running text. This makes it easier to edit your text and format your equations before publication.

- In line with the above tip, remember to save your math equations as editable text and not as images in case changes need to be made before publication.

Tables and Figures

Do you have any tables, graphs, or images in your research? If so, you should become familiar with the rules for referring to tables and figures in your scientific paper. Some examples are presented below.

- Capitalize the titles of specific tables and figures when you refer to them in the text (e.g., "see Table 3"; "in Figure 4").

- In tables, stay consistent with the use of title case (i.e., Capitalizing Each Word) and sentence case (i.e., Capitalizing the first word).

- In figure captions, stay consistent with the use of punctuation, italics, and capitalization. For example:

Figure 1. Classification of author roles.

Figure 2: taxonomy of paper keywords

Measurements

Although every journal has slightly different formatting guidelines, most agree that the gold standard for units of measurement is the International System of Units (SI) . Wherever possible, use the SI. Here are some other tips for formatting units of measurement:

- Add spaces before units of measurement. For example, 2.5 mL not 2.5mL.

- Be consistent with your units of measure (especially date and time). For example, 3 hours or 3 h.

When presenting statistical information, you must provide enough specific information to accurately describe the relationships among your data. Nothing is more frustrating to a reviewer than vague sentences about a variable being significant without any supporting details. The author guidelines for the journal Nature recommend that the following be included for statistical testing: the name of each statistical analysis, along with its n value; an explanation of why the test was used and what is being compared; and the specific alpha levels and P values for each test.

Angel Borja, writing for Elsevier publications, described the statistical rules for article formatting as follows:

- Indicate the statistical tests used with all relevant parameters.

- Use mean and standard deviation to report normally distributed data.

- Use median and interpercentile range to report skewed data.

- For numbers, use two significant digits unless more precision is necessary.

- Never use percentages for very small samples.

Remember, you must be prepared to justify your findings and conclusions, and one of the best ways to do this is through factual accuracy and the acknowledgment of opposing interpretations, data, and/or points of view.

Even though you may not look forward to the process of formatting your research paper, it's important to present your findings clearly, consistently, and professionally. With the right paper format, your chances of publication increase, and your research will be more likely to make an impact in your field. Don't underestimate the details. They are the backbone of scientific writing and research.

One last tip: Before you submit your research, consider using our academic editing service for expert help with paper formatting, editing, and proofreading. We can tailor your paper to specific journal guidelines at your request.

Image source: 85Fifteen/ Unsplash.com

Let Us Format Your Paper to Your Target Journal’s Guidelines

Hire an expert academic editor , or get a free sample, about the author.

Joanna's passion for English literature (proven by her M.A. thesis on Jane Austen) is matched by her passion to help others with their writing (shown by her role as an in-house editor with Scribendi). She enjoys lively discussions about plot, character, and nerdy TV shows with her husband, and she loves singing almost as much as she loves reading. Isn't music another language after all?

Have You Read?

"Abstract vs. Introduction—What's the Difference?"

Related Posts

APA Style and APA Formatting

How to Research a Term Paper

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and Templates

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and Templates

Table of Contents

Research Paper Formats

The format of a research paper is essential for maintaining consistency, clarity, and readability, enabling readers to understand the research findings effectively. Different disciplines follow specific formats and citation styles, such as APA, MLA, Chicago, and IEEE. Knowing the requirements for each format ensures that researchers present their work in a professional and organized manner.

Why Research Paper Format is Important

- Consistency : A standardized format ensures that each paper has a similar structure, making it easier for readers to locate information.

- Credibility : Following a professional format enhances the credibility of the work, making it look polished and reliable.

- Guidelines for Citations : Proper format helps in organizing references and citing sources accurately, which is crucial for avoiding plagiarism.

- Reader Comprehension : An organized format improves readability, enabling readers to follow the research arguments and findings effortlessly.

Types of Research Paper Formats

1. apa format (american psychological association).

- Discipline : Commonly used in social sciences, psychology, education, and business.

- Title Page : Includes title, author’s name, affiliation, course, instructor, and date.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the research, usually around 150-250 words.

- Main Body : Contains sections such as introduction, method, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- References : Lists all sources cited in the paper in APA style.

- Double-spaced, Times New Roman 12-point font.

- One-inch margins on all sides.

- In-text citations include author’s last name and year (e.g., Smith, 2020).

2. MLA Format (Modern Language Association)

- Discipline : Commonly used in humanities, literature, and cultural studies.

- Header : Author’s name, instructor’s name, course, and date.

- Title : Centered on the first page, no separate title page required.

- Main Body : Sections for introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

- Works Cited : Lists all references in MLA style.

- One-inch margins, with in-text citations including the author’s last name and page number (e.g., Smith 45).

3. Chicago Format (Chicago Manual of Style)

- Discipline : Used in history, business, fine arts, and sometimes social sciences.

- Title Page : Includes the title, author’s name, and institutional affiliation.

- Abstract (Optional) : Brief summary, sometimes included depending on requirements.

- Main Body : Includes introduction, main sections, and conclusion.

- Footnotes/Endnotes : Citations are either in the form of footnotes or endnotes.

- Bibliography : Lists all sources in Chicago style.

- One-inch margins, with footnotes or endnotes for in-text citations.

4. IEEE Format (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

- Discipline : Primarily used in engineering, computer science, and technical fields.

- Title Page : Includes title, author’s name, affiliations, and acknowledgment.

- Abstract : Brief summary, typically 100-150 words.

- Main Body : Sections such as introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- References : Numbered list of references, with citations in brackets (e.g., [1], [2]).

- Double-column layout, single-spaced, Times New Roman 10-point font.

- One-inch margins, with citations indicated by numbers in brackets within the text.

5. Harvard Format

- Discipline : Widely used in academic publications, particularly in the UK.

- Title Page : Title, author’s name, date, and affiliation.

- Abstract : Summary of the research.

- Main Body : Sections such as introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- References : Alphabetized list in Harvard style.

- One-inch margins, with in-text citations including the author’s last name, year, and page number if applicable (e.g., Smith, 2020).

General Template for Research Paper

Here is a general template applicable across various formats, especially useful if a specific format isn’t required. Researchers can adjust sections based on the format style guide they need to follow.

- Paper Title

- Author’s Name(s)

- Institutional Affiliation

- Brief summary of the research, key findings, and significance.

- Typically 150-250 words.

- Background of the study and research questions.

- Purpose and significance of the research.

- Summary of existing research relevant to the topic.

- Identification of gaps in the literature.

- Detailed explanation of research methods and procedures.

- Description of sample, data collection, and analysis techniques.

- Presentation of findings, often with tables, charts, or graphs.

- Clear and objective reporting of data.

- Interpretation of findings.

- Comparison with other studies, implications, and potential limitations.

- Summary of the research and its contributions.

- Suggestions for future research.

- Complete list of all sources cited in the paper.

- Follow the specific citation style format (APA, MLA, etc.).

- Appendices (if required)

- Additional information, data, or materials relevant to the study but not included in the main text.

Tips for Formatting a Research Paper

- Check Formatting Guidelines : Each journal or institution may have specific requirements, so always refer to the official guidelines.

- Use Consistent Citations : Ensure all in-text citations and references follow the same format, matching the required style.

- Use Headings and Subheadings : Organize sections with clear headings to improve readability and structure.

- Proofread for Formatting Errors : Small formatting errors can detract from the professionalism of the paper, so carefully review layout and style.

- Use Templates in Word Processors : Many word processors offer built-in templates for APA, MLA, and other styles, helping streamline the formatting process.

Example of Research Paper Formatting in APA

Title Page Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Mental Health Author Name University Name Course Name, Instructor Name Date

Abstract This study explores the impact of social media use on adolescent mental health, focusing on levels of anxiety and depression. Data were collected from high school students through a survey. Results suggest a positive correlation between social media use and anxiety, highlighting the need for guidelines on healthy social media habits. (Word count: 150)

Main Body Introduction Discusses the background of social media’s popularity and its psychological effects on teenagers.

Methodology Details the survey process, sample selection, and data analysis techniques.

Results Presents survey findings on the levels of anxiety and depression associated with social media usage.

Discussion Interprets findings in light of previous research and discusses potential implications.

Conclusion Summarizes the key findings, suggesting areas for future study.

References Lists all references in APA format, alphabetically by author.

A research paper’s format is essential for presenting information clearly and professionally. By following specific guidelines, such as APA, MLA, or IEEE, researchers ensure that their work is accessible and credible. Using templates and formatting tips, researchers can structure their papers effectively, improving readability and impact.

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Gibaldi, J. (2016). MLA Handbook (8th ed.). Modern Language Association of America.

- University of Chicago Press. (2017). The Chicago Manual of Style (17th ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- IEEE Standards Association. (2020). IEEE Citation Reference . IEEE.

- Pears, R., & Shields, G. (2019). Cite Them Right: The Essential Referencing Guide . Red Globe Press.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

How to Publish a Research Paper – Step by Step...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Successful Scientific Writing and Publishing: A Step-by-Step Approach

John k iskander , md, mph, sara beth wolicki , mph, cph, rebecca t leeb , phd, paul z siegel , md, mph.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding Author: John Iskander, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd, NE, Atlanta, GA. Telephone: 404-639-8889. Email: [email protected] .

Corresponding author.

Collection date 2018.

This is a publication of the U.S. Government. This publication is in the public domain and is therefore without copyright. All text from this work may be reprinted freely. Use of these materials should be properly cited.

Scientific writing and publication are essential to advancing knowledge and practice in public health, but prospective authors face substantial challenges. Authors can overcome barriers, such as lack of understanding about scientific writing and the publishing process, with training and resources. The objective of this article is to provide guidance and practical recommendations to help both inexperienced and experienced authors working in public health settings to more efficiently publish the results of their work in the peer-reviewed literature. We include an overview of basic scientific writing principles, a detailed description of the sections of an original research article, and practical recommendations for selecting a journal and responding to peer review comments. The overall approach and strategies presented are intended to contribute to individual career development while also increasing the external validity of published literature and promoting quality public health science.

Introduction

Publishing in the peer-reviewed literature is essential to advancing science and its translation to practice in public health ( 1 , 2 ). The public health workforce is diverse and practices in a variety of settings ( 3 ). For some public health professionals, writing and publishing the results of their work is a requirement. Others, such as program managers, policy makers, or health educators, may see publishing as being outside the scope of their responsibilities ( 4 ).

Disseminating new knowledge via writing and publishing is vital both to authors and to the field of public health ( 5 ). On an individual level, publishing is associated with professional development and career advancement ( 6 ). Publications share new research, results, and methods in a trusted format and advance scientific knowledge and practice ( 1 , 7 ). As more public health professionals are empowered to publish, the science and practice of public health will advance ( 1 ).

Unfortunately, prospective authors face barriers to publishing their work, including navigating the process of scientific writing and publishing, which can be time-consuming and cumbersome. Often, public health professionals lack both training opportunities and understanding of the process ( 8 ). To address these barriers and encourage public health professionals to publish their findings, the senior author (P.Z.S.) and others developed Successful Scientific Writing (SSW), a course about scientific writing and publishing. Over the past 30 years, this course has been taught to thousands of public health professionals, as well as hundreds of students at multiple graduate schools of public health. An unpublished longitudinal survey of course participants indicated that two-thirds agreed that SSW had helped them to publish a scientific manuscript or have a conference abstract accepted. The course content has been translated into this manuscript. The objective of this article is to provide prospective authors with the tools needed to write original research articles of high quality that have a good chance of being published.

Basic Recommendations for Scientific Writing

Prospective authors need to know and tailor their writing to the audience. When writing for scientific journals, 4 fundamental recommendations are: clearly stating the usefulness of the study, formulating a key message, limiting unnecessary words, and using strategic sentence structure.

To demonstrate usefulness, focus on how the study addresses a meaningful gap in current knowledge or understanding. What critical piece of information does the study provide that will help solve an important public health problem? For example, if a particular group of people is at higher risk for a specific condition, but the magnitude of that risk is unknown, a study to quantify the risk could be important for measuring the population’s burden of disease.

Scientific articles should have a clear and concise take-home message. Typically, this is expressed in 1 to 2 sentences that summarize the main point of the paper. This message can be used to focus the presentation of background information, results, and discussion of findings. As an early step in the drafting of an article, we recommend writing out the take-home message and sharing it with co-authors for their review and comment. Authors who know their key point are better able to keep their writing within the scope of the article and present information more succinctly. Once an initial draft of the manuscript is complete, the take-home message can be used to review the content and remove needless words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Concise writing improves the clarity of an article. Including additional words or clauses can divert from the main message and confuse the reader. Additionally, journal articles are typically limited by word count. The most important words and phrases to eliminate are those that do not add meaning, or are duplicative. Often, cutting adjectives or parenthetical statements results in a more concise paper that is also easier to read.

Sentence structure strongly influences the readability and comprehension of journal articles. Twenty to 25 words is a reasonable range for maximum sentence length. Limit the number of clauses per sentence, and place the most important or relevant clause at the end of the sentence ( 9 ). Consider the sentences:

By using these tips and tricks, an author may write and publish an additional 2 articles a year.

An author may write and publish an additional 2 articles a year by using these tips and tricks.

The focus of the first sentence is on the impact of using the tips and tricks, that is, 2 more articles published per year. In contrast, the second sentence focuses on the tips and tricks themselves.

Authors should use the active voice whenever possible. Consider the following example:

Active voice: Authors who use the active voice write more clearly.

Passive voice: Clarity of writing is promoted by the use of the active voice.

The active voice specifies who is doing the action described in the sentence. Using the active voice improves clarity and understanding, and generally uses fewer words. Scientific writing includes both active and passive voice, but authors should be intentional with their use of either one.

Sections of an Original Research Article

Original research articles make up most of the peer-reviewed literature ( 10 ), follow a standardized format, and are the focus of this article. The 4 main sections are the introduction, methods, results, and discussion, sometimes referred to by the initialism, IMRAD. These 4 sections are referred to as the body of an article. Two additional components of all peer-reviewed articles are the title and the abstract. Each section’s purpose and key components, along with specific recommendations for writing each section, are listed below.

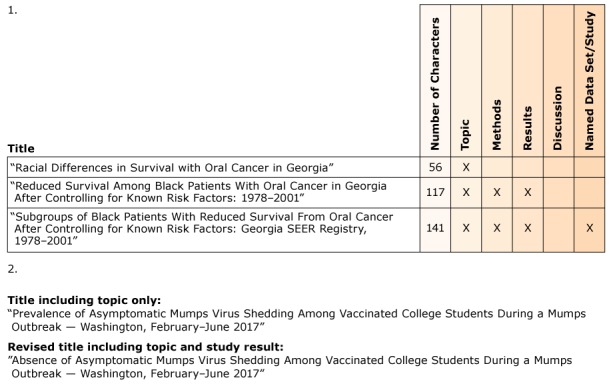

Title. The purpose of a title is twofold: to provide an accurate and informative summary and to attract the target audience. Both prospective readers and database search engines use the title to screen articles for relevance ( 2 ). All titles should clearly state the topic being studied. The topic includes the who, what, when, and where of the study. Along with the topic, select 1 or 2 of the following items to include within the title: methods, results, conclusions, or named data set or study. The items chosen should emphasize what is new and useful about the study. Some sources recommend limiting the title to less than 150 characters ( 2 ). Articles with shorter titles are more frequently cited than articles with longer titles ( 11 ). Several title options are possible for the same study ( Figure ).

Two examples of title options for a single study.

Abstract . The abstract serves 2 key functions. Journals may screen articles for potential publication by using the abstract alone ( 12 ), and readers may use the abstract to decide whether to read further. Therefore, it is critical to produce an accurate and clear abstract that highlights the major purpose of the study, basic procedures, main findings, and principal conclusions ( 12 ). Most abstracts have a word limit and can be either structured following IMRAD, or unstructured. The abstract needs to stand alone from the article and tell the most important parts of the scientific story up front.

Introduction . The purpose of the introduction is to explain how the study sought to create knowledge that is new and useful. The introduction section may often require only 3 paragraphs. First, describe the scope, nature, or magnitude of the problem being addressed. Next, clearly articulate why better understanding this problem is useful, including what is currently known and the limitations of relevant previous studies. Finally, explain what the present study adds to the knowledge base. Explicitly state whether data were collected in a unique way or obtained from a previously unstudied data set or population. Presenting both the usefulness and novelty of the approach taken will prepare the reader for the remaining sections of the article.

Methods . The methods section provides the information necessary to allow others, given the same data, to recreate the analysis. It describes exactly how data relevant to the study purpose were collected, organized, and analyzed. The methods section describes the process of conducting the study — from how the sample was selected to which statistical methods were used to analyze the data. Authors should clearly name, define, and describe each study variable. Some journals allow detailed methods to be included in an appendix or supplementary document. If the analysis involves a commonly used public health data set, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System ( 13 ), general aspects of the data set can be provided to readers by using references. Because what was done is typically more important than who did it, use of the passive voice is often appropriate when describing methods. For example, “The study was a group randomized, controlled trial. A coin was tossed to select an intervention group and a control group.”

Results . The results section describes the main outcomes of the study or analysis but does not interpret the findings or place them in the context of previous research. It is important that the results be logically organized. Suggested organization strategies include presenting results pertaining to the entire population first, and then subgroup analyses, or presenting results according to increasing complexity of analysis, starting with demographic results before proceeding to univariate and multivariate analyses. Authors wishing to draw special attention to novel or unexpected results can present them first.

One strategy for writing the results section is to start by first drafting the figures and tables. Figures, which typically show trends or relationships, and tables, which show specific data points, should each support a main outcome of the study. Identify the figures and tables that best describe the findings and relate to the study’s purpose, and then develop 1 to 2 sentences summarizing each one. Data not relevant to the study purpose may be excluded, summarized briefly in the text, or included in supplemental data sets. When finalizing figures, ensure that axes are labeled and that readers can understand figures without having to refer to accompanying text.

Discussion . In the discussion section, authors interpret the results of their study within the context of both the related literature and the specific scientific gap the study was intended to fill. The discussion does not introduce results that were not presented in the results section. One way authors can focus their discussion is to limit this section to 4 paragraphs: start by reinforcing the study’s take-home message(s), contextualize key results within the relevant literature, state the study limitations, and lastly, make recommendations for further research or policy and practice changes. Authors can support assertions made in the discussion with either their own findings or by referencing related research. By interpreting their own study results and comparing them to others in the literature, authors can emphasize findings that are unique, useful, and relevant. Present study limitations clearly and without apology. Finally, state the implications of the study and provide recommendations or next steps, for example, further research into remaining gaps or changes to practice or policy. Statements or recommendations regarding policy may use the passive voice, especially in instances where the action to be taken is more important than who will implement the action.

Beginning the Writing Process

The process of writing a scientific article occurs before, during, and after conducting the study or analyses. Conducting a literature review is crucial to confirm the existence of the evidence gap that the planned analysis seeks to fill. Because literature searches are often part of applying for research funding or developing a study protocol, the citations used in the grant application or study proposal can also be used in subsequent manuscripts. Full-text databases such as PubMed Central ( 14 ), NIH RePORT ( 15 ), and CDC Stacks ( 16 ) can be useful when performing literature reviews. Authors should familiarize themselves with databases that are accessible through their institution and any assistance that may be available from reference librarians or interlibrary loan systems. Using citation management software is one way to establish and maintain a working reference list. Authors should clearly understand the distinction between primary and secondary references, and ensure that they are knowledgeable about the content of any primary or secondary reference that they cite.

Review of the literature may continue while organizing the material and writing begins. One way to organize material is to create an outline for the paper. Another way is to begin drafting small sections of the article such as the introduction. Starting a preliminary draft forces authors to establish the scope of their analysis and clearly articulate what is new and novel about the study. Furthermore, using information from the study protocol or proposal allows authors to draft the methods and part of the results sections while the study is in progress. Planning potential data comparisons or drafting “table shells” will help to ensure that the study team has collected all the necessary data. Drafting these preliminary sections early during the writing process and seeking feedback from co-authors and colleagues may help authors avoid potential pitfalls, including misunderstandings about study objectives.

The next step is to conduct the study or analyses and use the resulting data to fill in the draft table shells. The initial results will most likely require secondary analyses, that is, exploring the data in ways in addition to those originally planned. Authors should ensure that they regularly update their methods section to describe all changes to data analysis.

After completing table shells, authors should summarize the key finding of each table or figure in a sentence or two. Presenting preliminary results at meetings, conferences, and internal seminars is an established way to solicit feedback. Authors should pay close attention to questions asked by the audience, treating them as an informal opportunity for peer review. On the basis of the questions and feedback received, authors can incorporate revisions and improvements into subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

The relevant literature should be revisited periodically while writing to ensure knowledge of the most recent publications about the manuscript topic. Authors should focus on content and key message during the process of writing the first draft and should not spend too much time on issues of grammar or style. Drafts, or portions of drafts, should be shared frequently with trusted colleagues. Their recommendations should be reviewed and incorporated when they will improve the manuscript’s overall clarity.

For most authors, revising drafts of the manuscript will be the most time-consuming task involved in writing a paper. By regularly checking in with coauthors and colleagues, authors can adopt a systematic approach to rewriting. When the author has completed a draft of the manuscript, he or she should revisit the key take-home message to ensure that it still matches the final data and analysis. At this point, final comments and approval of the manuscript by coauthors can be sought.

Authors should then seek to identify journals most likely to be interested in considering the study for publication. Initial questions to consider when selecting a journal include:

Which audience is most interested in the paper’s message?

Would clinicians, public health practitioners, policy makers, scientists, or a broader audience find this useful in their field or practice?

Do colleagues have prior experience submitting a manuscript to this journal?

Is the journal indexed and peer-reviewed?

Is the journal subscription or open-access and are there any processing fees?

How competitive is the journal?

Authors should seek to balance the desire to be published in a top-tier journal (eg, Journal of the American Medical Association, BMJ, or Lancet) against the statistical likelihood of rejection. Submitting the paper initially to a journal more focused on the paper’s target audience may result in a greater chance of acceptance, as well as more timely dissemination of findings that can be translated into practice. Most of the 50 to 75 manuscripts published each week by authors from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are published in specialty and subspecialty journals, rather than in top-tier journals ( 17 ).

The target journal’s website will include author guidelines, which will contain specific information about format requirements (eg, font, line spacing, section order, reference style and limit, table and figure formatting), authorship criteria, article types, and word limits for articles and abstracts.

We recommend returning to the previously drafted abstract and ensuring that it complies with the journal’s format and word limit. Authors should also verify that any changes made to the methods or results sections during the article’s drafting are reflected in the final version of the abstract. The abstract should not be written hurriedly just before submitting the manuscript; it is often apparent to editors and reviewers when this has happened. A cover letter to accompany the submission should be drafted; new and useful findings and the key message should be included.

Before submitting the manuscript and cover letter, authors should perform a final check to ensure that their paper complies with all journal requirements. Journals may elect to reject certain submissions on the basis of review of the abstract, or may send them to peer reviewers (typically 2 or 3) for consultation. Occasionally, on the basis of peer reviews, the journal will request only minor changes before accepting the paper for publication. Much more frequently, authors will receive a request to revise and resubmit their manuscript, taking into account peer review comments. Authors should recognize that while revise-and-resubmit requests may state that the manuscript is not acceptable in its current form, this does not constitute a rejection of the article. Authors have several options in responding to peer review comments:

Performing additional analyses and updating the article appropriately

Declining to perform additional analyses, but providing an explanation (eg, because the requested analysis goes beyond the scope of the article)

Providing updated references

Acknowledging reviewer comments that are simply comments without making changes

In addition to submitting a revised manuscript, authors should include a cover letter in which they list peer reviewer comments, along with the revisions they have made to the manuscript and their reply to the comment. The tone of such letters should be thankful and polite, but authors should make clear areas of disagreement with peer reviewers, and explain why they disagree. During the peer review process, authors should continue to consult with colleagues, especially ones who have more experience with the specific journal or with the peer review process.

There is no secret to successful scientific writing and publishing. By adopting a systematic approach and by regularly seeking feedback from trusted colleagues throughout the study, writing, and article submission process, authors can increase their likelihood of not only publishing original research articles of high quality but also becoming more scientifically productive overall.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge PCD ’s former Associate Editor, Richard A. Goodman, MD, MPH, who, while serving as Editor in Chief of CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Series, initiated a curriculum on scientific writing for training CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers and other CDC public health professionals, and with whom the senior author of this article (P.Z.S.) collaborated in expanding training methods and contents, some of which are contained in this article. The authors acknowledge Juan Carlos Zevallos, MD, for his thoughtful critique and careful editing of previous Successful Scientific Writing materials. We also thank Shira Eisenberg for editorial assistance with the manuscript. This publication was supported by the Cooperative Agreement no. 1U360E000002 from CDC and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. The findings and conclusions of this article do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Names of journals and citation databases are provided for identification purposes only and do not constitute any endorsement by CDC.

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions.

Suggested citation for this article: Iskander JK, Wolicki SB, Leeb RT, Siegel PZ. Successful Scientific Writing and Publishing: A Step-by-Step Approach. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:180085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180085 .

- 1. Azer SA, Dupras DM, Azer S. Writing for publication in medical education in high impact journals. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18(19):2966–81. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Vitse CL, Poland GA. Writing a scientific paper — a brief guide for new investigators. Vaccine 2017;35(5):722–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.091 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Sellers K, Leider JP, Harper E, Castrucci BC, Bharthapudi K, Liss-Levinson R, et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey: the first national survey of state health agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015;21(Suppl 6):S13–27. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Salas-Lopez D, Deitrick L, Mahady ET, Moser K, Gertner EJ, Sabino JN. Getting published in an academic-community hospital: the success of writing groups. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(1):113–6. 10.1007/s11606-011-1872-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Azer SA, Ramani S, Peterson R. Becoming a peer reviewer to medical education journals. Med Teach 2012;34(9):698–704. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687488 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Baldwin C, Chandler GE. Improving faculty publication output: the role of a writing coach. J Prof Nurs 2002;18(1):8–15. 10.1053/jpnu.2002.30896 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Nicholas D, Watkinson A, Jamali H, Herman E, Tenopir C, Volentine R, et al. Peer review: still king in the digital age. Learn Publ 2015;28(1):15–21. 10.1087/20150104 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Crowson MG. A crash course in medical writing for health profession students. J Cancer Educ 2013;28(3):554–7. 10.1007/s13187-013-0502-0 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Gopen GD, Swan JA. The science of scientific writing. Am Sci 1990;78(6):550–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ecarnot F, Seronde MF, Chopard R, Schiele F, Meneveau N. Writing a scientific article: a step-by-step guide for beginners. Eur Geriatr Med 2015;6(6):573–9. 10.1016/j.eurger.2015.08.005 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Letchford A, Moat HS, Preis T. The advantage of short paper titles. R Soc Open Sci 2015;2(8):150266. 10.1098/rsos.150266 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Groves T, Abbasi K. Screening research papers by reading abstracts. BMJ 2004;329(7464):470–1. 10.1136/bmj.329.7464.470 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Xu F, Mawokomatanda T, Flegel D, Pierannunzi C, Garvin W, Chowdhury P, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for certain health behaviors among states and selected local areas — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014;63(9):1–149. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. PubMed Central https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ . Accessed April 22, 2018.

- 15. National Institutes of Health Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) https://report.nih.gov/ .Accessed April 25, 2018.

- 16. CDC Stacks. https://stacks.cdc.gov/welcome . Accessed April 25, 2018.

- 17. Iskander J, Bang G, Stupp E, Connick K, Gomez O, Gidudu J. Articles Published and Downloaded by Public Health Scientists: Analysis of Data From the CDC Public Health Library, 2011-2013. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22(4):409–14. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000277 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (292.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

%PDF-1.6 %âãÏÓ 912 0 obj > endobj 924 0 obj >/Filter/FlateDecode/ID[]/Index[912 27]/Info 911 0 R/Length 74/Prev 1734110/Root 913 0 R/Size 939/Type/XRef/W[1 2 1 ...

Dec 1, 2015 · Many young researchers find it extremely difficult to write scientific articles, and few receive specific training in the art of presenting their research work in written format. Yet, publication is often vital for career advancement, to obtain funding, to obtain academic qualifications, or for all these reasons.

Keywords: paper format, scientific writing. FORMATTING TIPS: Check whether "Keywords" should be italicized and whether each term should be capitalized. Check the use of punctuation (e.g., commas versus semicolons, the use of the period at the end). Some journals (e.g., IEEE) provide a taxonomy of keywords. This aids in the classification of ...

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings”, but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice.

writing a scientific article. This guide describes the purpose, content and writing style for each of the sections of a typical scientific article. Additionally, examples of well-written parts of each section of a sample article are provided. Read this entire guide before you begin writing the first draft of your research article.

Mar 26, 2024 · Proofread for Formatting Errors: Small formatting errors can detract from the professionalism of the paper, so carefully review layout and style. Use Templates in Word Processors: Many word processors offer built-in templates for APA, MLA, and other styles, helping streamline the formatting process. Example of Research Paper Formatting in APA

Scientific writing includes both active and passive voice, but authors should be intentional with their use of either one. Sections of an Original Research Article. Original research articles make up most of the peer-reviewed literature , follow a standardized format, and are the focus of this article. The 4 main sections are the introduction ...

As we've discussed, all introductions begin broadly. The audience, format, and purpose of your paper influence how broad it should be. You can expect more background knowledge from readers of a technical journal than you can from readers of a popular magazine. Use a ‘hook’ to capture readers’ interest.

Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. A standard format is used for these articles, in which the author presents the research in an orderly, logical manner. This doesn't necessarily reflect the order in which you did or thought about the work. This ...

Avoid: "We ran a model simulation of the ocean for research into the evolution of the thermocline." Write: "We ran an ocean model simulation to conduct research into thermocline evolution." Run-on prepositional phrases are awkward to read. They can rapidly lead to reader fatigue. Avoid subjective or redundant words or phrases that