Characteristics & Qualities of a Good Hypothesis

A good hypothesis possesses the following certain attributes.

Power of Prediction

One of the valuable attribute of a good hypothesis is to predict for future. It not only clears the present problematic situation but also predict for the future that what would be happened in the coming time. So, hypothesis is a best guide of research activity due to power of prediction.

Closest to observable things

A hypothesis must have close contact with observable things. It does not believe on air castles but it is based on observation. Those things and objects which we cannot observe, for that hypothesis cannot be formulated. The verification of a hypothesis is based on observable things.

A hypothesis should be so dabble to every layman, P.V young says, “A hypothesis wo0uld be simple, if a researcher has more in sight towards the problem”. W-ocean stated that, “A hypothesis should be as sharp as razor’s blade”. So, a good hypothesis must be simple and have no complexity.

A hypothesis must be conceptually clear. It should be clear from ambiguous information’s. The terminology used in it must be clear and acceptable to everyone.

Testability

A good hypothesis should be tested empirically. It should be stated and formulated after verification and deep observation. Thus testability is the primary feature of a good hypothesis.

Relevant to Problem

If a hypothesis is relevant to a particular problem, it would be considered as good one. A hypothesis is guidance for the identification and solution of the problem, so it must be accordance to the problem.

It should be formulated for a particular and specific problem. It should not include generalization. If generalization exists, then a hypothesis cannot reach to the correct conclusions.

Relevant to available Techniques

Hypothesis must be relevant to the techniques which is available for testing. A researcher must know about the workable techniques before formulating a hypothesis.

Fruitful for new Discoveries

It should be able to provide new suggestions and ways of knowledge. It must create new discoveries of knowledge J.S. Mill, one of the eminent researcher says that “Hypothesis is the best source of new knowledge it creates new ways of discoveries”.

Consistency & Harmony

Internal harmony and consistency is a major characteristic of good hypothesis. It should be out of contradictions and conflicts. There must be a close relationship between variables which one is dependent on other.

Related Articles

Kinds of Legislation, Supreme Legislation & Subordinate Legislation

The Best PhD and Masters Consulting Company

Characteristics Of A Good Hypothesis

What exactly is a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a conclusion reached after considering the evidence. This is the first step in any investigation, where the research questions are translated into a prediction. Variables, population, and the relationship between the variables are all included. A research hypothesis is a hypothesis that is tested to see if two or more variables have a relationship. Now let’s have a look at the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Characteristics of

A good hypothesis has the following characteristics.

Ability To Predict

Closest to things that can be seen, testability, relevant to the issue, techniques that are applicable, new discoveries have been made as a result of this ., harmony & consistency.

- The similarity between the two phenomena.

- Observations from previous studies, current experiences, and feedback from rivals.

- Theories based on science.

- People’s thinking processes are influenced by general patterns.

- A straightforward hypothesis

- Complex Hypothesis

- Hypothesis with a certain direction

- Non-direction Hypothesis

- Null Hypothesis

- Hypothesis of association and chance

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Your Article Library

Conditions for a valid hypothesis: 5 conditions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This article throws light on the five important conditions for a valid hypothesis.

1. The most essential condition for a valid hypothesis is that it should be capable of empirical verification, so that it has to be ultimately confirmed or refuted. Otherwise it will remain a proposition only. Therefore it should be formulated in such a way that it is possible to deduce certain inferences which in turn can be tested by observation in the field. It should not be a mere moral judgment.

As the basis of objectivity, the most essential condition of scientific method, empirical test, concerning the verification of facts and figures enables generalizations which do not differ from person to person. The concepts incorporated in the hypothesis should be explicitly defined and must have unambiguous empirical correspondence.

2. Secondly, the hypothesis must be conceptually clear, definite and certain. It should not be vague or ambiguous. It should be properly expressed. The concepts should not only be formally defined in a clear-cut manner, but also operationally. If a hypothesis is loaded with un-defined or ill-defined concepts, it moves beyond empirical test because, understandably, there is no standard basis for cognizing what observable facts would constitute its test.

Hypotheses stated in vague terms do not lead anywhere. Therefore, while formulating the hypothesis, the researcher should take care to incorporate such concepts which are not only commonly accepted, but also communicable so that it would ensure continuity in research.

3. Thirdly, hypothesis must be specific and predictions indicated should be spelled out. A general hypothesis has limited scope in the sense that it may only serve as an indicator of an area of investigation rather than serving the hypothesis. A hypothesis of grandiose scope is simply not amenable to test. Narrower hypothesis involves a degree of humility and specific hypothesis is of any real use. A hypothesis must provide answer to the problem which initiated enquiry.

4. Fourthly, the possibility of actually testing the hypothesis can be approved. A hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that its conceptual content can be easily translated to understand the observable reality. If the hypothesis is not the closest to things observable, it would not be possible to test their accord with empirical facts.

The concepts involved in the hypothesis should be such that the possibility of generating operational definitions can be ensured and deductions can be made. According to Cohen and Nagel, “hypothesis must be formulated in such a manner that deductions can be made from it and consequently, a decision can be reached as to whether it does or does not explain the facts considered.”

5. Fifthly, the hypothesis should be related to a body of theory and should possess theoretical relevance. It must provide theoretical rationale by seeking answer to question as to what will be the theoretical gains of testing the hypothesis? If the hypothesis is derived from a theory, research will enable to confirm support, correct or refute the theory.

Science, being the constant interplay of theory and fact, gains immensely from such testing’s. If the hypotheses are selected at random and in piece meal, they cannot be studied in relation to broader theoretical framework. In the words of Goode and Hatt “When research is systematically, based upon a body of existing theory, a genuine contribution is more likely to result. In other words, to be worth doing a hypothesis must not only be carefully stated, but it should possess theoretical relevance.”

Finally, the hypothesis should be related to available techniques. The hypothesis, in order to be workable, should be capable of being tested and measured to existing methods and techniques of scientific nature. According to Goode and Hatt, “the theories who do not know what techniques are available to test hypothesis is a “poor way to formulate usable question.”.

On the contrary, if a new or original theory is in the process of evolution, it would make the work of the investigator easier for propounding a new theory. In this regard, Goode and Hatt have correctly stated, “In many serious sociological discussions research frontiers are continuously challenged by the assertion that various problems ought to be investigated even though the investigations are presently impossible.”

Knowledge of the available techniques at the time of formulations of hypothesis is merely a sensible requirement which applies to any problem in its earlier stages in order to judge its research ability. But “this is not be taken on absolute injunction against the formulation of hypothesis which at present are too complex to be handled by the contemporary technique.”

Related Articles:

- Role of Hypothesis in Social Research

- Hypothesis: Meaning, Criteria for Formulation and it’s Types

Comments are closed.

Product Talk

Make better product decisions.

The 5 Components of a Good Hypothesis

Originally published: November 12, 2014 by Teresa Torres | Last updated: December 7, 2018

Update: I’ve since revised this hypothesis format. You can find the most current version in this article:

- How to Improve Your Experiment Design (And Build Trust in Your Product Experiments)

“My hypothesis is …”

These words are becoming more common everyday. Product teams are starting to talk like scientists. Are you?

The internet industry is going through a mindset shift. Instead of assuming we have all the right answers, we are starting to acknowledge that building products is hard. We are accepting the reality that our ideas are going to fail more often than they are going to succeed.

Rather than waiting to find out which ideas are which after engineers build them, smart product teams are starting to integrate experimentation into their product discovery process. They are asking themselves, how can we test this idea before we invest in it?

This process starts with formulating a good hypothesis.

These Are Not the Hypotheses You Are Looking For

When we are new to hypothesis testing, we tend to start with hypotheses like these:

- Fixing the hard-to-use comment form will increase user engagement.

- A redesign will improve site usability.

- Reducing prices will make customers happy.

There’s only one problem. These aren’t testable hypotheses. They aren’t specific enough.

A good hypothesis can be clearly refuted or supported by an experiment. – Tweet This

To make sure that your hypotheses can be supported or refuted by an experiment, you will want to include each of these elements:

- the change that you are testing

- what impact we expect the change to have

- who you expect it to impact

- by how much

- after how long

The Change: This is the change that you are introducing to your product. You are testing a new design, you are adding new copy to a landing page, or you are rolling out a new feature.

Be sure to get specific. Fixing a hard-to-use comment form is not specific enough. How will you fix it? Some solutions might work. Others might not. Each is a hypothesis in its own right.

Design changes can be particularly challenging. Your hypothesis should cover a specific design not the idea of a redesign.

In other words, use this:

- This specific design will increase conversions.

- Redesigning the landing page will increase conversions.

The former can be supported or refuted by an experiment. The latter can encompass dozens of design solutions, where some might work and others might not.

The Expected Impact: The expected impact should clearly define what you expect to see as a result of making the change.

How will you know if your change is successful? Will it reduce response times, increase conversions, or grow your audience?

The expected impact needs to be specific and measurable. – Tweet This

You might hypothesize that your new design will increase usability. This isn’t specific enough.

You need to define how you will measure an increase in usability. Will it reduce the time to complete some action? Will it increase customer satisfaction? Will it reduce bounce rates?

There are dozens of ways that you might measure an increase in usability. In order for this to be a testable hypothesis, you need to define which metric you expect to be affected by this change.

Who Will Be Impacted: The third component of a good hypothesis is who will be impacted by this change. Too often, we assume everyone. But this is rarely the case.

I was recently working with a product manager who was testing a sign up form popup upon exiting a page.

I’m sure you’ve seen these before. You are reading a blog post and just as you are about to navigate away, you get a popup that asks, “Would you like to subscribe to our newsletter?”

She A/B tested this change by showing it to half of her population, leaving the rest as her control group. But there was a problem.

Some of her visitors were already subscribers. They don’t need to subscribe again. For this population, the answer to this popup will always be no.

Rather than testing with her whole population, she should be testing with just the people who are not currently subscribers.

This isn’t easy to do. And it might not sound like it’s worth the effort, but it’s the only way to get good results.

Suppose she has 100 visitors. Fifty see the popup and fifty don’t. If 45 of the people who see the popup are already subscribers and as a result they all say no, and of the five remaining visitors only 1 says yes, it’s going to look like her conversion rate is 1 out of 50, or 2%. However, if she limits her test to just the people who haven’t subscribed, her conversion rate is 1 out of 5, or 20%. This is a huge difference.

Who you test with is often the most important factor for getting clean results. – Tweet This

By how much: The fourth component builds on the expected impact. You need to define how much of an impact you expect your change to have.

For example, if you are hypothesizing that your change will increase conversion rates, then you need to estimate by how much, as in the change will increase conversion rate from x% to y%, where x is your current conversion rate and y is your expected conversion rate after making the change.

This can be hard to do and is often a guess. However, you still want to do it. It serves two purposes.

First, it helps you draw a line in the sand. This number should determine in black and white terms whether or not your hypothesis passes or fails and should dictate how you act on the results.

Suppose you hypothesize that the change will improve conversion rates by 10%, then if your change results in a 9% increase, your hypothesis fails.

This might seem extreme, but it’s a critical step in making sure that you don’t succumb to your own biases down the road.

It’s very easy after the fact to determine that 9% is good enough. Or that 2% is good enough. Or that -2% is okay, because you like the change. Without a line in the sand, you are setting yourself up to ignore your data.

The second reason why you need to define by how much is so that you can calculate for how long to run your test.

After how long: Too many teams run their tests for an arbitrary amount of time or stop the results when one version is winning.

This is a problem. It opens you up to false positives and releasing changes that don’t actually have an impact.

If you hypothesize the expected impact ahead of time than you can use a duration calculator to determine for how long to run the test.

Finally, you want to add the duration of the test to your hypothesis. This will help to ensure that everyone knows that your results aren’t valid until the duration has passed.

If your traffic is sporadic, “how long” doesn’t have to be defined in time. It can also be defined in page views or sign ups or after a specific number of any event.

Putting It All Together

Use the following examples as templates for your own hypotheses:

- Design x [the change] will increase conversions [the impact] for search campaign traffic [the who] by 10% [the how much] after 7 days [the how long].

- Reducing the sign up steps from 3 to 1 will increase signs up by 25% for new visitors after 1,000 visits to the sign up page.

- This subject line will increase open rates for daily digest subscribers by 15% after 3 days.

After you write a hypothesis, break it down into its five components to make sure that you haven’t forgotten anything.

- Change: this subject line

- Impact: will increase open rates

- Who: for daily digest subscribers

- By how much: by 15%

- After how long: After 3 days

And then ask yourself:

- Is your expected impact specific and measurable?

- Can you clearly explain why the change will drive the expected impact?

- Are you testing with the right population?

- Did you estimate your how much based on a baseline and / or comparable changes? (more on this in a future post)

- Did you calculate the duration using a duration calculator?

It’s easy to give lip service to experimentation and hypothesis testing. But if you want to get the most out of your efforts, make sure you are starting with a good hypothesis.

Did you learn something new reading this article? Keep learning. Subscribe to the Product Talk mailing list to get the next article in this series delivered to your inbox.

Get the latest from Product Talk right in your inbox.

Join 41,000+ product people. Never miss an article.

May 21, 2017 at 2:11 am

Interesting article, I am thinking about making forming a hypothesis around my product, if certain customers will find a proposed value useful. Can you kindly let me know if I’m on the right track.

“Certain customer segment (AAA) will find value in feature (XXX), to tackle their pain point ”

Change: using a feature (XXX)/ product Impact: will reduce monetary costs/ help solve a problem Who: for certain customers segment (AAA) By how much: by 5% After how long: 10 days

April 4, 2020 at 12:33 pm

Hi! Could you throw a little light on this: “Suppose you hypothesize that the change will improve conversion rates by 10%, then if your change results in a 9% increase, your hypothesis fails.”

I understood the rationale behind having a number x (10% in this case) associated with “by how much”, but could you explain with an example of how to ballpark a figure like this?

Popular Resources

- Product Discovery Basics: Everything You Need to Know

- Product Trios: What They Are, Why They Matter, and How to Get Started

- Visualize Your Thinking with Opportunity Solution Trees

- Shifting from Outputs to Outcomes: Why It Matters and How to Get Started

- Customer Interviews: How to Recruit, What to Ask, and How to Synthesize What You Learn

- Assumption Testing: Everything You Need to Know to Get Started

Recent Posts

- 2025 Product Conference List

- Join 4 Upcoming Events on Continuous Discovery with Teresa Torres in December 2024

- Product in Practice: Mapping Business and Product Outcomes to Stand Out in the Job Search

- Ask Teresa: Does the Engineer in the Product Trio Need to be the Tech Lead?

- Customer Recruiting for Continuous Discovery: Get Easy Access to Customers Week Over Week

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Subject index

In an increasingly data-driven world, it is more important than ever for students as well as professionals to better understand basic statistical concepts. 100 Questions (and Answers) About Statistics addresses the essential questions that students ask about statistics in a concise and accessible way. It is perfect for instructors, students, and practitioners as a supplement to more comprehensive materials, or as a desk reference with quick answers to the most frequently asked questions.

What Are the Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis?

- By: Neil J. Salkind

- In: 100 Questions (and Answers) About Statistics

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781483372334.n61

- Subject: Engineering , Mathematics

- Keywords: students

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

A well-written and well-thought-out hypothesis can make all the difference between a successful and unsuccessful research effort. This is primarily because a well-written hypothesis reflects a well-conceived research project based on an adequate review of the literature and a logical proposition about the relationship between variables.

Here is a summary of the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

First, a good hypothesis is stated in declarative form and not as a question. For example, “Are retention rates for first-year students at state universities low because students run out of money?” could, with some review of the literature, become, “Retention rates for first-year students at state universities are lower than the average because students cannot afford to return for the second semester due to a shortage of funds.” The hypothesis becomes a direct and clear statement.

Second, a good hypothesis proposes a relationship between variables. In the example we just provided, the variables are whether or not the student remains in school (retention) and the reason for not remaining in school if the student leaves. In this example, the idea that is being tested is that new students do not remain in school because school becomes too expensive.

Third, a good hypothesis reflects the literature or the results of previous studies on which the hypothesis is based. This is where good old-fashioned detective work at the library or online provides the information needed to best understand the possible relationships that might be found and their importance to the overall research mission.

Fourth, a good hypothesis is brief and to the point. It is not a review of the literature or a rationale for the hypothesis itself. Rather it is a concise and clear statement of the relationship between variables such that any other person with some familiarity with the subject matter could read the hypothesis and fully understand the central purpose of the research study.

Finally, a good hypothesis is testable. The variables are clearly understood, as is their proposed relationship. In our example, the central question is the relationship between continued enrollment in school and why [Page 126] that may not occur. The hypothesis narrows that question to look specifically at one reason why continued enrollment may not occur. Given the way the hypothesis is stated, it allows the question to be tested and the results and new knowledge gained to be applied to the next hypothesis and subsequent testing.

More questions? See questions #60 , #63 , and #64 .

What Is a Hypothesis, and Why Is It Important in Scientific Research?

How Do a Sample and a Population Differ From One Another?

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

- Classification

- Physical Education

- Travel and Tourism

- BIBLIOMETRICS

- Banking System

- Real Estate

Select Page

Hypothesis | Definitions, Functions, Characteristics, Types, Errors & The Process of Testing a Hypothesis | Hypotheses in Qualitative Research

Posted by Md. Harun Ar Rashid | Apr 20, 2022 | Research Methodology

Hypotheses bring clarity, specificity, and focus to a research problem. It is not essential for a study and one can conduct a valid investigation without constructing a formal hypothesis. On the other hand, within the context of a research study, we can construct as many hypotheses as we consider to be appropriate. Hypotheses primarily arise from a set of ‘hunches’ that are tested through a study and one can conduct a perfectly valid study without having these hunches or speculations. Hypotheses are based upon similar logic. As a researcher, we do not know about a phenomenon, a situation, the prevalence of a condition in a population, or the outcome of a program, but we do have a hunch to form the basis of certain assumptions or guesses. We test these, mostly one by one, by collecting information that will enable us to conclude if our hunch was right. The verification process can have one of three outcomes. Our hunch may prove to be: right, partially right, or wrong. Without this process of verification, we cannot conclude anything about the validity of our assumption. In the rest of the article, we are going to present to you definitions, functions, characteristics, types, errors & the process of testing a hypothesis, and hypotheses in qualitative research.

Definitions of Hypothesis:

A hypothesis is a hunch, assumption, suspicion, assertion, or an idea about a phenomenon, relationship, or situation, the reality or truth of which we do not know.

A researcher calls these assumptions, assertions, statements, or hunches hypotheses and they become the basis of an inquiry.

In most studies, the hypothesis will be based upon either previous studies or our own or someone else’s observations.

“A hypothesis is a conjectural statement of the relationship between two or more variables.” ( Kerlinger, 1986)

Black and Champion define a hypothesis as “a tentative statement about something, the validity of which is usually unknown”

Bailey defines a hypothesis as; a proposition that is stated in a testable form and that predicts a particular relationship between two (or more) variables.

“A hypothesis is written in such a way that it can be proven or disproven by valid and reliable data – it is in order to obtain these data that we perform our study.” ( Grinnell, 2013 )

From the above definitions it is apparent that a hypothesis has certain characteristics:

- It is a tentative proposition.

- Its validity is unknown.

- In most cases, it specifies a relationship between two or more variables.

Functions of a Hypothesis:

A hypothesis is important in terms of bringing clarity to the research problem. Specifically, a hypothesis serves the following functions:

- A hypothesis provides a study with focus. It tells us what specific aspects of a research problem to investigate.

- It tells us what data to collect and what not to collect, thereby providing focus to the study.

- As it provides a focus, the construction of a hypothesis enhances objectivity.

- A hypothesis may enable us to add to the formulation of the theory. It enables us to conclude specifically what is true or what is false.

Characteristics of a Hypothesis:

There are a number of considerations to keep in mind when constructing a hypothesis. The wording of a hypothesis must have certain attributes that make it easier for us to ascertain its validity. These attributes are:

- A hypothesis should be simple, specific, and conceptually clear. There is no place for ambiguity in the construction of a hypothesis, as ambiguity will make the verification of a hypothesis almost impossible.

- It should be ‘unidimensional’ – that is, it should test only one relationship or hunch at a time.

- To be able to develop a good hypothesis we must be familiar with the subject area. The more insight we have into a problem, the easier it is to construct a hypothesis.

For example; the average age of the male students in this class is higher than that of the female students. The above hypothesis is clear, specific, and easy to test. It tells us what we are attempting to compare (average age of this class), which population groups are being compared (female and male students), and what we want to establish (higher average age of the male students).

Let us take another example; suicide rates vary inversely with social cohesion. (Black & Champion 1976) This hypothesis is clear and specific, but a lot more difficult to test. There are three aspects of this hypothesis: ‘suicide rates’; ‘vary inversely’, which stipulates the direction of the relationship; and ‘social cohesion. Finding out the suicide rates and establishing whether the relationship is inverse or otherwise are comparatively easy, but ascertaining social cohesion is a lot more difficult. What determines social cohesion? How can it be measured? This problem makes it difficult to test this hypothesis.

- A hypothesis should be capable of verification. Methods and techniques must be available for data collection and analysis.

- A hypothesis should be related to the existing body of knowledge.

- It is important that our hypothesis emerges from the existing body of knowledge, and that it adds to it, as this is an important function of research.

- This can only be achieved if the hypothesis has its roots in the existing body of knowledge.

- A hypothesis should be operationalizable. This means that it can be expressed in terms that can be measured. If it cannot be measured, it cannot be tested and, hence, no conclusions can be drawn.

Types of Hypothesis:

Theoretically, there should be only one type of hypothesis which is the research hypothesis – the basis of our investigation. However, because of the conventions in scientific inquiries and because of the wording used in the construction of a hypothesis, hypotheses can be classified into several types. Broadly, there are two categories of hypotheses: Research hypotheses and Alternate hypotheses.

Formulation of an alternate hypothesis is a convention in scientific circles. Its function is to explicitly specify the relationship that will be considered as true in case the research hypothesis proves to be wrong. An alternate hypothesis is the opposite of the research hypothesis. Conventionally, a null hypothesis, or hypothesis of no difference, is formulated as an alternate hypothesis.

Let us take an example; suppose we want to test the effect that different combinations of maternal and child health services (MCH) and nutritional supplements (NS) have on the infant mortality rate. To test this, a two-by-two factorial experimental design is adopted.

The second hypothesis in each example implies that there is a difference either in the extent of the impact of different treatment modalities on infant mortality or in the proportion of male and female smokers among the population, though the extent of the difference is not specified. A hypothesis in which a researcher stipulates that there will be a difference but does not specify its magnitude is called a hypothesis of difference.

Let us take an example; suppose we want to study the smoking pattern in a community in relation to gender differentials. The following hypotheses could be constructed:

- There is no significant difference in the proportion of male and female smokers in the study population.

- A greater proportion of females than males are smokers in the study population.

- A total of 60 percent of females and 30 percent of males in the study population are smokers.

- There are twice as many female smokers as male smokers in the study population.

In the examples, the way the first hypothesis has been formulated indicates that there is no difference either in the extent of the impact of different treatment modalities on the infant mortality rate or in the proportion of male and female smokers.

When we construct a hypothesis stipulating that there is no difference between two situations, groups, outcomes, or the prevalence of a condition or phenomenon, this is called a null hypothesis and is usually written as H0.

The Process of Testing a Hypothesis:

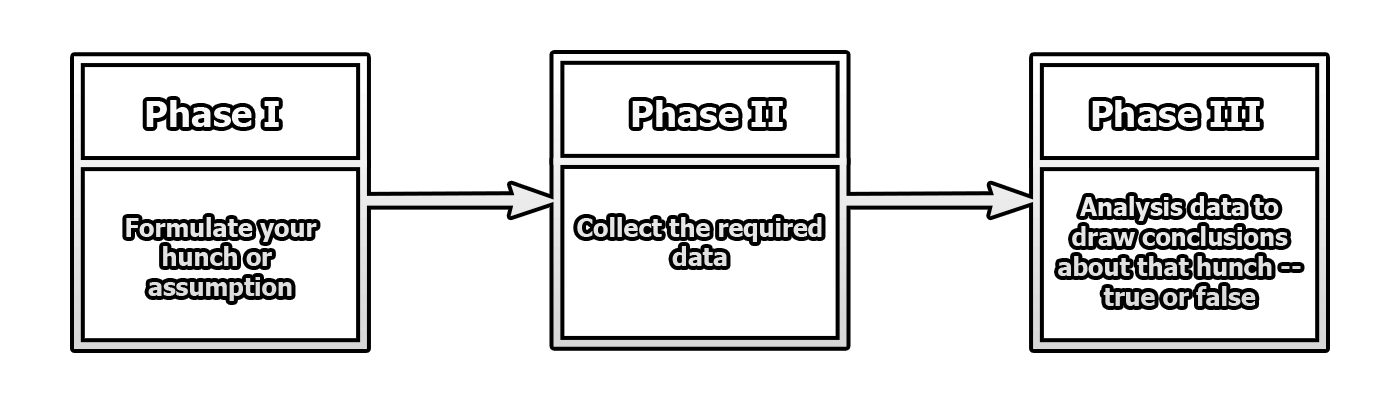

To test a hypothesis, we need to go through a process that comprises three phases:

- Constructing a hypothesis;

- Gathering appropriate evidence; and

- Analyzing evidence to draw conclusions as to its validity.

It is only after analyzing the evidence that we can conclude whether our hunch or hypothesis was true or false. In conclusion, we specifically make a statement about the correctness or otherwise of a hypothesis in the form of ‘the hypothesis is true or ‘the hypothesis is false’. It is, therefore, imperative that we formulate our hypotheses clearly, precisely, and in a form that is testable. In making a conclusion about the validity of a hypothesis, the way we collect our evidence is of central importance and it is therefore essential that our study design, sample, data collection method(s), data analysis and conclusions, and communication of the conclusions be valid, appropriate and free from any bias.

Errors in Testing a Hypothesis:

As already mentioned, a hypothesis is an assumption that may prove to be either correct or incorrect. It is possible to arrive at an incorrect conclusion about a hypothesis for a variety of reasons. Incorrect conclusions about the validity of a hypothesis may be drawn if:

- The study design selected is faulty;

- The sampling procedure adopted is faulty;

- The method of data collection is inaccurate;

- The analysis is wrong;

- The statistical procedures applied are inappropriate; or

- The conclusions drawn are incorrect.

Any, some or all of these aspects of the research process could be responsible for the inadvertent introduction of error in a study, making conclusions misleading. Hence, in the testing hypothesis, there is always the possibility of errors attributable to the reasons identified above. In drawing conclusions about a hypothesis, two types of error can occur:

- Rejection of a null hypothesis when it is true. This is known as a Type I error.

- Acceptance of a null hypothesis when it is false. This is known as a Type II error.

Hypotheses in Qualitative Research:

- One of the differences in qualitative and quantitative research is around the importance attached to and the extent of use of hypotheses in undertaking a study.

- As qualitative studies pay emphasis on describing, understanding, and exploring phenomena using categorical and subjective measurement procedures, the construction of hypotheses is neither advocated nor practiced.

- In addition, as the degree of specificity needed to test a hypothesis is deliberately not adhered to in qualitative research, the testing of a hypothesis becomes difficult and meaningless.

- It does not mean that we cannot construct hypotheses in qualitative research; the non-specificity of the problem as well as methods and procedures make the convention of hypotheses formulation far less practicable and advisable.

- Even within quantitative studies, the importance attached to and the practice of formulating hypotheses vary markedly from one academic discipline to another.

- In social sciences, the formulation of hypotheses is mostly dependent on the researcher and the academic discipline, whereas within an academic discipline it varies markedly between the quantitative and qualitative research paradigms.

References:

- Kerlinger, P., & Lein, M. R. (1986). Differences in Winter Range among age-sex Classes of Snowy Owls Nyctea scandiaca in North America. Ornis Scandinavica (Scandinavian Journal of Ornithology) , 17 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/3676745

- Black, J. A., & Champion, D. J. (1976). Methods and issues in social research . John Wiley & Sons.

- Bailey, K. D. (2006). Living systems theory and social entropy theory. Systems Research and Behavioral Science: The Official Journal of the International Federation for Systems Research , 23 (3), 291-300.

- Grinnell, F. (2013). Research integrity and everyday practice of science. Science and Engineering Ethics , 19 (3), 685-701. The Process Testing of a Hypothesis The Process Testing of a Hypothesis The Process Testing of a Hypothesis

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College

About The Author

Md. Harun Ar Rashid

Related posts.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Archival Research

December 4, 2023

Formulating a Research Problem | Importance, Sources, Considerations in Selecting, and Steps in Formulating a Research Problem | Formulation of Research Objectives

September 26, 2022

Research Constructs | Examples of Research Constructs | Construct Validity and Reliability | Research Construct vs Variable

April 2, 2023

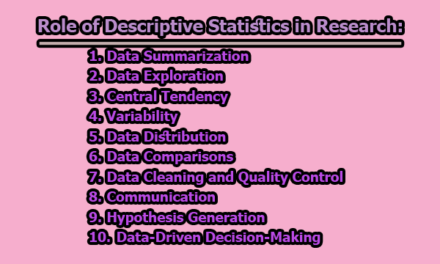

Role of Descriptive Statistics in Research

October 21, 2023

Follow us on Facebook

Library & Information Management Community

Recent Posts

Pin It on Pinterest

- LiveJournal

2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A hypothesis should be so dabble to every layman, P.V young says, "A hypothesis wo0uld be simple, if a researcher has more in sight towards the problem". W-ocean stated that, "A hypothesis should be as sharp as razor's blade". So, a good hypothesis must be simple and have no complexity. Clarity. A hypothesis must be conceptually clear.

Characteristics of Hypothesis. A good hypothesis has the following characteristics. Ability To Predict One of the most valuable qualities of a good hypothesis is the ability to anticipate the future. It not only clarifies the current problematic scenario, but also predicts what will happen in the future. As a result of the predictive capacity ...

ADVERTISEMENTS: This article throws light on the five important conditions for a valid hypothesis. 1. The most essential condition for a valid hypothesis is that it should be capable of empirical verification, so that it has to be ultimately confirmed or refuted. Otherwise it will remain a proposition only. Therefore it should be formulated in […]

This process starts with formulating a good hypothesis. These Are Not the Hypotheses You Are Looking For. When we are new to hypothesis testing, we tend to start with hypotheses like these: Fixing the hard-to-use comment form will increase user engagement. A redesign will improve site usability. Reducing prices will make customers happy.

This is primarily because a well-written hypothesis reflects a well-conceived research project based on an adequate review of the literature and a logical proposition about the relationship between variables. Here is a summary of the characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis is stated in declarative form and not as a question.

"A hypothesis is written in such a way that it can be proven or disproven by valid and reliable data - it is in order to obtain these data that we perform our study." (Grinnell, 2013) ... Characteristics of a Hypothesis: There are a number of considerations to keep in mind when constructing a hypothesis. The wording of a hypothesis must ...

The main characteristics of the hypothesis are as below. The most important condition for a valid hypothesis is that it should be empirically verified. A hypothesis ultimately has to confirm or ...

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis. There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable. We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you'll recall Popper's falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm ...

Dig Deeper: Defining Hypothesis. A key concept to experimental data is the hypothesis. While we will go more in depth into how to handle a hypothesis and the characteristics of a good hypothesis in Chapter 9, Hypothetico-deductive Research, it is important that we define it now to help guide you in determining an appropriate research method.

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. Explore examples and learn how to format your research hypothesis. ... In the scientific method, falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.