ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The importance of students’ motivation for their academic achievement – replicating and extending previous findings.

- 1 Department of Psychology, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany

- 2 Department of Psychology, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 3 Department of Psychology, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Achievement motivation is not a single construct but rather subsumes a variety of different constructs like ability self-concepts, task values, goals, and achievement motives. The few existing studies that investigated diverse motivational constructs as predictors of school students’ academic achievement above and beyond students’ cognitive abilities and prior achievement showed that most motivational constructs predicted academic achievement beyond intelligence and that students’ ability self-concepts and task values are more powerful in predicting their achievement than goals and achievement motives. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the reported previous findings can be replicated when ability self-concepts, task values, goals, and achievement motives are all assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria (e.g., hope for success in math and math grades). The sample comprised 345 11th and 12th grade students ( M = 17.48 years old, SD = 1.06) from the highest academic track (Gymnasium) in Germany. Students self-reported their ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives in math, German, and school in general. Additionally, we assessed their intelligence and their current and prior Grade point average and grades in math and German. Relative weight analyses revealed that domain-specific ability self-concept, motives, task values and learning goals but not performance goals explained a significant amount of variance in grades above all other predictors of which ability self-concept was the strongest predictor. Results are discussed with respect to their implications for investigating motivational constructs with different theoretical foundation.

Introduction

Achievement motivation energizes and directs behavior toward achievement and therefore is known to be an important determinant of academic success (e.g., Robbins et al., 2004 ; Hattie, 2009 ; Plante et al., 2013 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Achievement motivation is not a single construct but rather subsumes a variety of different constructs like motivational beliefs, task values, goals, and achievement motives (see Murphy and Alexander, 2000 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Nevertheless, there is still a limited number of studies, that investigated (1) diverse motivational constructs in relation to students’ academic achievement in one sample and (2) additionally considered students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). Because students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement are among the best single predictors of academic success (e.g., Kuncel et al., 2004 ; Hailikari et al., 2007 ), it is necessary to include them in the analyses when evaluating the importance of motivational factors for students’ achievement. Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) did so and revealed that students’ domain-specific ability self-concepts followed by domain-specific task values were the best predictors of students’ math and German grades compared to students’ goals and achievement motives. However, a flaw of their study is that they did not assess all motivational constructs at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. For example, achievement motives were measured on a domain-general level (e.g., “Difficult problems appeal to me”), whereas students’ achievement as well as motivational beliefs and task values were assessed domain-specifically (e.g., math grades, math self-concept, math task values). The importance of students’ achievement motives for math and German grades might have been underestimated because the specificity levels of predictor and criterion variables did not match (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977 ; Baranik et al., 2010 ). The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the seminal findings by Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) will hold when motivational beliefs, task values, goals, and achievement motives are all assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. This is an important question with respect to motivation theory and future research in this field. Moreover, based on the findings it might be possible to better judge which kind of motivation should especially be fostered in school to improve achievement. This is important information for interventions aiming at enhancing students’ motivation in school.

Theoretical Relations Between Achievement Motivation and Academic Achievement

We take a social-cognitive approach to motivation (see also Pintrich et al., 1993 ; Elliot and Church, 1997 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). This approach emphasizes the important role of students’ beliefs and their interpretations of actual events, as well as the role of the achievement context for motivational dynamics (see Weiner, 1992 ; Pintrich et al., 1993 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). Social cognitive models of achievement motivation (e.g., expectancy-value theory by Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ; hierarchical model of achievement motivation by Elliot and Church, 1997 ) comprise a variety of motivation constructs that can be organized in two broad categories (see Pintrich et al., 1993 , p. 176): students’ “beliefs about their capability to perform a task,” also called expectancy components (e.g., ability self-concepts, self-efficacy), and their “motivational beliefs about their reasons for choosing to do a task,” also called value components (e.g., task values, goals). The literature on motivation constructs from these categories is extensive (see Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). In this article, we focus on selected constructs, namely students’ ability self-concepts (from the category “expectancy components of motivation”), and their task values and goal orientations (from the category “value components of motivation”).

According to the social cognitive perspective, students’ motivation is relatively situation or context specific (see Pintrich et al., 1993 ). To gain a comprehensive picture of the relation between students’ motivation and their academic achievement, we additionally take into account a traditional personality model of motivation, the theory of the achievement motive ( McClelland et al., 1953 ), according to which students’ motivation is conceptualized as a relatively stable trait. Thus, we consider the achievement motives hope for success and fear of failure besides students’ ability self-concepts, their task values, and goal orientations in this article. In the following, we describe the motivation constructs in more detail.

Students’ ability self-concepts are defined as cognitive representations of their ability level ( Marsh, 1990 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Ability self-concepts have been shown to be domain-specific from the early school years on (e.g., Wigfield et al., 1997 ). Consequently, they are frequently assessed with regard to a certain domain (e.g., with regard to school in general vs. with regard to math).

In the present article, task values are defined in the sense of the expectancy-value model by Eccles et al. (1983) and Eccles and Wigfield (2002) . According to the expectancy-value model there are three task values that should be positively associated with achievement, namely intrinsic values, utility value, and personal importance ( Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ). Because task values are domain-specific from the early school years on (e.g., Eccles et al., 1993 ; Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ), they are also assessed with reference to specific subjects (e.g., “How much do you like math?”) or on a more general level with regard to school in general (e.g., “How much do you like going to school?”).

Students’ goal orientations are broader cognitive orientations that students have toward their learning and they reflect the reasons for doing a task (see Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ). Therefore, they fall in the broad category of “value components of motivation.” Initially, researchers distinguished between learning and performance goals when describing goal orientations ( Nicholls, 1984 ; Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ). Learning goals (“task involvement” or “mastery goals”) describe people’s willingness to improve their skills, learn new things, and develop their competence, whereas performance goals (“ego involvement”) focus on demonstrating one’s higher competence and hiding one’s incompetence relative to others (e.g., Elliot and McGregor, 2001 ). Performance goals were later further subdivided into performance-approach (striving to demonstrate competence) and performance-avoidance goals (striving to avoid looking incompetent, e.g., Elliot and Church, 1997 ; Middleton and Midgley, 1997 ). Some researchers have included work avoidance as another component of achievement goals (e.g., Nicholls, 1984 ; Harackiewicz et al., 1997 ). Work avoidance refers to the goal of investing as little effort as possible ( Kumar and Jagacinski, 2011 ). Goal orientations can be assessed in reference to specific subjects (e.g., math) or on a more general level (e.g., in reference to school in general).

McClelland et al. (1953) distinguish the achievement motives hope for success (i.e., positive emotions and the belief that one can succeed) and fear of failure (i.e., negative emotions and the fear that the achievement situation is out of one’s depth). According to McClelland’s definition, need for achievement is measured by describing affective experiences or associations such as fear or joy in achievement situations. Achievement motives are conceptualized as being relatively stable over time. Consequently, need for achievement is theorized to be domain-general and, thus, usually assessed without referring to a certain domain or situation (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). However, Sparfeldt and Rost (2011) demonstrated that operationalizing achievement motives subject-specifically is psychometrically useful and results in better criterion validities compared with a domain-general operationalization.

Empirical Evidence on the Relative Importance of Achievement Motivation Constructs for Academic Achievement

A myriad of single studies (e.g., Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2018 ; Muenks et al., 2018 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ) and several meta-analyses (e.g., Robbins et al., 2004 ; Möller et al., 2009 ; Hulleman et al., 2010 ; Huang, 2011 ) support the hypothesis of social cognitive motivation models that students’ motivational beliefs are significantly related to their academic achievement. However, to judge the relative importance of motivation constructs for academic achievement, studies need (1) to investigate diverse motivational constructs in one sample and (2) to consider students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement, too, because the latter are among the best single predictors of academic success (e.g., Kuncel et al., 2004 ; Hailikari et al., 2007 ). For effective educational policy and school reform, it is crucial to obtain robust empirical evidence for whether various motivational constructs can explain variance in school performance over and above intelligence and prior achievement. Without including the latter constructs, we might overestimate the importance of motivation for achievement. Providing evidence that students’ achievement motivation is incrementally valid in predicting their academic achievement beyond their intelligence or prior achievement would emphasize the necessity of designing appropriate interventions for improving students’ school-related motivation.

There are several studies that included expectancy and value components of motivation as predictors of students’ academic achievement (grades or test scores) and additionally considered students’ prior achievement ( Marsh et al., 2005 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 , Study 1) or their intelligence ( Spinath et al., 2006 ; Lotz et al., 2018 ; Schneider et al., 2018 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 , Study 2, Weber et al., 2013 ). However, only few studies considered intelligence and prior achievement together with more than two motivational constructs as predictors of school students’ achievement ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). Kriegbaum et al. (2015) examined two expectancy components (i.e., ability self-concept and self-efficacy) and eight value components (i.e., interest, enjoyment, usefulness, learning goals, performance-approach, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance) in the domain of math. Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) investigated the role of an expectancy component (i.e., ability self-concept), five value components (i.e., task values, learning goals, performance-approach, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance), and students’ achievement motives (i.e., hope for success, fear of failure, and need for achievement) for students’ grades in math and German and their GPA. Both studies used relative weights analyses to compare the predictive power of all variables simultaneously while taking into account multicollinearity of the predictors ( Johnson and LeBreton, 2004 ; Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2011 ). Findings showed that – after controlling for differences in students‘ intelligence and their prior achievement – expectancy components (ability self-concept, self-efficacy) were the best motivational predictors of achievement followed by task values (i.e., intrinsic/enjoyment, attainment, and utility), need for achievement and learning goals ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). However, Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) who investigated the relations in three different domains did not assess all motivational constructs on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. More precisely, students’ achievement as well as motivational beliefs and task values were assessed domain-specifically (e.g., math grades, math self-concept, math task values), whereas students’ goals were only measured for school in general (e.g., “In school it is important for me to learn as much as possible”) and students’ achievement motives were only measured on a domain-general level (e.g., “Difficult problems appeal to me”). Thus, the importance of goals and achievement motives for math and German grades might have been underestimated because the specificity levels of predictor and criterion variables did not match (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977 ; Baranik et al., 2010 ). Assessing students’ goals and their achievement motives with reference to a specific subject might result in higher associations with domain-specific achievement criteria (see Sparfeldt and Rost, 2011 ).

Taken together, although previous work underlines the important roles of expectancy and value components of motivation for school students’ academic achievement, hitherto, we know little about the relative importance of expectancy components, task values, goals, and achievement motives in different domains when all of them are assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria (e.g., achievement motives in math → math grades; ability self-concept for school → GPA).

The Present Research

The goal of the present study was to examine the relative importance of several of the most important achievement motivation constructs in predicting school students’ achievement. We substantially extend previous work in this field by considering (1) diverse motivational constructs, (2) students’ intelligence and their prior achievement as achievement predictors in one sample, and (3) by assessing all predictors on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. Moreover, we investigated the relations in three different domains: school in general, math, and German. Because there is no study that assessed students’ goal orientations and achievement motives besides their ability self-concept and task values on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria, we could not derive any specific hypotheses on the relative importance of these constructs, but instead investigated the following research question (RQ):

RQ. What is the relative importance of students’ domain-specific ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives for their grades in the respective domain when including all of them, students’ intelligence and prior achievement simultaneously in the analytic models?

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure.

A sample of 345 students was recruited from two German schools attending the highest academic track (Gymnasium). Only 11th graders participated at one school, whereas 11th and 12th graders participated at the other. Students of the different grades and schools did not differ significantly on any of the assessed measures. Students represented the typical population of this type of school in Germany; that is, the majority was Caucasian and came from medium to high socioeconomic status homes. At the time of testing, students were on average 17.48 years old ( SD = 1.06). As is typical for this kind of school, the sample comprised more girls ( n = 200) than boys ( n = 145). We verify that the study is in accordance with established ethical guidelines. Approval by an ethics committee was not required as per the institution’s guidelines and applicable regulations in the federal state where the study was conducted. Participation was voluntarily and no deception took place. Before testing, we received written informed consent forms from the students and from the parents of the students who were under the age of 18 on the day of the testing. If students did not want to participate, they could spend the testing time in their teacher’s room with an extra assignment. All students agreed to participate. Testing took place during regular classes in schools in 2013. Tests were administered by trained research assistants and lasted about 2.5 h. Students filled in the achievement motivation questionnaires first, and the intelligence test was administered afterward. Before the intelligence test, there was a short break.

Ability Self-Concept

Students’ ability self-concepts were assessed with four items per domain ( Schöne et al., 2002 ). Students indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) how good they thought they were at different activities in school in general, math, and German (“I am good at school in general/math/German,” “It is easy to for me to learn in school in general/math/German,” “In school in general/math/German, I know a lot,” and “Most assignments in school/math/German are easy for me”). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the ability self-concept scale was high in school in general, in math, and in German (0.82 ≤ α ≤ 0.95; see Table 1 ).

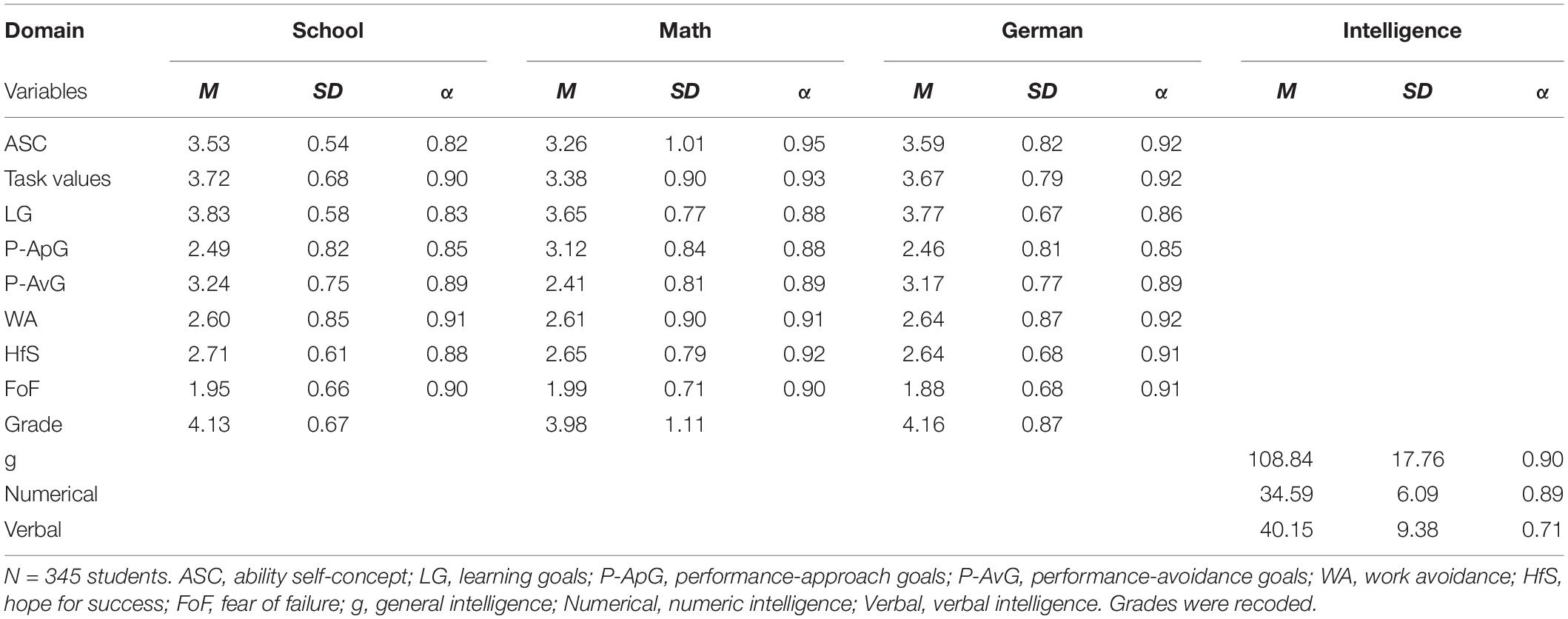

Table 1. Means ( M ), Standard Deviations ( SD ), and Reliabilities (α) for all measures.

Task Values

Students’ task values were assessed with an established German scale (SESSW; Subjective scholastic value scale; Steinmayr and Spinath, 2010 ). The measure is an adaptation of items used by Eccles and Wigfield (1995) in different studies. It assesses intrinsic values, utility, and personal importance with three items each. Students indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) how much they valued school in general, math, and German (Intrinsic values: “I like school/math/German,” “I enjoy doing things in school/math/German,” and “I find school in general/math/German interesting”; Utility: “How useful is what you learn in school/math/German in general?,” “School/math/German will be useful in my future,” “The things I learn in school/math/German will be of use in my future life”; Personal importance: “Being good at school/math/German is important to me,” “To be good at school/math/German means a lot to me,” “Attainment in school/math/German is important to me”). Internal consistency of the values scale was high in all domains (0.90 ≤ α ≤ 0.93; see Table 1 ).

Goal Orientations

Students’ goal orientations were assessed with an established German self-report measure (SELLMO; Scales for measuring learning and achievement motivation; Spinath et al., 2002 ). In accordance with Sparfeldt et al. (2007) , we assessed goal orientations with regard to different domains: school in general, math, and German. In each domain, we used the SELLMO to assess students’ learning goals, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance with eight items each and their performance-approach goals with seven items. Students’ answered the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). All items except for the work avoidance items are printed in Spinath and Steinmayr (2012) , p. 1148). A sample item to assess work avoidance is: “In school/math/German, it is important to me to do as little work as possible.” Internal consistency of the learning goals scale was high in all domains (0.83 ≤ α ≤ 0.88). The same was true for performance-approach goals (0.85 ≤ α ≤ 0.88), performance-avoidance goals (α = 0.89), and work avoidance (0.91 ≤ α ≤ 0.92; see Table 1 ).

Achievement Motives

Achievement motives were assessed with the Achievement Motives Scale (AMS; Gjesme and Nygard, 1970 ; Göttert and Kuhl, 1980 ). In the present study, we used a short form measuring “hope for success” and “fear of failure” with the seven items per subscale that showed the highest factor loadings. Both subscales were assessed in three domains: school in general, math, and German. Students’ answered all items on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (fully applies). An example hope for success item is “In school/math/German, difficult problems appeal to me,” and an example fear of failure item is “In school/math/German, matters that are slightly difficult disconcert me.” Internal consistencies of hope for success and fear of failure scales were high in all domains (hope for success: 0.88 ≤ α ≤ 0.92; fear of failure: 0.90 ≤ α ≤ 0.91; see Table 1 ).

Intelligence

Intelligence was measured with the basic module of the Intelligence Structure Test 2000 R, a well-established German multifactor intelligence measure (I-S-T 2000 R; Amthauer et al., 2001 ). The basic module of the test offers assessments of domain-specific intelligence for verbal, numeric, and figural abilities as well as an overall intelligence score (a composite of the three facets). The overall intelligence score is thought to measure reasoning as a higher order factor of intelligence and can be interpreted as a measure of general intelligence, g . Its construct validity has been demonstrated in several studies ( Amthauer et al., 2001 ; Steinmayr and Amelang, 2006 ). In the present study, we used the scores that were closest to the domains we investigated: overall intelligence, numerical intelligence, and verbal intelligence (see also Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). Raw values could range from 0 to 60 for verbal and numerical intelligence, and from 0 to 180 for overall intelligence. Internal consistencies of all intelligence scales were high (0.71 ≤ α ≤ 0.90; see Table 1 ).

Academic Achievement

For all students, the school delivered the report cards that the students received 3 months before testing (t0) and 4 months after testing (t2), at the end of the term in which testing took place. We assessed students’ grades in German and math as well as their overall grade point average (GPA) as criteria for school performance. GPA was computed as the mean of all available grades, not including grades in the nonacademic domains Sports and Music/Art as they did not correlate with the other grades. Grades ranged from 1 to 6, and were recoded so that higher numbers represented better performance.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted relative weight analyses to predict students’ academic achievement separately in math, German, and school in general. The relative weight analysis is a statistical procedure that enables to determine the relative importance of each predictor in a multiple regression analysis (“relative weight”) and to take adequately into account the multicollinearity of the different motivational constructs (for details, see Johnson and LeBreton, 2004 ; Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2011 ). Basically, it uses a variable transformation approach to create a new set of predictors that are orthogonal to one another (i.e., uncorrelated). Then, the criterion is regressed on these new orthogonal predictors, and the resulting standardized regression coefficients can be used because they no longer suffer from the deleterious effects of multicollinearity. These standardized regression weights are then transformed back into the metric of the original predictors. The rescaled relative weight of a predictor can easily be transformed into the percentage of variance that is uniquely explained by this predictor when dividing the relative weight of the specific predictor by the total variance explained by all predictors in the regression model ( R 2 ). We performed the relative weight analyses in three steps. In Model 1, we included the different achievement motivation variables assessed in the respective domain in the analyses. In Model 2, we entered intelligence into the analyses in addition to the achievement motivation variables. In Model 3, we included prior school performance indicated by grades measured before testing in addition to all of the motivation variables and intelligence. For all three steps, we tested for whether all relative weight factors differed significantly from each other (see Johnson, 2004 ) to determine which motivational construct was most important in predicting academic achievement (RQ).

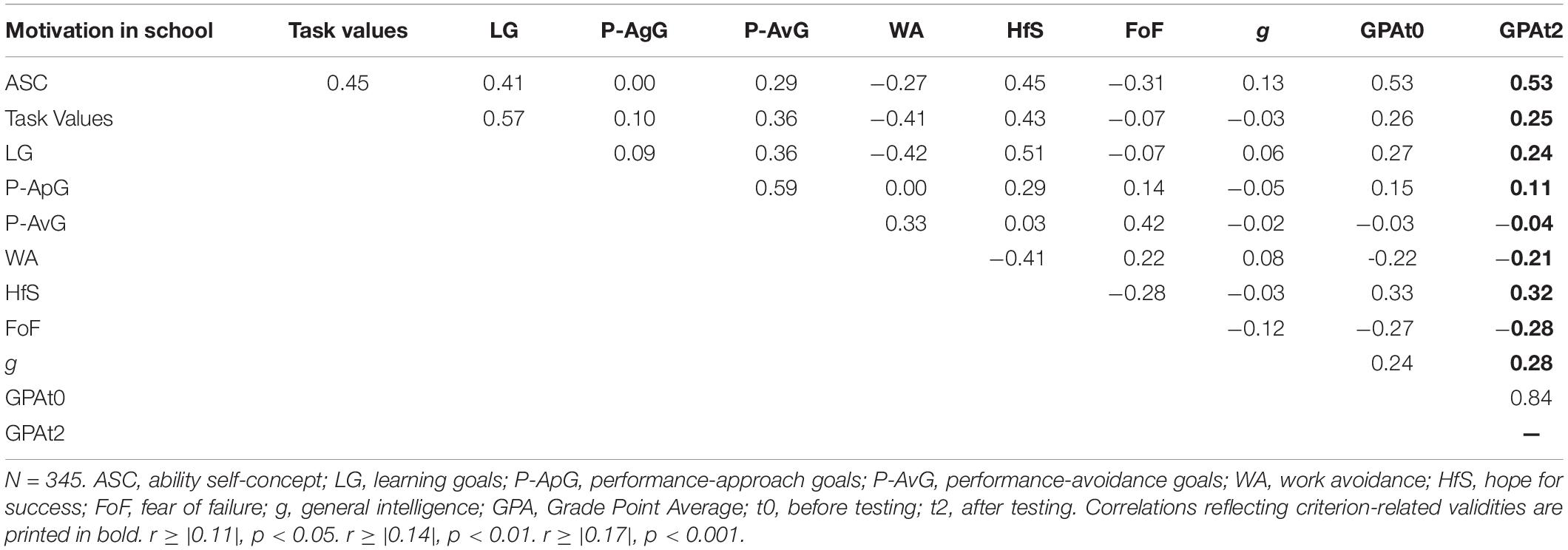

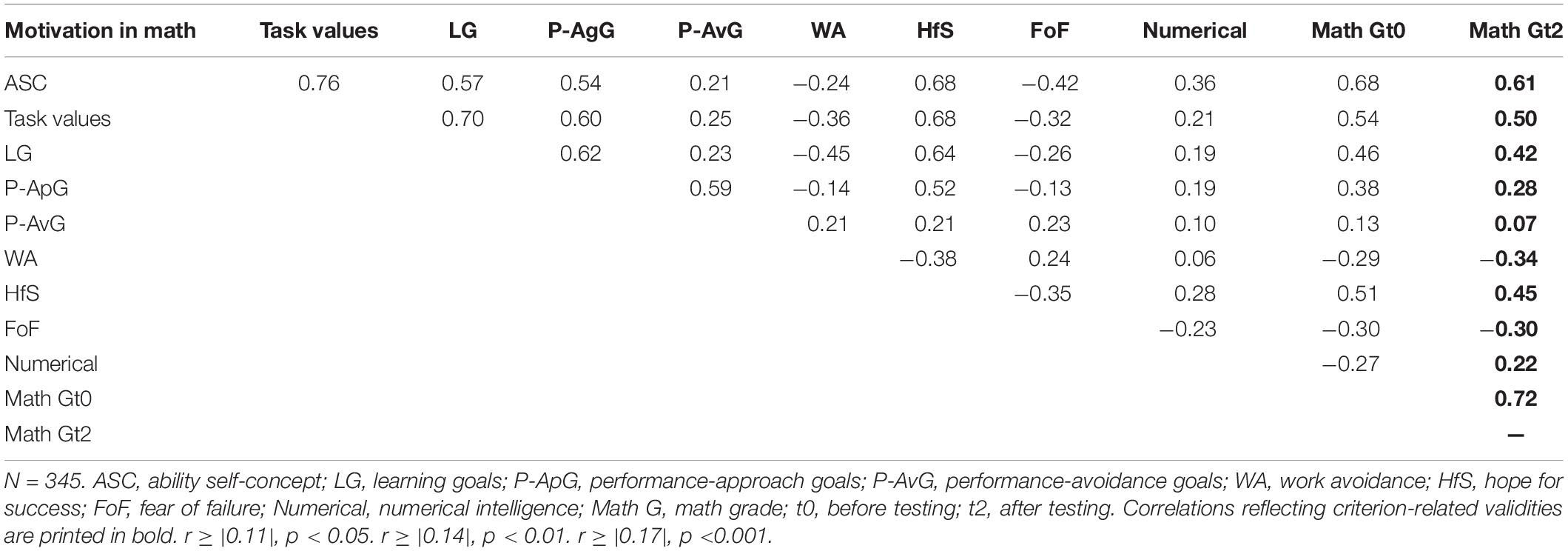

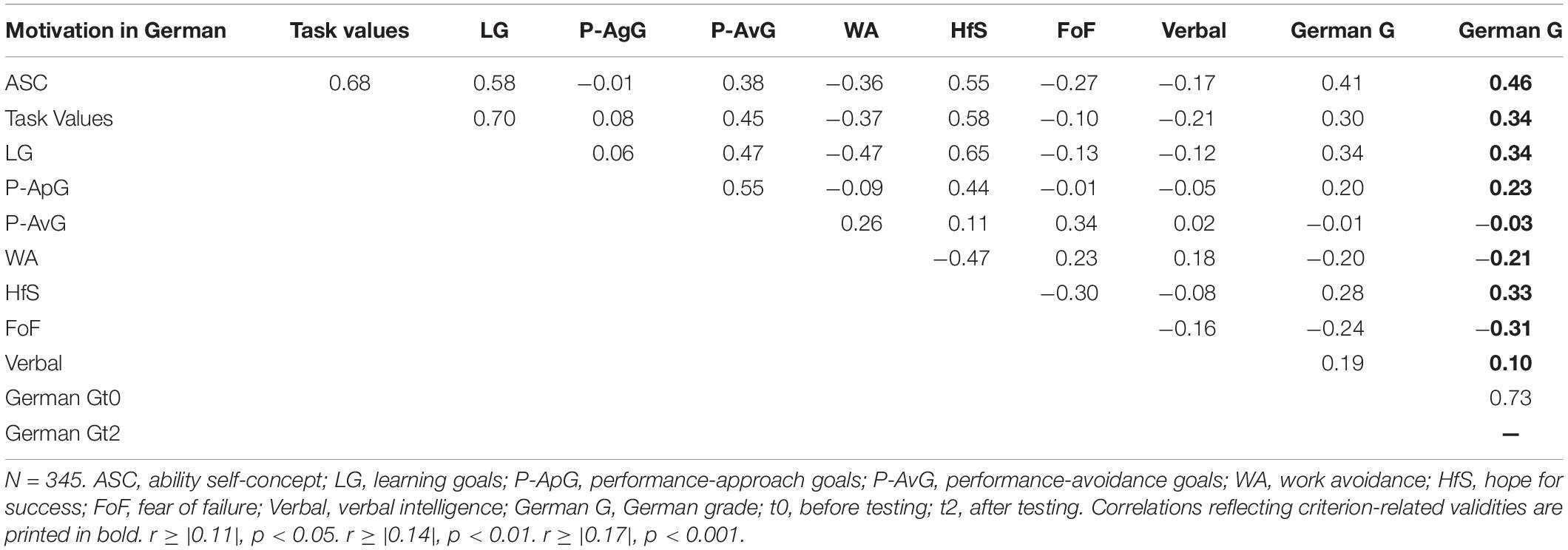

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and reliabilities. Tables 2 –4 show the correlations between all scales in school in general, in math, and in German. Of particular relevance here, are the correlations between the motivational constructs and students’ school grades. In all three domains (i.e., school in general/math/German), out of all motivational predictor variables, students’ ability self-concepts showed the strongest associations with subsequent grades ( r = 0.53/0.61/0.46; see Tables 2 –4 ). Except for students’ performance-avoidance goals (−0.04 ≤ r ≤ 0.07, p > 0.05), the other motivational constructs were also significantly related to school grades. Most of the respective correlations were evenly dispersed around a moderate effect size of | r | = 0.30.

Table 2. Intercorrelations between all variables in school in general.

Table 3. Intercorrelations between all variables in math.

Table 4. Intercorrelations between all variables in German.

Relative Weight Analyses

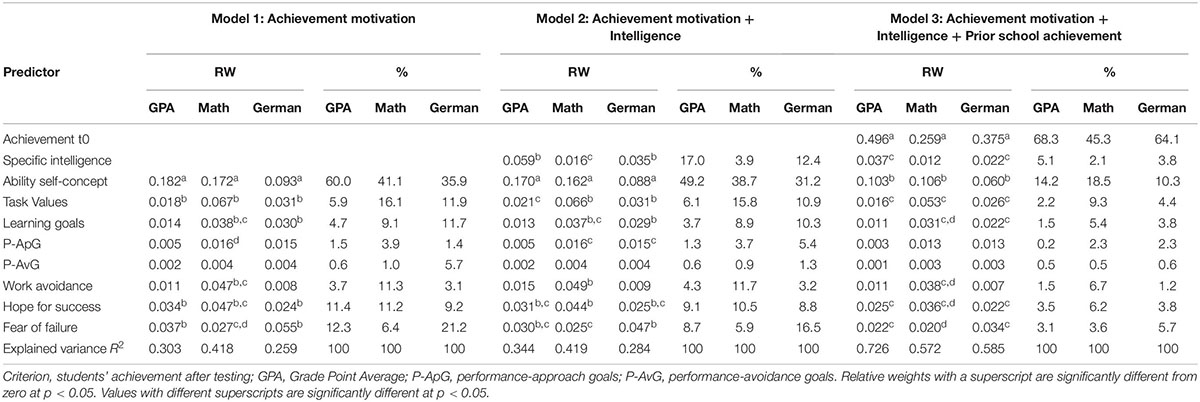

Table 5 presents the results of the relative weight analyses. In Model 1 (only motivational variables) and Model 2 (motivation and intelligence), respectively, the overall explained variance was highest for math grades ( R 2 = 0.42 and R 2 = 0.42, respectively) followed by GPA ( R 2 = 0.30 and R 2 = 0.34, respectively) and grades in German ( R 2 = 0.26 and R 2 = 0.28, respectively). When prior school grades were additionally considered (Model 3) the largest amount of variance was explained in students’ GPA ( R 2 = 0.73), followed by grades in German ( R 2 = 0.59) and math ( R 2 = 0.57). In the following, we will describe the results of Model 3 for each domain in more detail.

Table 5. Relative weights and percentages of explained criterion variance (%) for all motivational constructs (Model 1) plus intelligence (Model 2) plus prior school achievement (Model 3).

Beginning with the prediction of students’ GPA: In Model 3, students’ prior GPA explained more variance in subsequent GPA than all other predictor variables (68%). Students’ ability self-concept explained significantly less variance than prior GPA but still more than all other predictors that we considered (14%). The relative weights of students’ intelligence (5%), task values (2%), hope for success (4%), and fear of failure (3%) did not differ significantly from each other but were still significantly different from zero ( p < 0.05). The relative weights of students’ goal orientations were not significant in Model 3.

Turning to math grades: The findings of the relative weight analyses for the prediction of math grades differed slightly from the prediction of GPA. In Model 3, the relative weights of numerical intelligence (2%) and performance-approach goals (2%) in math were no longer different from zero ( p > 0.05); in Model 2 they were. Prior math grades explained the largest share of the unique variance in subsequent math grades (45%), followed by math self-concept (19%). The relative weights of students’ math task values (9%), learning goals (5%), work avoidance (7%), and hope for success (6%) did not differ significantly from each other. Students’ fear of failure in math explained the smallest amount of unique variance in their math grades (4%) but the relative weight of students’ fear of failure did not differ significantly from that of students’ hope for success, work avoidance, and learning goals. The relative weights of students’ performance-avoidance goals were not significant in Model 3.

Turning to German grades: In Model 3, students’ prior grade in German was the strongest predictor (64%), followed by German self-concept (10%). Students’ fear of failure in German (6%), their verbal intelligence (4%), task values (4%), learning goals (4%), and hope for success (4%) explained less variance in German grades and did not differ significantly from each other but were significantly different from zero ( p < 0.05). The relative weights of students’ performance goals and work avoidance were not significant in Model 3.

In the present studies, we aimed to investigate the relative importance of several achievement motivation constructs in predicting students’ academic achievement. We sought to overcome the limitations of previous research in this field by (1) considering several theoretically and empirically distinct motivational constructs, (2) students’ intelligence, and their prior achievement, and (3) by assessing all predictors at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. We applied sophisticated statistical procedures to investigate the relations in three different domains, namely school in general, math, and German.

Relative Importance of Achievement Motivation Constructs for Academic Achievement

Out of the motivational predictor variables, students’ ability self-concepts explained the largest amount of variance in their academic achievement across all sets of analyses and across all investigated domains. Even when intelligence and prior grades were controlled for, students’ ability self-concepts accounted for at least 10% of the variance in the criterion. The relative superiority of ability self-perceptions is in line with the available literature on this topic (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ) and with numerous studies that have investigated the relations between students’ self-concept and their achievement (e.g., Möller et al., 2009 ; Huang, 2011 ). Ability self-concepts showed even higher relative weights than the corresponding intelligence scores. Whereas some previous studies have suggested that self-concepts and intelligence are at least equally important when predicting students’ grades (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Weber et al., 2013 ; Schneider et al., 2018 ), our findings indicate that it might be even more important to believe in own school-related abilities than to possess outstanding cognitive capacities to achieve good grades (see also Lotz et al., 2018 ). Such a conclusion was supported by the fact that we examined the relative importance of all predictor variables across three domains and at the same levels of specificity, thus maximizing criterion-related validity (see Baranik et al., 2010 ). This procedure represents a particular strength of our study and sets it apart from previous studies in the field (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). Alternatively, our findings could be attributed to the sample we investigated at least to some degree. The students examined in the present study were selected for the academic track in Germany, and this makes them rather homogeneous in their cognitive abilities. It is therefore plausible to assume that the restricted variance in intelligence scores decreased the respective criterion validities.

When all variables were assessed at the same level of specificity, the achievement motives hope for success and fear of failure were the second and third best motivational predictors of academic achievement and more important than in the study by Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) . This result underlines the original conceptualization of achievement motives as broad personal tendencies that energize approach or avoidance behavior across different contexts and situations ( Elliot, 2006 ). However, the explanatory power of achievement motives was higher in the more specific domains of math and German, thereby also supporting the suggestion made by Sparfeldt and Rost (2011) to conceptualize achievement motives more domain-specifically. Conceptually, achievement motives and ability self-concepts are closely related. Individuals who believe in their ability to succeed often show greater hope for success than fear of failure and vice versa ( Brunstein and Heckhausen, 2008 ). It is thus not surprising that the two constructs showed similar stability in their relative effects on academic achievement across the three investigated domains. Concerning the specific mechanisms through which students’ achievement motives and ability self-concepts affect their achievement, it seems that they elicit positive or negative valences in students, and these valences in turn serve as simple but meaningful triggers of (un)successful school-related behavior. The large and consistent effects for students’ ability self-concept and their hope for success in our study support recommendations from positive psychology that individuals think positively about the future and regularly provide affirmation to themselves by reminding themselves of their positive attributes ( Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). Future studies could investigate mediation processes. Theoretically, it would make sense that achievement motives defined as broad personal tendencies affect academic achievement via expectancy beliefs like ability self-concepts (e.g., expectancy-value theory by Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ; see also, Atkinson, 1957 ).

Although task values and learning goals did not contribute much toward explaining the variance in GPA, these two constructs became even more important for explaining variance in math and German grades. As Elliot (2006) pointed out in his hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation, achievement motives serve as basic motivational principles that energize behavior. However, they do not guide the precise direction of the energized behavior. Instead, goals and task values are commonly recruited to strategically guide this basic motivation toward concrete aims that address the underlying desire or concern. Our results are consistent with Elliot’s (2006) suggestions. Whereas basic achievement motives are equally important at abstract and specific achievement levels, task values and learning goals release their full explanatory power with increasing context-specificity as they affect students’ concrete actions in a given school subject. At this level of abstraction, task values and learning goals compete with more extrinsic forms of motivation, such as performance goals. Contrary to several studies in achievement-goal research, we did not demonstrate the importance of either performance-approach or performance-avoidance goals for academic achievement.

Whereas students’ ability self-concept showed a high relative importance above and beyond intelligence, with few exceptions, each of the remaining motivation constructs explained less than 5% of the variance in students’ academic achievement in the full model including intelligence measures. One might argue that the high relative importance of students’ ability self-concept is not surprising because students’ ability self-concepts more strongly depend on prior grades than the other motivation constructs. Prior grades represent performance feedback and enable achievement comparisons that are seen as the main determinants of students’ ability self-concepts (see Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2002 ). However, we included students’ prior grades in the analyses and students’ ability self-concepts still were the most powerful predictors of academic achievement out of the achievement motivation constructs that were considered. It is thus reasonable to conclude that the high relative importance of students’ subjective beliefs about their abilities is not only due to the overlap of this believes with prior achievement.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Our study confirms and extends the extant work on the power of students’ ability self-concept net of other important motivation variables even when important methodological aspects are considered. Strength of the study is the simultaneous investigation of different achievement motivation constructs in different academic domains. Nevertheless, we restricted the range of motivation constructs to ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives. It might be interesting to replicate the findings with other motivation constructs such as academic self-efficacy ( Pajares, 2003 ), individual interest ( Renninger and Hidi, 2011 ), or autonomous versus controlled forms of motivation ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ). However, these constructs are conceptually and/or empirically very closely related to the motivation constructs we considered (e.g., Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ; Marsh et al., 2018 ). Thus, it might well be the case that we would find very similar results for self-efficacy instead of ability self-concept as one example.

A second limitation is that we only focused on linear relations between motivation and achievement using a variable-centered approach. Studies that considered different motivation constructs and used person-centered approaches revealed that motivation factors interact with each other and that there are different profiles of motivation that are differently related to students’ achievement (e.g., Conley, 2012 ; Schwinger et al., 2016 ). An important avenue for future studies on students’ motivation is to further investigate these interactions in different academic domains.

Another limitation that might suggest a potential avenue for future research is the fact that we used only grades as an indicator of academic achievement. Although, grades are of high practical relevance for the students, they do not necessarily indicate how much students have learned, how much they know and how creative they are in the respective domain (e.g., Walton and Spencer, 2009 ). Moreover, there is empirical evidence that the prediction of academic achievement differs according to the particular criterion that is chosen (e.g., Lotz et al., 2018 ). Using standardized test performance instead of grades might lead to different results.

Our study is also limited to 11th and 12th graders attending the highest academic track in Germany. More balanced samples are needed to generalize the findings. A recent study ( Ben-Eliyahu, 2019 ) that investigated the relations between different motivational constructs (i.e., goal orientations, expectancies, and task values) and self-regulated learning in university students revealed higher relations for gifted students than for typical students. This finding indicates that relations between different aspects of motivation might differ between academically selected samples and unselected samples.

Finally, despite the advantages of relative weight analyses, this procedure also has some shortcomings. Most important, it is based on manifest variables. Thus, differences in criterion validity might be due in part to differences in measurement error. However, we are not aware of a latent procedure that is comparable to relative weight analyses. It might be one goal for methodological research to overcome this shortcoming.

We conducted the present research to identify how different aspects of students’ motivation uniquely contribute to differences in students’ achievement. Our study demonstrated the relative importance of students’ ability self-concepts, their task values, learning goals, and achievement motives for students’ grades in different academic subjects above and beyond intelligence and prior achievement. Findings thus broaden our knowledge on the role of students’ motivation for academic achievement. Students’ ability self-concept turned out to be the most important motivational predictor of students’ grades above and beyond differences in their intelligence and prior grades, even when all predictors were assessed domain-specifically. Out of two students with similar intelligence scores, same prior achievement, and similar task values, goals and achievement motives in a domain, the student with a higher domain-specific ability self-concept will receive better school grades in the respective domain. Therefore, there is strong evidence that believing in own competencies is advantageous with respect to academic achievement. This finding shows once again that it is a promising approach to implement validated interventions aiming at enhancing students’ domain-specific ability-beliefs in school (see also Muenks et al., 2017 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ).

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

In Germany, institutional approval was not required by default at the time the study was conducted. That is, why we cannot provide a formal approval by the institutional ethics committee. We verify that the study is in accordance with established ethical guidelines. Participation was voluntarily and no deception took place. Before testing, we received informed consent forms from the parents of the students who were under the age of 18 on the day of the testing. If students did not want to participate, they could spend the testing time in their teacher’s room with an extra assignment. All students agreed to participate. We included this information also in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

RS conceived and supervised the study, curated the data, performed the formal analysis, investigated the results, developed the methodology, administered the project, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. AW wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. MS performed the formal analysis, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. BS conceived the study, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

We acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Technische Universität Dortmund/TU Dortmund University within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude–behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84, 888–918. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amthauer, R., Brocke, B., Liepmann, D., and Beauducel, A. (2001). Intelligenz-Struktur-Test 2000 R [Intelligence-Structure-Test 2000 R] . Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Google Scholar

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 64, 359–372. doi: 10.1037/h0043445

Baranik, L. E., Barron, K. E., and Finney, S. J. (2010). Examining specific versus general measures of achievement goals. Hum. Perform. 23, 155–172. doi: 10.1080/08959281003622180

Ben-Eliyahu, A. (2019). A situated perspective on self-regulated learning from a person-by-context perspective. High Ability Studies . doi: 10.1080/13598139.2019.1568828

Brunstein, J. C., and Heckhausen, H. (2008). Achievement motivation. in Motivation and Action eds J. Heckhausen and H. Heckhausen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 137–183.

Conley, A. M. (2012). Patterns of motivation beliefs: combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 32–47. doi: 10.1037/a0026042

Dweck, C. S., and Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95, 256–273. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., and Kaczala, C. M., and Meece, J. L. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. in Achievement and Achievement Motivation ed J. T. Spence. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, 75–146

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: the structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 215–225. doi: 10.1177/0146167295213003

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R. D., and Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Dev. 64, 830–847. doi: 10.2307/1131221

Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motiv. Emot. 30, 111–116. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7

Elliot, A. J., and Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 218–232. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218

Elliot, A. J., and McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 x 2 achievement goal framework. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80, 501–519. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.80.3.501

Gjesme, T., and Nygard, R. (1970). Achievement-Related Motives: Theoretical Considerations and Construction of a Measuring Instrument . Olso: University of Oslo.

Göttert, R., and Kuhl, J. (1980). AMS — achievement motives scale von gjesme und nygard - deutsche fassung [AMS — German version]. in Motivationsförderung im Schulalltag [Enhancement of Motivation in the School Context] eds F. Rheinberg, and S. Krug, Göttingen: Hogrefe, 194–200

Hailikari, T., Nevgi, A., and Komulainen, E. (2007). Academic self-beliefs and prior knowledge as predictors of student achievement in mathematics: a structural model. Educ. Psychol. 28, 59–71. doi: 10.1080/01443410701413753

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Carter, S. M., Lehto, A. T., and Elliot, A. J. (1997). Predictors and consequences of achievement goals in the college classroom: maintaining interest and making the grade. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 1284–1295. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1284

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of 800+ Meta-Analyses on Achievement . Oxford: Routledge.

Huang, C. (2011). Self-concept and academic achievement: a meta-analysis of longitudinal relations. J. School Psychol. 49, 505–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hulleman, C. S., Schrager, S. M., Bodmann, S. M., and Harackiewicz, J. M. (2010). A meta-analytic review of achievement goal measures: different labels for the same constructs or different constructs with similar labels? Psychol. Bull. 136, 422–449. doi: 10.1037/a0018947

Johnson, J. W. (2004). Factors affecting relative weights: the influence of sampling and measurement error. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 283–299. doi: 10.1177/1094428104266018

Johnson, J. W., and LeBreton, J. M. (2004). History and use of relative importance indices in organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 238–257. doi: 10.1177/1094428104266510

Kriegbaum, K., Jansen, M., and Spinath, B. (2015). Motivation: a predictor of PISA’s mathematical competence beyond intelligence and prior test achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 43, 140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.026

Kumar, S., and Jagacinski, C. M. (2011). Confronting task difficulty in ego involvement: change in performance goals. J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 664–682. doi: 10.1037/a0023336

Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., and Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: can one construct predict them all? J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 86, 148–161. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.148

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Wormington, S. V., Snyder, K. E., Riggsbee, J., Perez, T., Ben-Eliyahu, A., et al. (2018). Multiple pathways to success: an examination of integrative motivational profiles among upper elementary and college students. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 1026–1048 doi: 10.1037/edu0000245

Lotz, C., Schneider, R., and Sparfeldt, J. R. (2018). Differential relevance of intelligence and motivation for grades and competence tests in mathematics. Learn. Individ. Differ. 65, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.03.005

Marsh, H. W. (1990). Causal ordering of academic self-concept and academic achievement: a multiwave, longitudinal panel analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 646–656. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.646

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., et al. (2018). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. J. Educ. Psychol. 111, 331–353. doi: 10.1037/edu0000281

Marsh, H. W., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Köller, O., and Baumert, J. (2005). Academic self-concept, interest, grades and standardized test scores: reciprocal effects models of causal ordering. Child Dev. 76, 397–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00853.x

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J., Clark, R., and Lowell, E. (1953). The Achievement Motive . New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Middleton, M. J., and Midgley, C. (1997). Avoiding the demonstration of lack of ability: an underexplored aspect of goal theory. Journal J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 710–718. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.710

Möller, J., Pohlmann, B., Köller, O., and Marsh, H. W. (2009). A meta-analytic path analysis of the internal/external frame of reference model of academic achievement and academic self-concept. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 1129–1167. doi: 10.3102/0034654309337522

Muenks, K., Wigfield, A., Yang, J. S., and O’Neal, C. (2017). How true is grit? Assessing its relations to high school and college students’ personality characteristics, self-regulation, engagement, and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 599–620. doi: 10.1037/edu0000153.

Muenks, K., Yang, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2018). Associations between grit, motivation, and achievement in high school students. Motiv. Sci. 4, 158–176. doi: 10.1037/mot0000076

Murphy, P. K., and Alexander, P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 3–53. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychol. Rev. 91, 328–346. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: a review of the literature. Read. Writ. Q. 19, 139–158. doi: 10.1080/10573560308222

Pintrich, P. R., Marx, R. W., and Boyle, R. A. (1993). Beyond cold conceptual change: the role of motivational beliefs and classroom contextual factors in the process of conceptual change. Rev. Educ. Res. 63, 167–199. doi: 10.3102/00346543063002167

Plante, I., O’Keefe, P. A., and Théorêt, M. (2013). The relation between achievement goal and expectancy-value theories in predicting achievement-related outcomes: a test of four theoretical conceptions. Motiv. Emot. 37, 65–78. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9282-9

Renninger, K. A., and Hidi, S. (2011). Revisiting the conceptualization, measurement, and generation of interest. Educ. Psychol. 46, 168–184. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.587723

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., and Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 130, 261–288. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Schneider, R., Lotz, C., and Sparfeldt, J. R. (2018). Smart, confident, and interested: contributions of intelligence, self-concepts, and interest to elementary school achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 62, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.01.003

Schöne, C., Dickhäuser, O., Spinath, B., and Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2002). Die Skalen zur Erfassung des schulischen Selbstkonzepts (SESSKO) [Scales for Measuring the Academic Ability Self-Concept] . Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Schwinger, M., Steinmayr, R., and Spinath, B. (2016). Achievement goal profiles in elementary school: antecedents, consequences, and longitudinal trajectories. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 46, 164–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.006

Seligman, M. E., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2002). Internal and external frames of reference for academic self-concept. Educ. Psychol. 37, 233–244. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3704_3

Sparfeldt, J. R., Buch, S. R., Wirthwein, L., and Rost, D. H. (2007). Zielorientierungen: Zur Relevanz der Schulfächer. [Goal orientations: the relevance of specific goal orientations as well as specific school subjects]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie , 39, 165–176. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637.39.4.165

Sparfeldt, J. R., and Rost, D. H. (2011). Content-specific achievement motives. Person. Individ. Differ. 50, 496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.016

Spinath, B., Spinath, F. M., Harlaar, N., and Plomin, R. (2006). Predicting school achievement from general cognitive ability, self-perceived ability, and intrinsic value. Intelligence 34, 363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2005.11.004

Spinath, B., and Steinmayr, R. (2012). The roles of competence beliefs and goal orientations for change in intrinsic motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 1135–1148. doi: 10.1037/a0028115

Spinath, B., Stiensmeier-Pelster, J., Schöne, C., and Dickhäuser, O. (2002). Die Skalen zur Erfassung von Lern- und Leistungsmotivation (SELLMO)[Measurement scales for learning and performance motivation] . Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Steinmayr, R., and Amelang, M. (2006). First results regarding the criterion validity of the I-S-T 2000 R concerning adults of both sex. Diagnostica 52, 181–188.

Steinmayr, R., and Spinath, B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 19, 80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2008.05.004

Steinmayr, R., and Spinath, B. (2010). Konstruktion und Validierung einer Skala zur Erfassung subjektiver schulischer Werte (SESSW) [construction and validation of a scale for the assessment of school-related values]. Diagnostica 56, 195–211. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924/a000023

Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., and Wigfield, A. (2018). Does students’ grit predict their school achievement above and beyond their personality, motivation, and engagement? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 53, 106–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.004

Tonidandel, S., and LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3

Walton, G. M., and Spencer, S. J. (2009). Latent ability grades and test scores systematically underestimate the intellectual ability of negatively stereotyped students. Psychol. Sci. 20, 1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02417.x

Weber, H. S., Lu, L., Shi, J., and Spinath, F. M. (2013). The roles of cognitive and motivational predictors in explaining school achievement in elementary school. Learn. Individ. Differ. 25, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.03.008

Weiner, B. (1992). Human Motivation: Metaphors, Theories, and Research . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Wigfield, A., and Cambria, J. (2010). Students’ achievement values, goal orientations, and interest: definitions, development, and relations to achievement outcomes. Dev. Rev. 30, 1–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2009.12.001

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A., Freedman-Doan, C., et al. (1997). Changes in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: a three-year study. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 451–469. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451

Wigfield, A., Tonks, S., and Klauda, S. L. (2016). “Expectancy-value theory,” in Handbook of Motivation in School , 2nd Edn. eds K. R. Wentzel and D. B. Mielecpesnm (New York, NY: Routledge), 55–74.

Keywords : academic achievement, ability self-concept, task values, goals, achievement motives, intelligence, relative weight analysis

Citation: Steinmayr R, Weidinger AF, Schwinger M and Spinath B (2019) The Importance of Students’ Motivation for Their Academic Achievement – Replicating and Extending Previous Findings. Front. Psychol. 10:1730. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01730

Received: 05 April 2019; Accepted: 11 July 2019; Published: 31 July 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Steinmayr, Weidinger, Schwinger and Spinath. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ricarda Steinmayr, cmljYXJkYS5zdGVpbm1heXJAdHUtZG9ydG11bmQuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Achievement Motivation

Achievement motivation definition.

The term achievement motivation may be defined by independently considering the words achievement and motivation. Achievement refers to competence (a condition or quality of effectiveness, ability, sufficiency, or success). Motivation refers to the energization (instigation) and direction (aim) of behavior. Thus, achievement motivation may be defined as the energization and direction of competence-relevant behavior or why and how people strive toward competence (success) and away from incompetence (failure).

The task of achievement motivation researchers is to explain and predict any and all behavior that involves the concept of competence. Importantly, their task is not to explain and predict any and all behavior that takes place in achievement situations. Much behavior that takes place in achievement situations has little or nothing to do with competence; limiting the achievement motivation literature to behavior involving competence is necessary for the literature to have coherence and structure. That being said, competence concerns and strivings are ubiquitous in daily life and are present in many situations not typically considered achievement situations. Examples include the following: a recreational gardener striving to grow the perfect orchid, a teenager seeking to become a better conversationalist, a politician working to become the most powerful leader in her state, and an elderly person concerned about losing his or her skills and abilities. Thus, the study of achievement motivation is quite a broad endeavor.

Many different achievement motivation variables have been studied over the years. Prominent among these variables are the following: achievement aspirations (the performance level one desires to reach or avoid not reaching; see research by Kurt Lewin, Ferdinand Hoppe), achievement needs/motives (general, emotion-based dispositions toward success and failure; see research by David McClelland, John Atkinson), test anxiety (worry and nervousness about the possibility of poor performance; see research by Charles Spielberger, Martin Covington), achievement attributions (beliefs about the cause of success and failure; see research by Bernard Weiner, Heinz Heckhausen), achievement goals (representations of success or failure outcomes that people strive to attain or avoid; see research by Carol Dweck, John Nicholls), implicit theories of ability (beliefs about the nature of competence and ability; see research by Carol Dweck, Robert Sternberg), perceived competence (beliefs about what one can and cannot accomplish; see research by Albert Bandura; Susan Harter), and competence valuation (importance judgments regarding the attainment of success or the avoidance of failure; see research by Jacqueline Eccles, Judy Harackiewicz). Achievement motivation researchers seek to determine both the antecedents and consequences of these different variables.

Many achievement motivation researchers focus on one of the aforementioned variables in their work, but others strive to integrate two or more of these constructs into an overarching conceptual framework. One such model that has received significant research attention of late is the hierarchical model of approach-avoidance achievement motivation (see research by Andrew Elliot and colleagues); this model is described in the following paragraphs.

Achievement goals are the centerpiece of the model, and these goals are differentiated according to two basic aspects of competence: how it is defined and how it is valenced. Competence is defined by the standard used to evaluate it, and three such standards are identified: an absolute (i.e., task-inherent) standard, an intrapersonal (i.e., the individual’s past attainment or maximum possible attainment) standard, and an interpersonal (i.e., normative) standard. At present, absolute and intraper-sonal standards are collapsed together within a “mastery goal” category, and normative standards are placed within a “performance goal” category. Competence is valenced by whether it is focused on a positive possibility that one would like to approach (success) or a negative possibility that one would like to avoid (failure).

Putting the definition and valence aspects of competence together yields four basic achievement goals that are presumed to comprehensively cover the range of competence-based strivings. Mastery-approach goals represent striving to approach absolute or intrapersonal competence, for example, striving to improve one’s performance. Mastery-avoidance goals represent striving to avoid absolute or intrapersonal incompetence, for example, striving not to do worse than one has done previously. Performance-approach goals represent striving to approach interpersonal competence, for example, striving to do better than others. Performance-avoidance goals represent striving to avoid interpersonal incompetence, for example, striving to avoid doing worse than others.

These achievement goals are posited to have an important and direct impact on the way people engage in achievement activities and, accordingly, the outcomes they incur. Broadly stated, mastery-approach and performance-approach goals are predicted to lead to adaptive behavior and different types of positive outcomes (e.g., mastery-approach goals are thought to optimally facilitate creativity and continuing interest, and performance-approach goals are thought to optimally facilitate performance attainment). Mastery-avoidance and, especially, performance-avoidance goals, on the other hand, are predicted to lead to maladaptive behavior and negative outcomes such as selecting easy instead of optimally challenging tasks, quitting when difficulty or failure is encountered, and performing poorly. A substantial amount of research over the past decade has supported these predictions.

Achievement goals are viewed as concrete, situation-specific variables that explain the specific aim or direction of people’s competence pursuits. Other variables are needed to explain why people orient toward different definitions and valences of competence in the first place, and why they adopt particular types of achievement goals. Higher-order variables such as achievement needs/motives, implicit theories of ability, general competence perceptions, and features of the achievement environment (e.g., norm-based vs. task-based performance evaluation, harsh vs. lenient performance evaluation) are used to explain achievement goal adoption. These variables are not posited to have a direct influence on achievement outcomes, but they are expected to have an indirect influence by prompting achievement goals that, in turn, exert a direct influence on achievement outcomes.

Achievement needs/motives may be used as an illustrative example. Two types of achievement needs/motives have been identified: the need for achievement, which is the dispositional tendency to experience pride upon success, and fear of failure, which is the dispositional tendency to experience shame upon failure. The need for achievement is predicted to lead to mastery-approach and performance-approach goals, whereas fear of failure is predicted to lead to mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals. Fear of failure is also predicted to lead to performance-approach goals, a need/motive to goal combination that represents an active striving toward success to avoid failure (i.e., active avoidance). The need for achievement and fear of failure are posited to have an indirect influence on achievement outcomes through their impact on achievement goal adoption. A number of empirical studies have provided evidence in support of these predictions, as well as many other hierarchically based predictions (involving other higher-order variables) derived from the model.

Models of achievement motivation are of theoretical importance because they help to explain and predict competence-relevant behavior in a systematic and generative fashion. Such models are also of practical importance because they highlight how factors besides intelligence and ability have a substantial impact on achievement outcomes. Competence is widely considered a basic need that all individuals require on a regular basis for psychological and physical well-being to accrue. The bad news from the achievement motivation literature is that many people exhibit motivation in achievement situations that leads to maladaptive behavior, undesirable achievement outcomes, and, ultimately, ill-being. The good news from the achievement motivation literature is that motivation is amenable to change.

References:

- Covington, M. V. (1992). Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Elliot, A. J., & Dweck, C. S. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford Press.

- Heckhausen, H., Schmalt, H.-D., & Schneider, K. (1985). Achievement motivation in perspective (M. Woodruff & R. Wicklund, Trans.). New York: Academic Press.

- McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

The Psychology of Motivation and Academic Achievement

The psychology of motivation and its impact on academic achievement is a complex and fascinating field. It delves into the internal and external factors that drive students to engage in learning, persist in the face of challenges, and ultimately succeed in their academic pursuits. This essay explores the role of motivation in academic achievement, the influence of self-efficacy and goal setting on performance, the impact of the learning environment, and the importance of understanding motivation for educators.

<h2 style="font-weight: bold; margin: 12px 0;">What is the role of motivation in academic achievement?</h2>Motivation plays a crucial role in academic achievement. It is the driving force that encourages students to engage in learning activities. Motivation can be intrinsic, coming from within the student and involving interest, enjoyment, and a desire for personal growth. Alternatively, it can be extrinsic, driven by external rewards or punishments. Both types of motivation can influence a student's willingness to learn and their overall academic performance. Intrinsic motivation often leads to deeper understanding and long-term knowledge retention, while extrinsic motivation can be effective in encouraging effort and persistence in the short term. However, a balance of both is often necessary for sustained academic achievement.

<h2 style="font-weight: bold; margin: 12px 0;">How does self-efficacy influence academic performance?</h2>Self-efficacy, or a student's belief in their ability to succeed, significantly influences academic performance. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to set challenging goals, persist in the face of difficulty, and use effective problem-solving strategies. They are also more resilient in the face of failure, viewing it as an opportunity to learn rather than a reflection of their abilities. This positive mindset can lead to improved academic performance and higher levels of achievement. On the other hand, students with low self-efficacy may avoid challenging tasks, give up easily, and experience stress and anxiety, which can hinder academic performance.

<h2 style="font-weight: bold; margin: 12px 0;">What is the impact of goal setting on student achievement?</h2>Goal setting is a powerful tool for enhancing student achievement. When students set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals, they have a clear direction and purpose for their learning. This process can increase motivation, as students can see the progress they are making towards their goals. It also encourages self-regulation, as students must monitor their progress, adjust their strategies, and manage their time and resources effectively. Research has shown that students who set and pursue their own learning goals tend to achieve higher academic outcomes than those who do not.

<h2 style="font-weight: bold; margin: 12px 0;">How does the learning environment affect student motivation and achievement?</h2>The learning environment can significantly impact student motivation and achievement. A supportive, inclusive, and engaging environment can foster intrinsic motivation and promote active learning. This includes providing challenging and relevant tasks, offering choice and autonomy, giving constructive feedback, and promoting a growth mindset. A positive relationship with teachers and peers can also enhance motivation by creating a sense of belonging and value. Conversely, a negative learning environment can undermine motivation and hinder academic achievement.

<h2 style="font-weight: bold; margin: 12px 0;">Why is understanding the psychology of motivation important for educators?</h2>Understanding the psychology of motivation is crucial for educators as it can inform effective teaching strategies and interventions. By understanding what motivates students, educators can tailor their instruction to meet students' needs and interests, thereby enhancing engagement and learning. They can also foster a growth mindset, promote self-efficacy, and facilitate goal setting, all of which can boost motivation and academic achievement. Furthermore, understanding motivation can help educators identify and support students who may be struggling with motivation, thereby preventing potential learning difficulties and promoting equity in education.

In conclusion, motivation is a powerful force that can significantly influence academic achievement. It is shaped by various factors, including self-efficacy, goal setting, and the learning environment. Understanding the psychology of motivation can equip educators with the knowledge and tools to foster a learning environment that enhances motivation, promotes academic achievement, and supports the holistic development of students. As such, it is a critical area of focus in the field of education.

Related Essays

Exploring the role of technology in modern accounting practices.

The accounting profession, once characterized by manual ledgers and laborious calculations, is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the relentless advancement of technology. This evolution is reshaping traditional practices, introducing new opportunities, and redefining the role of accountants in the modern business landscape. The Rise of Cloud-Based Accounting SoftwareCloud-based accounting software has emerged as a game-changer in modern accounting practices. These platforms offer numerous benefits, including real-time data access, automated tasks, and enhanced collaboration. With data stored securely in the cloud, accountants can access information from anywhere with an internet connection, eliminating the need for physical presence in the office. This accessibility streamlines workflows, improves efficiency, and enables accountants to provide timely financial insights to clients or stakeholders. Automation: Streamlining Repetitive TasksOne of the most significant impacts of technology on modern accounting practices is the automation of repetitive and time-consuming tasks. Software programs can now handle data entry, invoice processing, bank reconciliations, and other routine activities with speed and accuracy. This automation frees up accountants from mundane tasks, allowing them to focus on more strategic and analytical aspects of their roles, such as financial planning, risk management, and advisory services. Data Analytics: Unveiling Insights for Decision-MakingTechnology has ushered in the era of data analytics, empowering modern accounting practices with unprecedented insights. By leveraging data visualization tools, predictive modeling, and other analytical techniques, accountants can extract valuable information from vast datasets. These insights can be used to identify trends, forecast future performance, assess risks, and make informed business decisions. Data analytics enables accountants to move beyond traditional number-crunching and become strategic advisors to businesses. Blockchain Technology: Enhancing Transparency and SecurityBlockchain technology, renowned for its security and transparency, is also making its mark on modern accounting practices. By creating an immutable and distributed ledger, blockchain can revolutionize record-keeping, audit trails, and financial reporting. Smart contracts, self-executing agreements encoded on the blockchain, have the potential to automate contracts, reduce disputes, and enhance trust in financial transactions. The Evolving Role of the Modern AccountantAs technology continues to reshape the accounting landscape, the role of the modern accountant is evolving. While technical skills remain essential, there is a growing demand for professionals who possess a blend of technological proficiency, analytical capabilities, and business acumen. Accountants are now expected to be strategic advisors, data analysts, and technology enthusiasts who can leverage innovation to drive business growth and success.The integration of technology into modern accounting practices has brought about significant changes, transforming the way accountants work and interact with financial information. From cloud-based software to data analytics and blockchain technology, these advancements have streamlined processes, enhanced efficiency, and empowered accountants to provide greater value to businesses. As technology continues to evolve, the accounting profession must adapt and embrace innovation to thrive in the ever-changing digital landscape.

The Importance of Critical Thinking in Financial Decision Making