Was the Russian Sleep Experiment Real?

An account describing the horrific results of a 'russian sleep experiment' from the late 1940s is a work of modern creepy fiction., david mikkelson, published aug. 27, 2013.

About this rating

A popular creepy online tale of a "Russian Sleep Experiment" (with the improbable title tag of "Orange Soda") involves Soviet researchers who kept five people awake for fifteen consecutive days through the use of an "experimental gas based stimulant" and opens as follows:

Russian researchers in the late 1940's kept five people awake for fifteen days using an experimental gas based stimulant. They were kept in a sealed environment to carefully monitor their oxygen intake so the gas didn't kill them, since it was toxic in high concentrations. This was before closed circuit cameras so they had only microphones and 5 inch thick glass porthole sized windows into the chamber to monitor them. The chamber was stocked with books, cots to sleep on but no bedding, running water and toilet, and enough dried food to last all five for over a month. [Remainder of article here .]

This account isn't a historical record of a genuine 1940s sleep deprivation research project gone awry, however. It's merely a bit of supernatural fiction that gained widespread currency on the Internet after appearing on Creepypasta (a site for "short stories designed to unnerve and shock the reader") in August 2010.

By David Mikkelson

David Mikkelson founded the site now known as snopes.com back in 1994.

Why the Horrors of the 'Russian Sleep Experiment' Probably Didn't Happen

This animation investigates the facts behind this pervasive urban myth.

Especially if you haven't been getting a lot of sleep lately, you might wonder just how long you can go on like that. Exactly how long could you stay awake without cracking as a result of sleep deprivation? Some people say there was an over-the-top experiment for that. Experts are quick to debunk it.

The Russian Sleep Experiment is a popular urban myth which began to circulate online in "creepypasta" forums (so-named for the ease with which you could copy-paste spooky content) in the early 2010s. But could this deeply unsettling legend have had some roots in fact?

The story goes that Soviet-era scientists created a stimulant which they believed would enable soldiers to not require sleep for up to 30 days. They decided to test their new gas on five prisoners, promising them their freedom upon completion of the experiment. They locked the five men in a hermetically sealed chamber and began pumping in the gas. Within a few days, the men were exhibiting the kind of paranoia and psychosis that is a typical symptom of sleep deprivation. But as time went on, they began to act even more strangely.

15 days into the experiment, when scientists could no longer see the men through the thick glass of the chamber, or hear them through the microphones, they filled the room with fresh air and unlocked it. There, they discovered that one of the men was dead, and the four surviving test subjects were all sporting horrendously violent injuries, some of which appeared to be self-inflicted.

Attempts to sedate the men were either unsuccessful, or led to their deaths the moment they lost consciousness. Finally, when one of the researchers asked what exactly these men had become, the last surviving test subject told him that they represented the potential for evil that exists in all human beings, which is usually contained by sleep, but had been unleashed by their constant wakefulness. Chilling stuff.

Is any of the Russian Sleep Experiment actually true?

According to a video from The Infographics Channel on YouTube, which provides animated summaries of events from history, current events and literature, the Russian sleep experiment almost certainly has its basis in fiction. For one thing, there's the fact that the story's sole original source seems to be a website dedicated to telling creepy (made-up) stories. But even the science doesn't hold up.

Experts are quick to refute this myth as well. There's no scientific ground proving that gas (or any other substance, for that matter) can keep a person awake for 30 days, says Po-Chang Hsu, MD , an internal medicine physician and medical content expert at SleepingOcean. “Some drugs and high caffeine dosages may grant a couple of days without shut-eye, but 30 is impossible,” he says.

Additionally, this experiment is unlikely because of the effect sleep deprivation has on the brain, Dr. Hsu says.

“Even after a few days, a person can start hallucinating, which would make it extremely hard for them to perform simple daily actions, let alone deal with military assignments that require extreme focus,” he says.

So how long can someone truly stay awake?

The current documented world record for staying awake is a bit longer than 11 days , which was achieved by Randy Gardner in 1963. Gardner experienced severe behavioral and cognitive changes during those 11 days (even though he wanted to prove that nothing bad would happen when a person doesn’t sleep), Dr. Hsu says. He also experienced mood swings, memory issues, severe difficulty focusing, paranoia and hallucinations.

While there is some truth to the claims that amphetamines have been used to keep soldiers alert in historical times of war, there is no scientific evidence of a gas existing that could keep anyone awake for 15 days. And studies have found that after just 48 hours without sleep, people tend to become slower, disoriented, prone to making mistakes, and ultimately less effective as a soldier.

“Since the brain can’t function properly after being sleep-deprived for 11 days, it’s safe to assume things would get much worse if one tries to stay awake longer,” he says. “Consequently, those soldiers would’ve been useless even if they miraculously managed not to sleep for 30 days.”

Still, whoever came up with the story of the Russian sleep experiment in the first place deserves points for their creative writing... if not for medical accuracy.

Health and Nutrition Tips

8 Reasons You're Not Hungry

Water Fasting Is Almost Always a Really Bad Idea

What If Processed Food Was Actually Good for You?

Symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder in Men

The Key Heart Tests You're Probably Not Getting

Can Supplements Boost Your Erections and Sex Life?

10 Reasons You Can’t Get an Erection

Here's Exactly How Much Protein You Need

40 Healthy Snacks That Are Great for Weight Loss

Okra Water Is Now a Thing, Apparently

What a 'Normal' Resting Heart Rate Should Be

Walk Your Way to Weight Loss

Fact Check: 'Russian Sleep Experiment' Was NOT Real Event

- Jan 25, 2022

- by: Lead Stories Staff

Was the "Russian Sleep Experiment" a real historical event? No, that's not true: The "experiment" is a product of the creepypasta genre -- which consists of user-generated, horror-related content that spreads easily online -- and is not based on a historical account.

The claim, which has appeared in various iterations online, reappeared in a Facebook post (archived here ) on February 1, 2020. The post included a black-and-white image of a human-like creature and opened:

The Russian Sleep Experiment purports to recount an experiment that took place at a test facility in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s. In a military-sanctioned scientific experiment, five political prisoners were kept in a sealed gas chamber, with a continually administered airborne stimulant for the purpose of keeping the subjects awake for 15 continuous days. The prisoners are falsely promised freedom if they complete the experiment.

The post went on to describe how the political prisoners gradually, then swiftly, spiraled into violence and self-mutilation. The subjects all eventually died.

This is what the post looked like on Facebook on January 25, 2022:

The story of the Russian Sleep Experiment has been debunked by numerous outlets, including Snopes . According to a video created by Creepypasta Wiki , the story seemed to have originated in 2009 on an online forum. The story then appeared on the Creepypasta Wiki website in 2010 and was posted by a user known as Orange Soda.

The picture used in the Facebook post is of a Spazm prop, a Halloween prop of a monstrous-looking human in a straitjacket. That image can be found in a popular YouTube video of a reading of the Russian Sleep Experiment here and in the screenshot of the video included below:

(Source: YouTube screenshot taken on Tue Jan 25 18:36:00 2022 UTC)

The story may have been inspired by the unethical experiments committed against human subjects during World War II, particularly those that took place in Nazi concentration camps . However, there is no legitimate record of the Russian Sleep Experiment.

Lead Stories is a fact checking website that is always looking for the latest false, misleading, deceptive or inaccurate stories, videos or images going viral on the internet. Spotted something? Let us know! .

Lead Stories is a:

- Verified signatory of the IFCN Code of Principles

- Verified EFCSN member

- Facebook Third-Party Fact-Checking Partner

WhatsApp Tipline

Have a tip or a question? Chat with our friendly robots on WhatsApp!

Add our number +1 (404) 655-4223 , follow this link or scan the image below with your phone:

@leadstories

Subscribe to our newsletter

Please select all the ways you would like to hear from Lead Stories LLC:

You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link in the footer of our emails. For information about our privacy practices, please visit our website.

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Fact Check: 'Pro-Vaccine' Surgeon Did NOT Die Of COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Heart Attack

Fact Check: Biden Did NOT Cut Short Christmas Visit To Delaware

Fact Check: 2024 Continuing Resolution Did NOT Include 40% Pay Raise For Congress

Fact Check: FAKE Video Shows Car-Sized Drone Or Flying Object In Las Vegas

Fact Check: Biden Administration Did NOT Spend $3 Billion For Just 93 Postal Delivery Electric Vehicles

Fact Check: Donald Trump's Plan To End Birthright Citizenship Does NOT Mean Four Of His Children Would Have Been Denied Citizenship

Fact Check: Photo Of Nancy Parker Does NOT Show Altoona McDonald's Employee Who Reported Sighting Of Luigi Mangione In Pennsylvania

Most recent.

Fact Check: Video Does NOT Show New Jersey Drone 'Spraying' -- It's Jetliner Contrail

Fact Check: Video Does NOT Show Weapon Fired At NJ Drone -- FAKE Gunfire Added To Original Clip

Fact Check: Samir El Hydeouchi NOT Identified As The Driver In Magdeburg Christmas Market Attack -- Sam Hyde Hoax

Fact Check: House Democrats NOT Only Ones To Vote Against Spending Bill

Fact Check: Elon Musk's Mother Did NOT Say 'The Poor Should Have Kids So My Son's Factories Have Workers' In December 2024

Share your opinion, lead stories.

Frankenstein: the real experiments that inspired the fictional science

Professor of History, Aberystwyth University

Disclosure statement

Iwan Morus receives funding from the AHRC as part of the Unsettling Scientific Stories project.

Aberystwyth University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

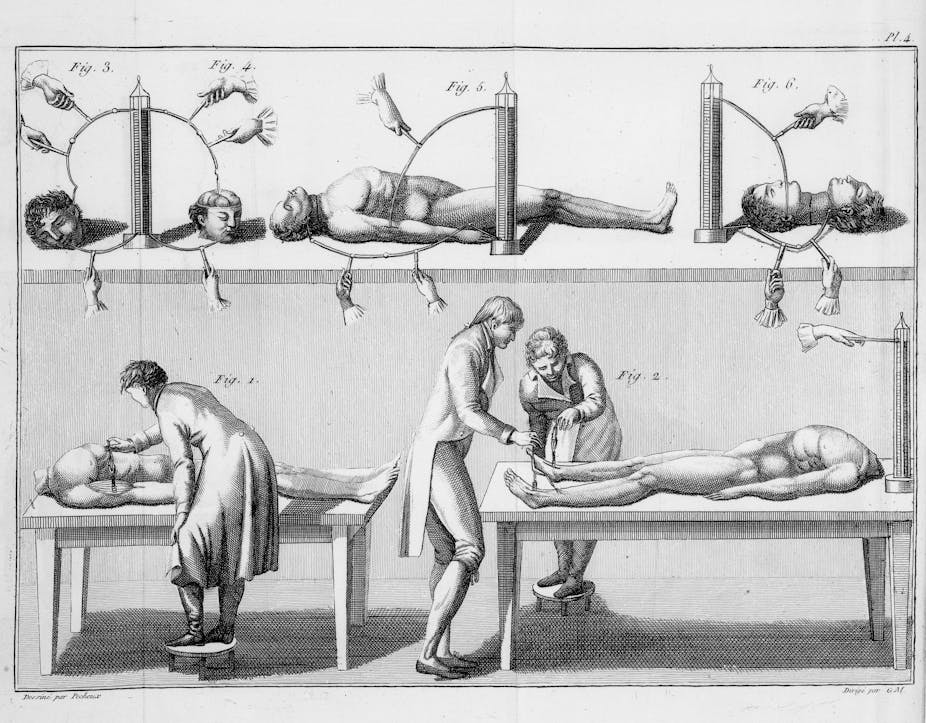

On January 17 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified.

The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “ animal electricity ” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Times newspaper reported:

On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.

It looked to some spectators “as if the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life.”

By the time Aldini was experimenting on Forster the idea that there was some peculiarly intimate relationship between electricity and the processes of life was at least a century old. Isaac Newton speculated along such lines in the early 1700s. In 1730, the English astronomer and dyer Stephen Gray demonstrated the principle of electrical conductivity. Gray suspended an orphan boy on silk cords in mid air , and placed a positively charged tube near the boy’s feet, creating a negative charge in them. Due to his electrical isolation, this created a positive charge in the child’s other extremities, causing a nearby dish of gold leaf to be attracted to his fingers.

In France in 1746 Jean Antoine Nollet entertained the court at Versailles by causing a company of 180 royal guardsmen to jump simultaneously when the charge from a Leyden jar (an electrical storage device) passed through their bodies.

It was to defend his uncle’s theories against the attacks of opponents such as Alessandro Volta that Aldini carried out his experiments on Forster. Volta claimed that “animal” electricity was produced by the contact of metals rather than being a property of living tissue, but there were several other natural philosophers who took up Galvani’s ideas with enthusiasm. Alexander von Humboldt experimented with batteries made entirely from animal tissue. Johannes Ritter even carried out electrical experiments on himself to explore how electricity affected the sensations.

The idea that electricity really was the stuff of life and that it might be used to bring back the dead was certainly a familiar one in the kinds of circles in which the young Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley – the author of Frankenstein – moved. The English poet, and family friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was fascinated by the connections between electricity and life. Writing to his friend the chemist Humphry Davy after hearing that he was giving lectures at the Royal Institution in London, he told him how his “motive muscles tingled and contracted at the news, as if you had bared them and were zincifying the life-mocking fibres”. Percy Bysshe Shelley himself – who would become Wollstonecraft’s husband in 1816 – was another enthusiast for galvanic experimentation .

Vital knowledge

Aldini’s experiments with the dead attracted considerable attention. Some commentators poked fun at the idea that electricity could restore life, laughing at the thought that Aldini could “ make dead people cut droll capers ”. Others took the idea very seriously. Lecturer Charles Wilkinson, who assisted Aldini in his experiments, argued that galvanism was “an energising principle, which forms the line of distinction between matter and spirit, constituting in the great chain of the creation, the intervening link between corporeal substance and the essence of vitality”.

In 1814 the English surgeon John Abernethy made much the same sort of claim in the annual Hunterian lecture at the Royal College of Surgeons. His lecture sparked a violent debate with fellow surgeon William Lawrence. Abernethy claimed that electricity was (or was like) the vital force while Lawrence denied that there was any need to invoke a vital force at all to explain the processes of life. Both Mary and Percy Shelley certainly knew about this debate – Lawrence was their doctor.

By the time Frankenstein was published in 1818, its readers would have been familiar with the notion that life could be created or restored with electricity. Just a few months after the book appeared, the Scottish chemist Andrew Ure carried out his own electrical experiments on the body of Matthew Clydesdale, who had been executed for murder. When the dead man was electrified , Ure wrote, “every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer’s face”.

Ure reported that the experiments were so gruesome that “several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment, and one gentleman fainted”. It is tempting to speculate about the degree to which Ure had Mary Shelley’s recent novel in mind as he carried out his experiments. His own account of them was certainly quite deliberately written to highlight their more lurid elements.

Frankenstein might look like fantasy to modern eyes, but to its author and original readers there was nothing fantastic about it. Just as everyone knows about artificial intelligence now, so Shelley’s readers knew about the possibilities of electrical life. And just as artificial intelligence (AI) invokes a range of responses and arguments now, so did the prospect of electrical life – and Shelley’s novel – then.

The science behind Frankenstein reminds us that current debates have a long history – and that in many ways the terms of our debates now are determined by it. It was during the 19th century that people started thinking about the future as a different country, made out of science and technology. Novels such as Frankenstein, in which authors made their future out of the ingredients of their present, were an important element in that new way of thinking about tomorrow.

Thinking about the science that made Frankenstein seem so real in 1818 might help us consider more carefully the ways we think now about the possibilities – and the dangers – of our present futures.

- Frankenstein

- Mary Shelley

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 195,500 academics and researchers from 5,104 institutions.

Register now

October 6, 2022

11 min read

The Universe Is Not Locally Real, and the Physics Nobel Prize Winners Proved It

Elegant experiments with entangled light have laid bare a profound mystery at the heart of reality

By Dan Garisto edited by Lee Billings

Athul Satheesh/500px/Getty Images

One of the more unsettling discoveries in the past half a century is that the universe is not locally real. In this context, “real” means that objects have definite properties independent of observation—an apple can be red even when no one is looking. “Local” means that objects can be influenced only by their surroundings and that any influence cannot travel faster than light. Investigations at the frontiers of quantum physics have found that these things cannot both be true. Instead the evidence shows that objects are not influenced solely by their surroundings, and they may also lack definite properties prior to measurement.

This is, of course, deeply contrary to our everyday experiences. As Albert Einstein once bemoaned to a friend, “Do you really believe the moon is not there when you are not looking at it?” To adapt a phrase from author Douglas Adams, the demise of local realism has made a lot of people very angry and has been widely regarded as a bad move.

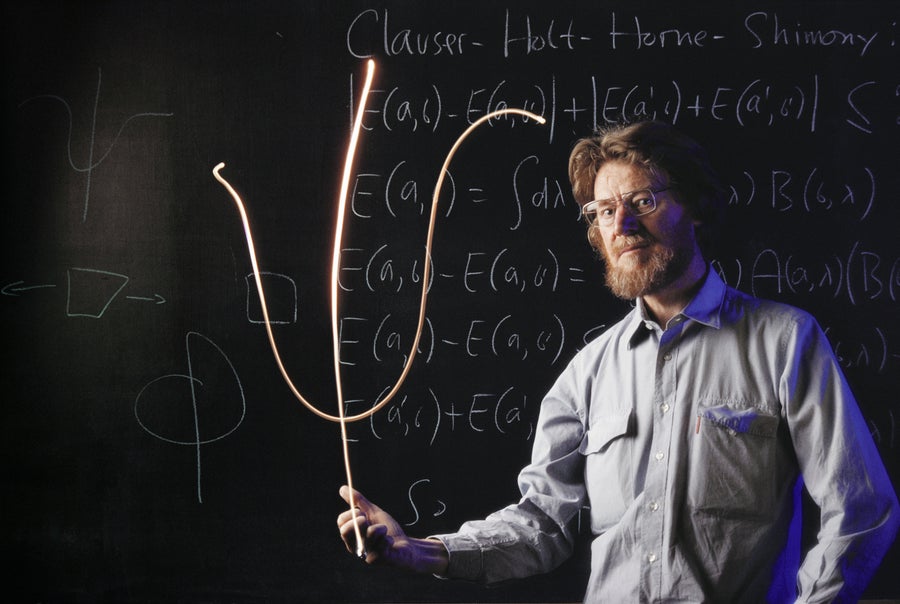

Blame for this achievement has been laid squarely on the shoulders of three physicists: John Clauser, Alain Aspect and Anton Zeilinger. They equally split the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science.” (“Bell inequalities” refers to the trailblazing work of physicist John Stewart Bell of Northern Ireland, who laid the foundations for the 2022 Physics Nobel in the early 1960s.) Colleagues agreed that the trio had it coming, deserving this reckoning for overthrowing reality as we know it. “It was long overdue,” says Sandu Popescu, a quantum physicist at the University of Bristol in England. “Without any doubt, the prize is well deserved.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The experiments beginning with the earliest one of Clauser and continuing along show that this stuff isn’t just philosophical, it’s real—and like other real things, potentially useful,” says Charles Bennett, an eminent quantum researcher at IBM. “Each year I thought, ‘Oh, maybe this is the year,’” says David Kaiser, a physicist and historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “[In 2022] it really was. It was very emotional—and very thrilling.”

The journey from fringe to favor was a long one. From about 1940 until as late as 1990, studies of so-called quantum foundations were often treated as philosophy at best and crackpottery at worst. Many scientific journals refused to publish papers on the topic, and academic positions indulging such investigations were nearly impossible to come by. In 1985 Popescu’s adviser warned him against a Ph.D. in the subject. “He said, ‘Look, if you do that, you will have fun for five years, and then you will be jobless,’” Popescu says.

Today quantum information science is among the most vibrant subfields in all of physics. It links Einstein’s general theory of relativity with quantum mechanics via the still mysterious behavior of black holes. It dictates the design and function of quantum sensors, which are increasingly being used to study everything from earthquakes to dark matter. And it clarifies the often confusing nature of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon that is pivotal to modern materials science and that lies at the heart of quantum computing. “What even makes a quantum computer ‘quantum?’” Nicole Yunger Halpern, a physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, asks rhetorically. “One of the most popular answers is entanglement, and the main reason why we understand entanglement is the grand work participated in by Bell and these Nobel Prize winners. Without that understanding of entanglement, we probably wouldn’t be able to realize quantum computers.”

Work by John Stewart Bell in the 1960s sparked a quiet revolution in quantum physics.

Peter Menzel/Science Source

FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS

The trouble with quantum mechanics was never that it made the wrong predictions—in fact, the theory described the microscopic world splendidly right from the start when physicists devised it in the opening decades of the 20th century. What Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen took issue with, as they explained in their iconic 1935 paper, was the theory’s uncomfortable implications for reality. Their analysis, known by their initials EPR, centered on a thought experiment meant to illustrate the absurdity of quantum mechanics. The goal was to show how under certain conditions the theory can break—or at least deliver nonsensical results that conflict with our deepest assumptions about reality.

A simplified and modernized version of EPR goes something like this: Pairs of particles are sent off in different directions from a common source, targeted for two observers, Alice and Bob, each stationed at opposite ends of the solar system. Quantum mechanics dictates that it is impossible to know the spin, a quantum property of individual particles, prior to measurement. Once Alice measures one of her particles, she finds its spin to be either “up” or “down.” Her results are random, and yet when she measures up, she instantly knows that Bob’s corresponding particle—which had a random, indefinite spin—must now be down. At first glance, this is not so odd. Maybe the particles are like a pair of socks—if Alice gets the right sock, Bob must have the left.

But under quantum mechanics, particles are not like socks, and only when measured do they settle on a spin of up or down. This is EPR’s key conundrum: If Alice’s particles lack a spin until measurement, then how (as they whiz past Neptune) do they know what Bob’s particles will do as they fly out of the solar system in the other direction? Each time Alice measures, she quizzes her particle on what Bob will get if he flips a coin: up or down? The odds of correctly predicting this even 200 times in a row are one in 10 60 —a number greater than all the atoms in the solar system. Yet despite the billions of kilometers that separate the particle pairs, quantum mechanics says Alice’s particles can keep correctly predicting, as though they were telepathically connected to Bob’s particles.

Designed to reveal the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, EPR eventually led to experimental results that instead reinforce the theory’s most mind-boggling tenets. Under quantum mechanics, nature is not locally real: particles may lack properties such as spin up or spin down prior to measurement, and they seem to talk to one another no matter the distance. (Because the outcomes of measurements are random, these correlations cannot be used for faster-than-light communication.)

Physicists skeptical of quantum mechanics proposed that this puzzle could be explained by hidden variables, factors that existed in some imperceptible level of reality, under the subatomic realm, that contained information about a particle’s future state. They hoped that in hidden variable theories, nature could recover the local realism denied it by quantum mechanics. “One would have thought that the arguments of Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen would produce a revolution at that moment, and everybody would have started working on hidden variables,” Popescu says.

Einstein’s “attack” on quantum mechanics, however, did not catch on among physicists, who by and large accepted quantum mechanics as is. This was less a thoughtful embrace of nonlocal reality than a desire not to think too hard—a head-in-the-sand sentiment later summarized by American physicist N. David Mermin as a demand to “shut up and calculate.” The lack of interest was driven in part because John von Neumann, a highly regarded scientist, had in 1932 published a mathematical proof ruling out hidden variable theories. Von Neumann’s proof, it must be said, was refuted just three years later by a young female mathematician, Grete Hermann, but at the time no one seemed to notice.

The problem of nonlocal realism would languish for another three decades before being shattered by Bell. From the start of his career, Bell was bothered by quantum orthodoxy and sympathetic toward hidden variable theories. Inspiration struck him in 1952, when he learned that American physicist David Bohm had formulated a viable nonlocal hidden variable interpretation of quantum mechanics—something von Neumann had claimed was impossible.

Bell mulled the ideas for years, as a side project to his job working as a particle physicist at CERN near Geneva. In 1964 he rediscovered the same flaws in von Neumann’s argument that Hermann had. And then, in a triumph of rigorous thinking, Bell concocted a theorem that dragged the question of local hidden variables from its metaphysical quagmire onto the concrete ground of experiment.

Typically local hidden variable theories and quantum mechanics predict indistinguishable experimental outcomes. What Bell realized is that under precise circumstances, an empirical discrepancy between the two can emerge. In the eponymous Bell test (an evolution of the EPR thought experiment), Alice and Bob receive the same paired particles, but now they each have two different detector settings—A and a, B and b. These detector settings are an additional trick to throw off Alice and Bob’s apparent telepathy. In local hidden variable theories, one particle cannot know which question the other is asked. Their correlation is secretly set ahead of time and is not sensitive to updated detector settings. But according to quantum mechanics, when Alice and Bob use the same settings (both uppercase or both lowercase), each particle is aware of the question the other is posed, and the two will correlate perfectly—in sync in a way no local theory can account for. They are, in a word, entangled.

Measuring the correlation multiple times for many particle pairs, therefore, could prove which theory was correct. If the correlation remained below a limit derived from Bell’s theorem, this would suggest hidden variables were real; if it exceeded Bell’s limit, then the mind-boggling tenets of quantum mechanics would reign supreme. And yet, in spite of its potential to help determine the nature of reality, Bell’s theorem languished unnoticed in a relatively obscure journal for years.

THE BELL TOLLS FOR THEE

In 1967 a graduate student at Columbia University named John Clauser accidentally stumbled across a library copy of Bell’s paper and became enthralled by the possibility of proving hidden variable theories correct. When Clauser wrote to Bell two years later, asking if anyone had performed the test, it was among the first feedback Bell had received.

Three years after that, with Bell’s encouragement, Clauser and his graduate student Stuart Freedman performed the first Bell test. Clauser had secured permission from his supervisors but little in the way of funds, so he became, as he said in a later interview, adept at “dumpster diving” to obtain equipment—some of which he and Freedman then duct-taped together. In Clauser’s setup—a kayak-size apparatus requiring careful tuning by hand—pairs of photons were sent in opposite directions toward detectors that could measure their state, or polarization.

Unfortunately for Clauser and his infatuation with hidden variables, once he and Freedman completed their analysis, they had to conclude that they had found strong evidence against them. Still, the result was hardly conclusive because of various “loopholes” in the experiment that conceivably could allow the influence of hidden variables to slip through undetected. The most concerning of these was the locality loophole: if either the photon source or the detectors could have somehow shared information (which was plausible within an object the size of a kayak), the resulting measured correlations could still emerge from hidden variables. As M.I.T.’s Kaiser explained, if Alice tweets at Bob to tell him her detector setting, that interference makes ruling out hidden variables impossible.

Closing the locality loophole is easier said than done. The detector setting must be quickly changed while photons are on the fly—“quickly” meaning in a matter of mere nanoseconds. In 1976 a young French expert in optics, Alain Aspect, proposed a way to carry out this ultraspeedy switch. His group’s experimental results, published in 1982, only bolstered Clauser’s results: local hidden variables looked extremely unlikely. “Perhaps Nature is not so queer as quantum mechanics,” Bell wrote in response to Aspect’s test. “But the experimental situation is not very encouraging from this point of view.”

Other loopholes remained, however, and Bell died in 1990 without witnessing their closure. Even Aspect’s experiment had not fully ruled out local effects, because it took place over too small a distance. Similarly, as Clauser and others had realized, if Alice and Bob detected an unrepresentative sample of particles—like a survey that contacted only right-handed people—their experiments could reach the wrong conclusions.

No one pounced to close these loopholes with more gusto than Anton Zeilinger, an ambitious, gregarious Austrian physicist. In 1997 he and his team improved on Aspect’s earlier work by conducting a Bell test over a then unprecedented distance of nearly half a kilometer. The era of divining reality’s nonlocality from kayak-size experiments had drawn to a close. Finally, in 2013, Zeilinger’s group took the next logical step, tackling multiple loopholes at the same time.

“Before quantum mechanics, I actually was interested in engineering. I like building things with my hands,” says Marissa Giustina, a quantum researcher at Google who worked with Zeilinger. “In retrospect, a loophole-free Bell experiment is a giant systems-engineering project.” One requirement for creating an experiment closing multiple loopholes was finding a perfectly straight, unoccupied 60-meter tunnel with access to fiber-optic cables. As it turned out, the dungeon of Vienna’s Hofburg palace was an almost ideal setting—aside from being caked with a century’s worth of dust. Their results, published in 2015, coincided with similar tests from two other groups that also found quantum mechanics as flawless as ever.

BELL’S TEST REACHES THE STARS

One great final loophole remained to be closed—or at least narrowed. Any prior physical connection between components, no matter how distant in the past, has the potential to interfere with the validity of a Bell test’s results. If Alice shakes Bob’s hand prior to departing on a spaceship, they share a past. It is seemingly implausible that a local hidden variable theory would exploit these kinds of loopholes, but it was still possible.

Today quantum information science is among the most vibrant subfields in all of physics.

In 2016 a team that included Kaiser and Zeilinger performed a cosmic Bell test. Using telescopes in the Canary Islands, the researchers sourced random decisions for detector settings from stars sufficiently far apart in the sky that light from one would not reach the other for hundreds of years, ensuring a centuries-spanning gap in their shared cosmic past. Yet even then, quantum mechanics again proved triumphant.

One of the principal difficulties in explaining the importance of Bell tests to the public—as well as to skeptical physicists—is the perception that the veracity of quantum mechanics was a foregone conclusion. After all, researchers have measured many key aspects of quantum mechanics to a precision of greater than 10 parts in a billion. “I actually didn’t want to work on it,” Giustina says. “I thought, like, ‘Come on, this is old physics. We all know what’s going to happen.’” But the accuracy of quantum mechanics could not rule out the possibility of local hidden variables; only Bell tests could do that.

“What drew each of these Nobel recipients to the topic, and what drew John Bell himself to the topic, was indeed [the question], ‘Can the world work that way?’” Kaiser says. “And how do we really know with confidence?” What Bell tests allow physicists to do is remove the bias of anthropocentric aesthetic judgments from the equation. They purge from their work the parts of human cognition that recoil at the possibility of eerily inexplicable entanglement or that scoff at hidden variable theories as just more debates over how many angels may dance on the head of a pin.

The 2022 award honors Clauser, Aspect and Zeilinger, but it is testament to all the researchers who were unsatisfied with superficial explanations about quantum mechanics and who asked their questions even when doing so was unpopular. “Bell tests,” Giustina concludes, “are a very useful way of looking at reality.”

Dan Garisto is a freelance science journalist.

- Login / Sign Up

Believe that journalism can make a difference

If you believe in the work we do at Vox, please support us by becoming a member. Our mission has never been more urgent. But our work isn’t easy. It requires resources, dedication, and independence. And that’s where you come in.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The Stanford Prison Experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud.

The most famous psychological studies are often wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. Textbooks need to catch up.

by Brian Resnick

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The study took paid participants and assigned them to be “inmates” or “guards” in a mock prison at Stanford University. Soon after the experiment began, the “guards” began mistreating the “prisoners,” implying evil is brought out by circumstance. The authors, in their conclusions, suggested innocent people, thrown into a situation where they have power over others, will begin to abuse that power. And people who are put into a situation where they are powerless will be driven to submission, even madness.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically . It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony .

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

- Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work

A new exposé published by Medium based on previously unpublished recordings of Philip Zimbardo, the Stanford psychologist who ran the study, and interviews with his participants, offers convincing evidence that the guards in the experiment were coached to be cruel. It also shows that the experiment’s most memorable moment — of a prisoner descending into a screaming fit, proclaiming, “I’m burning up inside!” — was the result of the prisoner acting. “I took it as a kind of an improv exercise,” one of the guards told reporter Ben Blum . “I believed that I was doing what the researchers wanted me to do.”

The findings have long been subject to scrutiny — many think of them as more of a dramatic demonstration , a sort-of academic reality show, than a serious bit of science. But these new revelations incited an immediate response. “We must stop celebrating this work,” personality psychologist Simine Vazire tweeted , in response to the article . “It’s anti-scientific. Get it out of textbooks.” Many other psychologists have expressed similar sentiments.

( Update : Since this article published, the journal American Psychologist has published a thorough debunking of the Stanford Prison Experiment that goes beyond what Blum found in his piece. There’s even more evidence that the “guards” knew the results that Zimbardo wanted to produce, and were trained to meet his goals. It also provides evidence that the conclusions of the experiment were predetermined.)

Many of the classic show-stopping experiments in psychology have lately turned out to be wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. And in recent years, social scientists have begun to reckon with the truth that their old work needs a redo, the “ replication crisis .” But there’s been a lag — in the popular consciousness and in how psychology is taught by teachers and textbooks. It’s time to catch up.

Many classic findings in psychology have been reevaluated recently

The Zimbardo prison experiment is not the only classic study that has been recently scrutinized, reevaluated, or outright exposed as a fraud. Recently, science journalist Gina Perry found that the infamous “Robbers Cave“ experiment in the 1950s — in which young boys at summer camp were essentially manipulated into joining warring factions — was a do-over from a failed previous version of an experiment, which the scientists never mentioned in an academic paper. That’s a glaring omission. It’s wrong to throw out data that refutes your hypothesis and only publicize data that supports it.

Perry has also revealed inconsistencies in another major early work in psychology: the Milgram electroshock test, in which participants were told by an authority figure to deliver seemingly lethal doses of electricity to an unseen hapless soul. Her investigations show some evidence of researchers going off the study script and possibly coercing participants to deliver the desired results. (Somewhat ironically, the new revelations about the prison experiment also show the power an authority figure — in this case Zimbardo himself and his “warden” — has in manipulating others to be cruel.)

- The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on lies. Hear them for yourself.

Other studies have been reevaluated for more honest, methodological snafus. Recently, I wrote about the “marshmallow test,” a series of studies from the early ’90s that suggested the ability to delay gratification at a young age is correlated with success later in life . New research finds that if the original marshmallow test authors had a larger sample size, and greater research controls, their results would not have been the showstoppers they were in the ’90s. I can list so many more textbook psychology findings that have either not replicated, or are currently in the midst of a serious reevaluation.

- Social priming: People who read “old”-sounding words (like “nursing home”) were more likely to walk slowly — showing how our brains can be subtly “primed” with thoughts and actions.

- The facial feedback hypothesis: Merely activating muscles around the mouth caused people to become happier — demonstrating how our bodies tell our brains what emotions to feel.

- Stereotype threat: Minorities and maligned social groups don’t perform as well on tests due to anxieties about becoming a stereotype themselves.

- Ego depletion: The idea that willpower is a finite mental resource.

Alas, the past few years have brought about a reckoning for these ideas and social psychology as a whole.

Many psychological theories have been debunked or diminished in rigorous replication attempts. Psychologists are now realizing it’s more likely that false positives will make it through to publication than inconclusive results. And they’ve realized that experimental methods commonly used just a few years ago aren’t rigorous enough. For instance, it used to be commonplace for scientists to publish experiments that sampled about 50 undergraduate students. Today, scientists realize this is a recipe for false positives , and strive for sample sizes in the hundreds and ideally from a more representative subject pool.

Nevertheless, in so many of these cases, scientists have moved on and corrected errors, and are still doing well-intentioned work to understand the heart of humanity. For instance, work on one of psychology’s oldest fixations — dehumanization, the ability to see another as less than human — continues with methodological rigor, helping us understand the modern-day maltreatment of Muslims and immigrants in America.

In some cases, time has shown that flawed original experiments offer worthwhile reexamination. The original Milgram experiment was flawed. But at least its study design — which brings in participants to administer shocks (not actually carried out) to punish others for failing at a memory test — is basically repeatable today with some ethical tweaks.

And it seems like Milgram’s conclusions may hold up: In a recent study, many people found demands from an authority figure to be a compelling reason to shock another. However, it’s possible, due to something known as the file-drawer effect, that failed replications of the Milgram experiment have not been published. Replication attempts at the Stanford prison study, on the other hand, have been a mess .

In science, too often, the first demonstration of an idea becomes the lasting one — in both pop culture and academia. But this isn’t how science is supposed to work at all!

Science is a frustrating, iterative process. When we communicate it, we need to get beyond the idea that a single, stunning study ought to last the test of time. Scientists know this as well, but their institutions have often discouraged them from replicating old work, instead of the pursuit of new and exciting, attention-grabbing studies. (Journalists are part of the problem too , imbuing small, insignificant studies with more importance and meaning than they’re due.)

Thankfully, there are researchers thinking very hard, and very earnestly, on trying to make psychology a more replicable, robust science. There’s even a whole Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science devoted to these issues.

Follow-up results tend to be less dramatic than original findings , but they are more useful in helping discover the truth. And it’s not that the Stanford Prison Experiment has no place in a classroom. It’s interesting as history. Psychologists like Zimbardo and Milgram were highly influenced by World War II. Their experiments were, in part, an attempt to figure out why ordinary people would fall for Nazism. That’s an important question, one that set the agenda for a huge amount of research in psychological science, and is still echoed in papers today.

Textbooks need to catch up

Psychology has changed tremendously over the past few years. Many studies used to teach the next generation of psychologists have been intensely scrutinized, and found to be in error. But troublingly, the textbooks have not been updated accordingly .

That’s the conclusion of a 2016 study in Current Psychology. “ By and large,” the study explains (emphasis mine):

introductory textbooks have difficulty accurately portraying controversial topics with care or, in some cases, simply avoid covering them at all. ... readers of introductory textbooks may be unintentionally misinformed on these topics.

The study authors — from Texas A&M and Stetson universities — gathered a stack of 24 popular introductory psych textbooks and began looking for coverage of 12 contested ideas or myths in psychology.

The ideas — like stereotype threat, the Mozart effect , and whether there’s a “narcissism epidemic” among millennials — have not necessarily been disproven. Nevertheless, there are credible and noteworthy studies that cast doubt on them. The list of ideas also included some urban legends — like the one about the brain only using 10 percent of its potential at any given time, and a debunked story about how bystanders refused to help a woman named Kitty Genovese while she was being murdered.

The researchers then rated the texts on how they handled these contested ideas. The results found a troubling amount of “biased” coverage on many of the topic areas.

But why wouldn’t these textbooks include more doubt? Replication, after all, is a cornerstone of any science.

One idea is that textbooks, in the pursuit of covering a wide range of topics, aren’t meant to be authoritative on these individual controversies. But something else might be going on. The study authors suggest these textbook authors are trying to “oversell” psychology as a discipline, to get more undergraduates to study it full time. (I have to admit that it might have worked on me back when I was an undeclared undergraduate.)

There are some caveats to mention with the study: One is that the 12 topics the authors chose to scrutinize are completely arbitrary. “And many other potential issues were left out of our analysis,” they note. Also, the textbooks included were printed in the spring of 2012; it’s possible they have been updated since then.

Recently, I asked on Twitter how intro psychology professors deal with inconsistencies in their textbooks. Their answers were simple. Some say they decided to get rid of textbooks (which save students money) and focus on teaching individual articles. Others have another solution that’s just as simple: “You point out the wrong, outdated, and less-than-replicable sections,” Daniël Lakens , a professor at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, said. He offered a useful example of one of the slides he uses in class.

Anecdotally, Illinois State University professor Joe Hilgard said he thinks his students appreciate “the ‘cutting-edge’ feeling from knowing something that the textbook didn’t.” (Also, who really, earnestly reads the textbook in an introductory college course?)

And it seems this type of teaching is catching on. A (not perfectly representative) recent survey of 262 psychology professors found more than half said replication issues impacted their teaching . On the other hand, 40 percent said they hadn’t. So whether students are exposed to the recent reckoning is all up to the teachers they have.

If it’s true that textbooks and teachers are still neglecting to cover replication issues, then I’d argue they are actually underselling the science. To teach the “replication crisis” is to teach students that science strives to be self-correcting. It would instill in them the value that science ought to be reproducible.

Understanding human behavior is a hard problem. Finding out the answers shouldn’t be easy. If anything, that should give students more motivation to become the generation of scientists who get it right.

“Textbooks may be missing an opportunity for myth busting,” the Current Psychology study’s authors write. That’s, ideally, what young scientist ought to learn: how to bust myths and find the truth.

Further reading: Psychology’s “replication crisis”

- The replication crisis, explained. Psychology is currently undergoing a painful period of introspection. It will emerge stronger than before.

- The “marshmallow test” said patience was a key to success. A new replication tells us s’more.

- The 7 biggest problems facing science, according to 270 scientists

- What a nerdy debate about p-values shows about science — and how to fix it

- Science is often flawed. It’s time we embraced that.

Most Popular

- You’re being lied to about “ultra-processed” foods

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- Everyone’s favorite frustrating, hard-to-clean, potentially dangerous household device

- The Air Quality Index and how to use it, explained

- The people who deliver your Amazon packages are striking. Here’s why.

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

Our earliest studies of Neanderthals were fundamentally flawed.

DMT, “the nuclear bomb of the psychedelic family,” explained.

It turns out cleaning your hands is more complicated than killing germs.

When you were born is actually an important risk factor for cancer.

We need new malaria drugs — so I spent a year as a guinea pig.

Xenotransplantation raises major moral questions — and not just about the pigs.

- Naked Science Forum

- General Science

Motivational 'fleas in a jar' video - is it real or fake?

- 27143 Views

0 Members and 1 Guest are viewing this topic.

mattmckee (OP)

- Activity: 0%

- Naked Science Forum King!

- Thanked: 61 times

- Site Moderator

Re: Motivational 'fleas in a jar' video - is it real or fake?

Similar topics (5).

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Aug 27, 2013 · An account describing the horrific results of a 'Russian Sleep Experiment' from the late 1940s is a work of modern creepy fiction. David Mikkelson Published Aug. 27, 2013

Jul 28, 2022 · The Russian Sleep Experiment is a popular urban myth which began to circulate online in "creepypasta" forums (so-named for the ease with which you could copy-paste spooky content) in the early 2010s.

Nov 11, 2020 · If you've seen 4 forks and 4 batteries surrounding a coin and suddenly making it spin, find out here if it's real or fake. Is it science or is it a magic tr...

Jan 25, 2022 · The Russian Sleep Experiment purports to recount an experiment that took place at a test facility in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s. In a military-sanctioned scientific experiment, five political prisoners were kept in a sealed gas chamber, with a continually administered airborne stimulant for the purpose of keeping the subjects awake for ...

The story recounts an experiment set in 1947 at a covert Soviet test facility, where scientists give test subjects a stimulant gas that would prevent sleep. As the experiment progresses, it is shown that the lack of sleep transforms the subjects into violent zombie-like creatures who are addicted to the gas. At the end of the story, every ...

Oct 26, 2018 · Thinking about the science that made Frankenstein seem so real in 1818 might help us consider more carefully the ways we think now about the possibilities – and the dangers – of our present ...

Oct 6, 2022 · In the eponymous Bell test (an evolution of the EPR thought experiment), Alice and Bob receive the same paired particles, but now they each have two different detector settings—A and a, B and b.

Jun 13, 2018 · The Zimbardo prison experiment is not the only classic study that has been recently scrutinized, reevaluated, or outright exposed as a fraud. Recently, science journalist Gina Perry found that the ...

Is White Choccy real choccy ? Started by neilep Board General Science. Replies: 9 Views: 13498 16/04/2008 09:04:10 by DoctorBeaver: Is this fools gold or real gold? Started by Sweetc Board Geology, Palaeontology & Archaeology. Replies: 8 Views: 13242 22/05/2018 21:31:11 by Bass: Acrylic Glass Versus Real Glass. Started by neilep Board Chemistry ...

Oct 5, 2021 · There is this famous experiment (legit or fake, it doesn’t really matter) in which a number of fleas are placed in a jar. Since their nature is to jump high — up to 100 times their weight ...