- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 September 2024

Strategies to improve the implementation of preventive care in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Laura Heath ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1628-1981 1 ,

- Richard Stevens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9258-4060 1 ,

- Brian D. Nicholson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0661-7362 1 ,

- Joseph Wherton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7701-4783 1 ,

- Min Gao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6196-7088 1 ,

- Caitriona Callan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5906-9542 1 ,

- Simona Haasova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3993-0462 1 , 2 &

- Paul Aveyard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1802-4217 1

BMC Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 412 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1728 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Action on smoking, obesity, excess alcohol, and physical inactivity in primary care is effective and cost-effective, but implementation is low. The aim was to examine the effectiveness of strategies to increase the implementation of preventive healthcare in primary care.

CINAHL, CENTRAL, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Dissertations & Theses – Global, Embase, Europe PMC, MEDLINE and PsycINFO were searched from inception through 5 October 2023 with no date of publication or language limits. Randomised trials, non-randomised trials, controlled before-after studies and interrupted time series studies comparing implementation strategies (team changes; changes to the electronic patient registry; facilitated relay of information; continuous quality improvement; clinician education; clinical reminders; financial incentives or multicomponent interventions) to usual care were included. Two reviewers screened studies, extracted data, and assessed bias with an adapted Cochrane risk of bias tool for Effective Practice and Organisation of Care reviews. Meta-analysis was conducted with random-effects models. Narrative synthesis was conducted where meta-analysis was not possible. Outcome measures included process and behavioural outcomes at the closest point to 12 months for each implementation strategy.

Eighty-five studies were included comprising of 4,210,946 participants from 3713 clusters in 71 cluster trials, 6748 participants in 5 randomised trials, 5,966,552 participants in 8 interrupted time series, and 176,061 participants in 1 controlled before after study. There was evidence that clinical reminders (OR 3.46; 95% CI 1.72–6.96; I 2 = 89.4%), clinician education (OR 1.89; 95% CI 1.46–2.46; I 2 = 80.6%), facilitated relay of information (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.10–3.46, I 2 = 88.2%), and multicomponent interventions (OR 3.10; 95% CI 1.60–5.99, I 2 = 96.1%) increased processes of care. Multicomponent intervention results were robust to sensitivity analysis. There was no evidence that other implementation strategies affected processes of care or that any of the implementation strategies improved behavioural outcomes. No studies reported on interventions specifically designed for remote consultations. Limitations included high statistical heterogeneity and many studies did not account for clustering.

Conclusions

Multicomponent interventions may be the most effective implementation strategy. There was no evidence that implementation interventions improved behavioural outcomes.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42022350912.

Peer Review reports

Smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and physical inactivity bring forward the onset of chronic disease, multimorbidity, and premature death. Compared to individuals with no behavioural risk factors, those with 2 or more risk factors (smoking, obesity, alcohol intake and physical inactivity) can expect to live on average 12 years fewer [ 1 ]. In 2015, 30.3% and 15.5% of global disease burden were accounted for by behavioural factors and metabolic factors, respectively [ 2 ]. Differences in the prevalence of these risk factors explain a substantial portion of the health gap between those from affluent and deprived areas [ 3 , 4 ]. One way health systems address this is through preventive healthcare. This includes supporting behaviour change via brief opportunistic interventions and referral to further support [ 5 , 6 ]. Systematic reviews of randomised trials and modelling from their results show that opportunistic screening for and intervention to support behaviour change is effective and cost-saving for smoking cessation [ 7 , 8 ]; effective and cost-effective for reducing hazardous drinking [ 9 , 10 ]; effective and cost-effective for weight loss in obesity [ 11 , 12 ]; effective and may be cost-effective for physical inactivity [ 5 , 13 ].

These behaviour changes reduce the development of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and premature mortality [ 14 ]. They have been shown to be feasible in primary care and equitable in their impact [ 15 ]. Increasing preventive care delivery can also reduce the environmental impact of healthcare and support the transition to more sustainable healthcare systems [ 16 ]. Optimising the implementation of these evidence-based interventions is a health system priority [ 17 ]. However, the rate of intervention by primary healthcare professionals, who are well-placed to deliver them, is low [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. For example, in the UK in 2020, the rate of advice for weight management (8 events per hundred patients per year), physical inactivity (4 events per hundred patients per year) and excessive alcohol intake (4 events per hundred patients per year) was low compared to the prevalence of overweight or obesity (approximately 60%), of physical inactivity (approximately 30%) and of harmful alcohol consumption (approximately 20%) [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Given their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, governments and health systems have attempted to increase the implementation of this type of preventive healthcare [ 17 , 24 ]. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of different implementation strategies (Table 1 ) compared to usual care, in adults in a primary healthcare setting to increase both process and behavioural outcomes for smoking, obesity, excessive alcohol consumption and physical inactivity.

The way primary health care is being delivered is also changing as more consultations are being delivered remotely (via telephone, video, email or text message), and this may affect implementation efforts [ 25 , 26 ]. Therefore, we also aimed to examine the effectiveness of implementation strategies in this current context.

A full protocol was prospectively published on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) [ 27 ]. This followed the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) guidelines for an implementation systematic review and is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [ 28 , 29 ].

Data sources and searches

We searched the Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Dissertations & Theses – Global, Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), Europe PubMed Central (PMC), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and PsycINFO for studies until 5th October 2023. The references of included studies were manually searched for studies missed in the database search. The complete database search strategy is included in Additional file 1.

Study selection

The population considered for inclusion were adult patients seeking primary health care, where interventions for behaviour change happen opportunistically. If adolescents were also included in the study population, we only analysed the participants over the age of 18. If it was not possible to separate those under 18 from adult participants, we only included the study if the average age of participants was over 18 years. In this review, we use the National Health Service (NHS) England definition of primary care, including the general practice multidisciplinary team, community pharmacy, dental and optometry services [ 30 ]. When it was unclear whether a study was conducted in primary care, a decision was made in consultation with the wider research team which included three primary care physicians, considering whether this was the first point of contact for the patient in the healthcare system. We included cluster randomised trials (cRT), cluster non-randomised trials (cNRT), randomised trials (RT), controlled before-after studies (CBA) and interrupted time series (ITS) studies.

Exclusion criteria were adults seeking care for established disease, e.g. weight loss as a treatment for type 2 diabetes, and people who were receiving palliative care. There were no date or language restrictions.

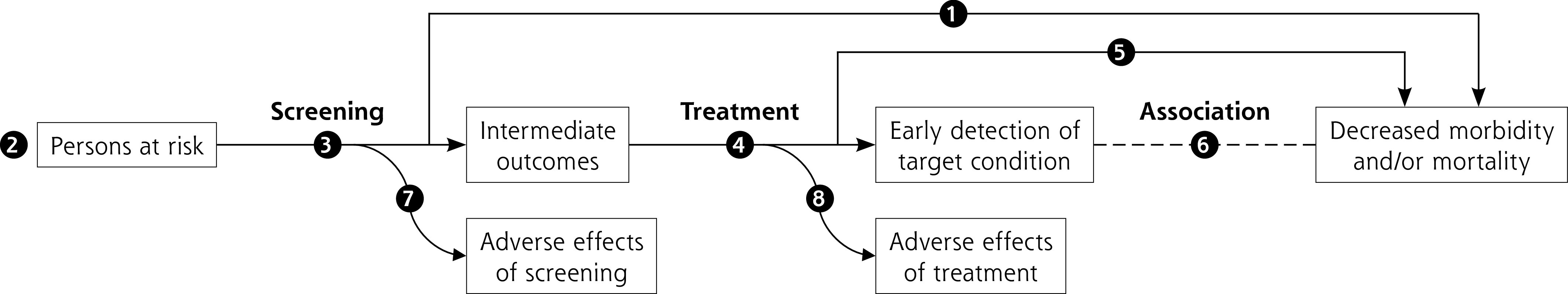

Interventions included were those both at the health system and health professional level and these were compared to usual care. We included interventions that used one of ten implementation strategies (Table 1 ) to encourage action on smoking, poor diet, alcohol consumption or physical inactivity. This taxonomy of implementation strategies was adapted from the taxonomy used by the Cochrane EPOC group [ 31 , 32 ]. A similar approach has been used in another study looking at implementation strategies to optimise care for type 2 diabetes [ 33 ].

After deduplication, two reviewers independently screened title and abstracts and then full-text records against prespecified eligibility criteria using a decision flowchart. Covidence screening software (Veritas Health Innovation) was used for deduplication and title, abstract, and full-text screening [ 34 ].

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were then extracted independently by two reviewers using a piloted Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Extracted information included baseline characteristics, study design, intervention characteristics and outcome measures. Risk of bias was independently assessed by two authors using the Cochrane EPOC risk of bias tool for the appropriate study design. Disagreements were resolved by the wider team for review.

Data synthesis and analysis

In line with Donabedian’s three-component approach for measuring the quality of care, the main outcomes were measures that record changes in process (e.g. referral to further support) and behavioural outcome (e.g. smoking cessation or weight loss) of preventive care [ 35 ]. Outcomes were grouped by predominant mode of intervention e.g., clinician education or team changes. Outcomes were extracted at 1 year, or the closest measurement to this. Secondary outcomes included patient acceptability and satisfaction with the intervention; healthcare professional acceptability and satisfaction with the intervention; resource use; equity impact, and adverse effects.

Where more than one health behaviour was reported we prioritised a summary statistic of the effect of the intervention on combined health behaviours, the primary outcome of the study, or if neither of these were present, the first reported health behaviour. If more than one process outcome was reported, we took the most distal outcome, e.g. if advice given and referral made were both reported, we used the referral data. We included studies that reported changes in health behaviours (e.g. diet) and outcomes of health behaviours (e.g. weight) and grouped these together for the behavioural outcomes meta-analysis.

We extracted continuous and dichotomous outcomes, converting these where required from a standardised effect measure to an odds ratio (OR) using an adapted Chinn’s method [ 36 ]. Where a study did not correct for clustering, we adjusted the width of the confidence interval as described in the Cochrane handbook [ 37 ]. The upper quartile intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) was selected from the included studies. This conservative approach also reduces the influence of outlier values. When the number of cases in the intervention or control group was zero, the Peto method was used to calculate an OR. Calculation details can be found in Additional file 2.

Where an adjusted hazard ratio, incident rate ratio or risk ratio was given by the study, this was taken as a conservative estimate of the odds ratio. If two or more intervention groups existed, we selected the intervention group that most closely represented the implementation strategy of interest. For example, we used the training workshop and usual care arms, and not the free patient education material arm in the Kottke et al. study [ 38 ]. Where there were intervention arms of different intensities, these were combined into a single intervention arm. Some studies provided insufficient information to calculate a standardised effect measure. In these cases, the authors were contacted and if no further information was provided, these results were synthesised narratively.

We used random effects meta-analysis to pool study outcomes, given that the true effect of preventive interventions is likely to differ across contexts and health behaviours. Sensitivity analysis (Additional file 3: Fig. S1–S2) used two further models to pool the study outcomes. Firstly, the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) model variance correction was applied to the standard DerSimonian-Laird model; optionally without truncation of correction factor at 1, to reduce the risk of poor coverage of 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Secondly, the inverse variance heterogeneity (IVhet) model, for meta-analysis of heterogenous studies [ 39 , 40 ]. Meta-analysis was conducted in Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp) using the admetan command. The full Stata code is available in Additional file 4. Forest plots were used to display the results of meta-analysis. The I 2 statistic and 95% prediction intervals were calculated to assess heterogeneity.

Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted where possible, excluding firstly studies at high risk of bias, secondly studies where data had to be imputed (Additional file 3: Fig. S3–S4), and lastly when outcomes of health behaviours were reported (e.g. weight) rather than the health behaviour directly (e.g. diet) (Additional file 3: Fig. S5). Subgroup analysis considered each health behaviour separately (Additional file 3: Fig. S6–S7). These analyses were completed where there was more than one study able to be meta-analysed in each subgroup.

Role of the funding source

This review was funded by the Wellcome Trust who had no role in the design of the study or analysis or interpretation of the data.

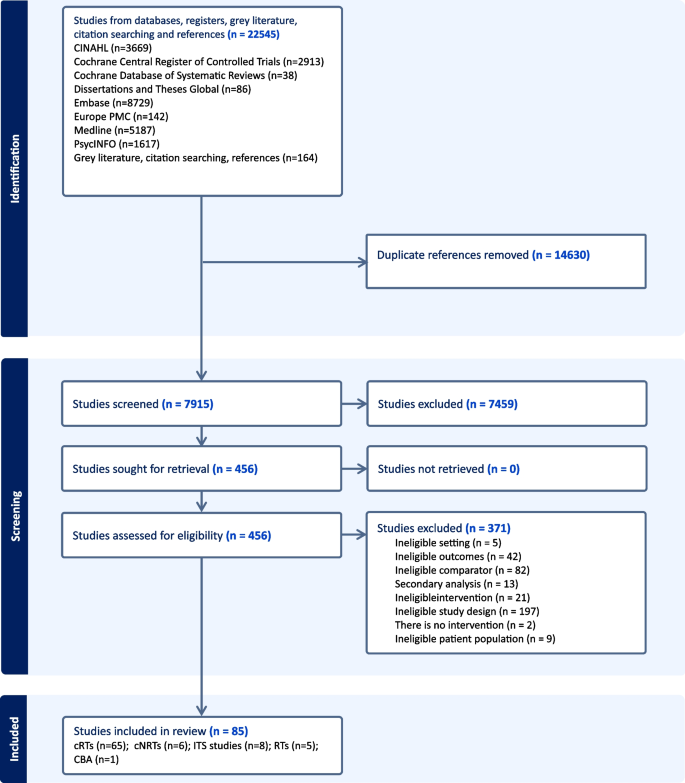

Figure 1 shows the flow through the study. The search identified 22,545 unique study titles. After screening, 456 full texts were assessed for eligibility and 85 studies were included.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics

Of the 85 included studies (Additional file 4: Table S1), [ 38 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 ] 65 were cRTs, 6 were cNRTs, 8 were ITS studies, 5 were RTs and 1 was a CBA study. The 71 cluster trials had a total of 3713 clusters and 4,210,946 participants. The randomised trials had a total of 6748 participants, the interrupted time series studies used data from 5,966,552 participants 176,061 participants in 1 CBA study. Forty-two studies focussed on smoking, 19 on alcohol, 7 on obesity (poor diet), 2 on physical activity and 15 on multiple health behaviours. The average age of patients and healthcare professionals was 49 and 43 years, respectively. Forty-eight per cent of patients and 45% of healthcare professionals were male. Of the small number of studies that reported ethnicity, 67% of patients and 69% of healthcare professionals were White. The most common countries were the USA ( n = 42), Europe ( n = 15) and the UK ( n = 13). The mean (standard deviation) follow-up time for ITS studies was 44 (42) months and for the other study types was 10 (6) months.

No studies examined the impact of preventive care management interventions or audit and feedback interventions. Three studies investigated the impact of team changes; 5 studies investigated the electronic patient registry; 5 studies investigated the facilitated relay of information; 1 study investigated continuous quality improvement; 37 studies investigated clinician education interventions; 9 investigated clinical reminders; 7 investigated financial incentives and 18 investigated multi-component interventions. Of the studies, 68 were included in meta-analyses and 17 studies were synthesised narratively. No studies examined implementation strategies specifically for remote consultations in primary care.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed to be low in 25 studies, unclear in 24 studies and high in 36 studies (Tables 2 and 3 ). Removing studies at high risk of bias in the sensitivity analysis did not significantly change the meta-analysis results (Additional file 3: Fig S3–S4).

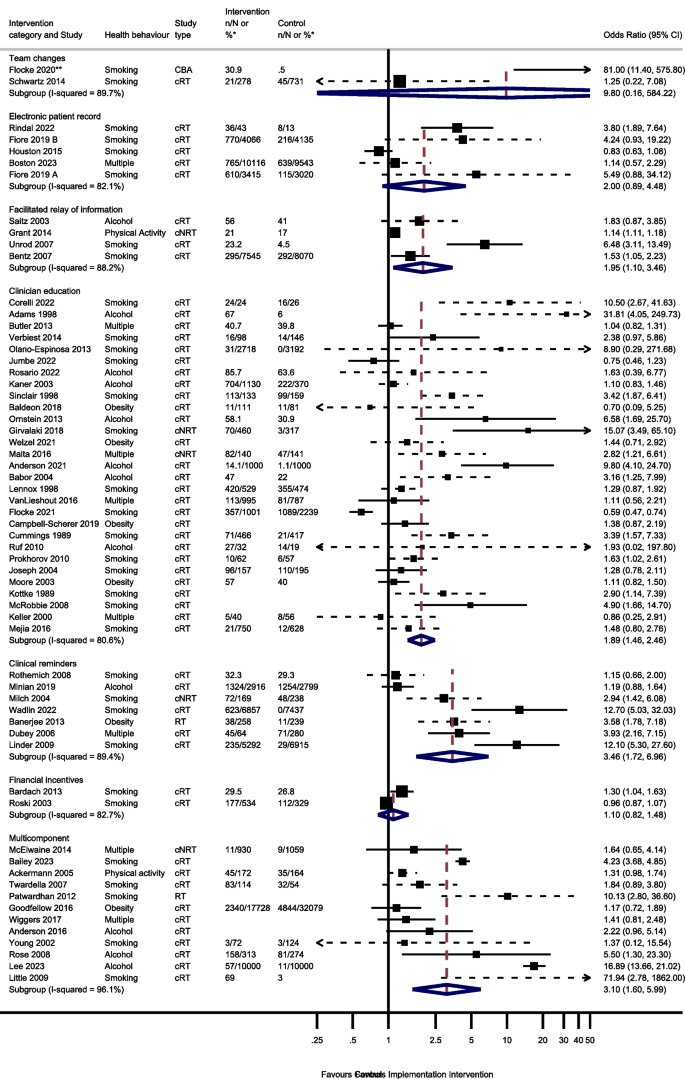

Process outcomes

Sixty studies were included in the process outcome meta-analysis from 7 intervention groups: 7 clinical reminder studies; 29 clinician education studies, 4 electronic patient registry studies, 4 facilitated relay of information studies, 2 financial incentive studies, 12 multi-component studies and 2 team change studies (Fig. 2 ).

Odds of improving process outcomes between implementation interventions and control groups using random effects meta-analysis

*n/N or % given where available in the paper. ** Flocke study estimate not visible for reasons of scale. Note: Dashed line indicates studies for which approximate data had to be used

Three studies reported the effect of team changes on process outcomes. One ITS study was not included in the meta-analysis. This study found team changes resulted in a significant increase in the number of people receiving an appropriate weight management referral or smoking cessation intervention [ 44 ]. The meta-analysis of the remaining 2 studies reported imprecise results (OR 9.80, 95% CI 0.16–584.22, I 2 = 89.7%, 95% CI 62–97%).

Four studies examined the effect of changing the electronic patient record. One of the 4 electronic patient record studies had 2 separate analyses for 2 different healthcare systems [ 66 ]. There was no evidence that amending the electronic patient record increased preventive processes (OR 2.00; 95% CI 0.89–4.48, I 2 = 82.1%, 95% CI 59–92%).

Five studies reported the effect of the facilitated relay of information on preventive care, with 4 included in the meta-analysis. One study was unable to complete clinician and practice level analyses because the sample was too small [ 128 ]. There was evidence that facilitated relay of information interventions significantly increased preventive processes (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.10–3.46, I 2 = 88.2%, 95% CI 72–95%).

Thirty-one studies examined the effects on process outcomes of clinician education interventions. Two studies were unable to be included in the analysis [ 69 , 80 ]. One study showed no evidence of a significant difference between intervention and control groups being signposted to quitline services by pharmacy staff [ 80 ]. The second study found that training and support for GPs significantly increased the rate of implementation of brief interventions for alcohol [ 69 ]. Meta-analysis of the remaining 29 studies showed a significant increase in preventive process outcomes (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.46–2.46, I 2 = 80.6%, 95% CI 73–86%).

Seven of the 8 clinical reminder studies with process outcomes were able to be meta-analysed. These showed a statistically significant increase in health process outcomes (OR 3.46, 95% CI 1.72–6.96, I 2 = 89.4%, 95% CI 81–94%). One study not included in the meta-analysis reported that there were no significant differences between groups in changes in the percentages of patients who had a nutrition counselling visit when reminders and alerts were added to the records of patients with overweight or obesity [ 135 ].

Six studies reported the effect of financial incentives on process outcomes. There were differences in the way that results were reported for four ITS studies, precluding meta-analysis. Three reported statistically significant positive associations between financial incentives and greater alcohol and smoking advice/interventions, [ 100 , 122 , 136 ] and one reported a positive association between the financial incentive and clinicians’ alcohol advice or intervention without commenting on statistical significance [ 106 ]. Two cRTs reported process outcomes [ 55 , 111 ]. There was no evidence from the meta-analysis of these studies that financial incentives increased the delivery of preventive processes (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.82–1.48, I 2 = 82.7%, 95% CI 27–96%).

Seventeen multicomponent intervention studies reported process outcomes, of which 12 were included in the meta-analysis. Two ITS studies not included in the meta-analysis found that multicomponent interventions were associated with an increase in the number of people screened for tobacco use or receiving a smoking cessation intervention, [ 52 ] and an increase in alcohol recording [ 125 ]. One study not included in the meta-analysis found a statistical increase in the percentage of tobacco users who received a cessation intervention [ 85 ]. However, another study not included in the meta-analysis reported no evidence that patients were more likely to receive behavioural advice or referral at follow-up for any health behaviour, [ 74 ] and another found no evidence for a change in alcohol screening after implementing a multicomponent intervention [ 125 ]. Of the 12 studies included in the meta-analysis, there was evidence that multicomponent interventions increased the process outcomes (OR 3.10, 95% CI 1.60–5.99, I 2 = 96.1%, 95% CI 95–97%).

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

Sensitivity analysis showed that multicomponent interventions were the only category of intervention that showed evidence of increased process outcomes in all 3 meta-analysis models (random effects, HKSJ, and IVhet) (Additional file 3: Fig. S1). Removing studies at high risk of bias or studies that required imputed data did not significantly change the results (Additional file 3: Fig. S3). Subgroup analysis showed that there was no evidence that clinician education or multicomponent interventions that targeted multiple health behaviours increased process outcomes (Additional file 3: Fig. S6).

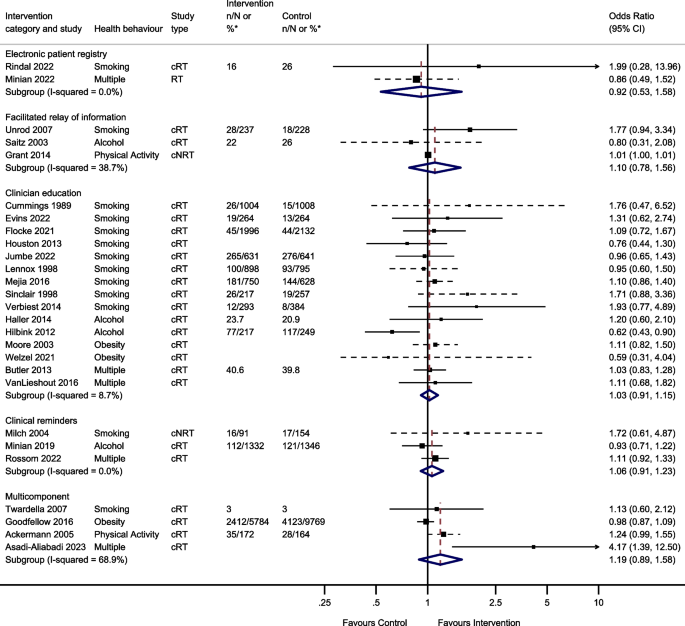

Behavioural outcomes

Thirty-nine studies reported behavioural outcomes and were able to be meta-analysed, assessing the effect of 5 intervention modes. This included 15 studies of clinician education; 3 studies of clinical reminders; 2 electronic patient registry studies; 3 facilitated relay of information studies, and 4 studies of multicomponent interventions (Fig. 3 ).

Odds of improving behavioural outcomes between implementation interventions and control groups using random effects meta-analysis

*n/N or % given where available in the paper. Note: Dashed line indicates studies for which approximate data had to be used

Two studies reported the effect of team changes on behavioural outcomes. These were unable to be meta-analysed due to differences in the reporting of data. One found that individuals who were in the intervention group were significantly more likely than controls to have a lower body mass index (BMI) and to have quit smoking at the end of the follow-up period, [ 44 ] the other found no evidence of a difference in self-reported smoking cessation at 8 months [ 117 ].

Two studies investigated the effect of changes to the electronic patient record on behavioural outcomes and were meta-analysed. There was no evidence that changes to the electronic patient registry improved behavioural outcomes (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.53–1.58, I 2 = 0.0%, 95% CI 0–100%).

Four studies reported the effect of facilitated relay of information on beneficial behavioural outcomes. One study was unable to complete clinician and practice level analyses because the sample was too small [ 128 ]. Three studies included in the meta-analysis found no evidence that facilitated relay of information improved behavioural outcomes (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.78–1.56, I 2 = 38.7%, 95% CI 0–81%).

One study investigated the effect of continuous quality improvement on smoking outcomes [ 133 ]. There was no evidence of a difference in smoking cessation between the intervention and the control groups (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.58–1.39).

Twenty studies reported the effect of clinician education on behavioural outcomes. Five were unable to be included in the meta-analysis due to insufficient information. One study showed a significant increase in smoking cessation in the intervention group compared to controls at 1 year [ 101 ]. Another study found the intervention group had a greater reduction in alcohol dependence score during follow-up compared to the control group [ 105 ]. However, three studies found no evidence of a difference in rates of smoking cessation, alcohol dependence score or difference in BMI/ weight between intervention and control groups during follow-up [ 38 , 53 , 115 ]. The meta-analysis showed there was no evidence that clinician education (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.91–1.15, I 2 = 8.7%, 95% CI 0–46%) improved behavioural outcomes.

Four studies reported the effect of clinical reminders on beneficial behavioural outcomes. One study not included in the meta-analysis due to insufficient data showed no evidence of a difference in weight loss between intervention and control groups [ 50 ]. The remaining 3 studies included in the meta-analysis showed no evidence that clinical reminders improved behavioural outcomes (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.91–1.23, I 2 = 0.0%, 95% CI 0–11%).

Two studies reported the effect of financial incentives on behavioural outcomes. One was an ITS study, and the other was a cRT. Due to the difference in reporting of data, these were unable to be meta-analysed. One reported that financial incentives were significantly associated with reduced smoking, but not with reduced BMI or alcohol consumption in the 6 years following the introduction of the financial incentive [ 65 ]. The other showed there was no evidence of an effect of financial incentives on smoking cessation at 6 months [ 111 ].

Four studies reported the effect of multicomponent interventions. There was no evidence that multicomponent interventions improved behavioural outcomes (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.89–1.58, I 2 = 68.9%, 95% CI 10–89%).

Sensitivity analysis showed no significant difference in meta-analysis results using different models (random effects, HKSJ, and IVhet) (Additional file 3: Fig. S2), when excluding studies at high risk of bias, or studies that used imputed data (Additional file 3: Fig. S4). Due to the small number of studies in the meta-analysis, subgroup analysis was only conducted for clinician education studies. There was no evidence that the effect of clinician education varied between smoking, alcohol, obesity, or multiple behavioural outcomes (Additional file 3: Fig. S7). Removing the three studies that measured the outcome of a health behaviour (weight) rather than the health behaviour directly (diet) did not change the result of the meta-analysis (Additional file 3: Fig. S5) [ 71 , 98 , 130 ].

Secondary outcomes

Most studies did not report data on our secondary outcomes. Three studies reported no adverse effects of the intervention [ 41 , 64 , 82 ]. Thirteen studies reported that training received was useful, relevant, or increased healthcare professional confidence and self-esteem [ 61 , 70 , 71 , 75 , 82 , 90 , 104 , 105 , 108 , 120 , 127 , 130 , 134 ]. One electronic health record study commented that eReferral had good reach amongst people without health insurance, and this could help reduce health inequalities [ 66 ]. However, another study described how people from deprived communities and smokers were less likely to take up the offer of an additional health check [ 44 ].

One study reported on barriers to weight management in follow-up interviews. Healthcare professionals described how too many clinical reminders were counterproductive [ 50 ]. A clinical education smoking study in community pharmacies described time constraints, privacy, and part-time staff as barriers to maintaining an accurate clinical record [ 118 ]. Healthcare professionals in another clinical education study questioned whether in-depth training for weight management was feasible against other competing clinical demands [ 98 ].

Three studies presented data relevant to the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. One calculated the additional cost of clinician-specific feedback at US$65 per estimated quit [ 128 ]. Another clinical education study targeting smoking cessation, found the intervention incremental cost per life year gained after 6 months was €969 [ 101 ]. Finally, a clinical education study for excess alcohol found a similar cost-effectiveness ratio between control and intervention practices [ 83 ].

There was some evidence that many implementation strategies including clinical reminders, clinician education, facilitated relay of information and multicomponent interventions increased the occurrence of preventive processes of care. Multicomponent interventions were the most robust in sensitivity analysis. There was some evidence in subgroup analysis that implementation strategies that target multiple behaviours may be less effective than those that target single behaviours. However, there was no consistent evidence that these process changes translated into improved behavioural outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Our search strategy was thorough, including 8 databases, grey literature, references, and citation searching, with no date or language constraints. The resulting sample is large with data from over 10 million participants. Included studies came from North America, Europe, South America, the Middle East, and Australia so our results are relevant to many healthcare systems.

Dividing interventions into implementation categories allows the results to be relevant to policy makers and public health professionals, although for a few studies, the predominant implementation strategy was not clear. We resolved these through consensus of all investigators. We followed PRISMA guidance throughout this study (Additional file 6 and Additional file 7).

Many of our studies had a high risk of bias. This was partly due to our decision to include a greater range of study designs and include non-randomised studies. This decision was made as some interventions e.g., financial incentives implemented across an entire health care system cannot practically be randomised in a traditional trial setting. There was also high heterogeneity, especially in the primary analyses. This is not unexpected as, although interventions were of a similar type, they differed in intensity, duration, delivery, and format. In addition, studies were conducted in different countries, healthcare systems with different methods of usual care, and amongst different population demographics, which also likely contributed to the high heterogeneity. In the presence of such high heterogeneity, we considered it useful to conduct meta-analysis and examine statistical significance, but the individual point estimates should not be over-interpreted. Random-effects meta-analysis allows for differences in the intervention effect between studies and provides an estimate of the average intervention effect [ 137 ]. We also calculated prediction intervals for each meta-analysis conducted (Additional file 8: Table S1). These confirm the high levels of heterogeneity in the analysis, with a range of ORs plausible for different settings or populations. We did not formally assess for publication bias or other small study effects. We think it unlikely that unreported studies or results would change our conclusions. Only two studies reported information about how the intervention effectiveness differed between socioeconomic groups. Future studies should collect this information to understand which population groups may benefit most.

We had to impute several calculations as many studies had not accounted for clustering, or we had to calculate an OR from available data. Whilst these established methods, they introduce another opportunity for error. Resulting CIs were often wide, reflecting the uncertainty in data from single trials.

When analysing behavioural outcomes, we combined studies that targeted both behaviours directly and those that targeted outcomes of behaviours. One study measured alcohol dependence rather than consumption using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score [ 76 ]. However, this scoring system is strongly correlated with alcohol consumption, and so we retained this study in the meta-analysis [ 138 , 139 ]. Another study used a combined metric of smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity and diet [ 58 ]. We also retained this study in the meta-analysis as most of the measures used (smoking status, alcohol consumption and physical activity) were used by the other studies. It seems unlikely that including these studies would change the conclusion that there was no evidence of effect. Furthermore, a post hoc sensitivity analysis that excluded three studies that measured the outcome of a health behaviour (weight) rather than the health behaviour (diet) directly, did not change the result of the meta-analysis that there was no evidence of effect [ 71 , 98 , 130 ].

The observed difference in process and behavioural outcomes may be because outcomes can be measured more precisely in proximal (process) outcomes, behavioural outcomes take time to emerge, and many studies did not have sufficient follow-up periods to capture changes in patient behaviour. Furthermore, process outcomes are recorded at the time of consultation, while changes in behaviour may have occurred without the patient returning and/or the clinician asking about behaviour and recording the change at a subsequent consultation. Moreover, increases in the recording of processes of care may reflect that clinicians start recording activity that was previously unrecorded. If so, increases in processes of care may occur while changes in patient behaviour would not be expected to increase. This is particularly likely to occur where the intervention is a financial incentive. However, trial data has shown that genuine increases in process outcomes does translate into beneficial behavioural outcomes [ 11 ].

Comparison with existing literature

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate implementation strategies for preventive healthcare. Other studies have focussed on quality improvement strategies in chronic disease management or fall prevention. For example, systematic reviews investigating quality improvement strategies in diabetes care found that multicomponent QI programmes may achieve meaningful population improvements for most immediate diabetes outcomes and that interventions at the health system or patient level may be more effective than interventions at the health professional level [ 33 , 140 ]. A comprehensive systematic review looking at falls prevention found evidence that team changes and multicomponent interventions may reduce falls [ 141 ]. Another review reported that clinician education and patient reminders and education were the most effective strategies for reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure respectively [ 142 ]. Our review supports these findings for the implementation of preventive healthcare in primary care. This suggests that quality improvement strategies may be generalisable across clinical targets. However, due to the high heterogeneity observed in this review, the results should be interpreted cautiously. Future research should collect data about which population subgroups may benefit most from these interventions.

Like our review, previous systematic reviews have found no evidence that financial incentives improve the quality of healthcare, with evidence of small benefits at best, and urged caution when policy makers are considering introducing new incentives [ 143 , 144 ]. Although our study was not able to meta-analyse the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies, another review found the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) improved the quality of care in most included studies, despite many studies not adhering to the key method features [ 145 , 146 ].

Future implications

A limitation of this review was the quality of the included studies; many studies used a cluster design but did not account for clustering in their analysis. Studies should ensure that studies are powered to detect modest effects on behavioural outcomes, account for clustering and allow sufficient follow-up time to accrue sufficient events to detect changes in behavioural outcome as well as process outcomes.

No studies looked specifically at implementation strategies in remote consultations. As the delivery of primary care is changing, future research should consider whether these implementation strategies are effective across consultation modalities.

These results show that a broad suite of intervention strategies, and in particular multicomponent interventions may improve processes of preventive care. However, there is no evidence that these strategies improve patient outcomes through behaviour change, such as smoking cessation, increased physical activity, or reduced bodyweight or alcohol consumption. There is evidence that introducing population health interventions affect individuals’ attempts to change their behaviour and the success of those attempts to change [ 147 , 148 ]. Consequently, it may be helpful for policy makers to combine multicomponent implementation strategies to increase the delivery of preventive healthcare in primary care with population-level interventions to maximise health benefits.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

Quality improvement

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis

Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Excerpta Medica Database

PubMed Central

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

National Health Service

Cluster randomised trial

Cluster non-randomised trial

Randomised trial

Controlled before-after

Interrupted time series

Intracluster correlation coefficient

Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman

Confidence interval

Inverse variance heterogeneity

Body mass index

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Plan-Do-Study-Act

Zaninotto P, Head J, Steptoe A. Behavioural risk factors and healthy life expectancy: evidence from two longitudinal studies of ageing in England and the US. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6955.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–724.

Marteau TM, Rutter H, Marmot M. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ. 2021;372:n332.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Everest G, Marshall L, Fraser C, Briggs A. Addressing the leading risk factors for ill health A review of government policies tackling smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol use in England. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2022/Risk%20factors_Web_Final_Feb.pdf : The Health Foundation; 2022.

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Coker TR, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without cardiovascular disease risk factors: us preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2022;328(4):367–74.

Article Google Scholar

National institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Behaviour change: individual approaches https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49/chapter/recommendations2014

Maciosek MV, LaFrance AB, Dehmer SP, McGree DA, Xu Z, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Health Benefits and Cost-Effectiveness of Brief Clinician Tobacco Counseling for Youth and Adults. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(1):37–47.

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2021;325(3):265–79.

Purshouse RC, Brennan A, Rafia R, Latimer NR, Archer RJ, Angus CR, et al. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary care in England. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48(2):180–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2018;320(18):1899–909.

Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, Hood K, Christian-Brown A, Adab P, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2492–500.

Retat L, Pimpin L, Webber L, Jaccard A, Lewis A, Tearne S, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: cost-effectiveness analysis in the BWeL trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(10):2066–75.

Gc VS, Suhrcke M, Hardeman W, Sutton S, Wilson ECF, Very Brief Interventions Programme T. Cost-effectiveness and value of information analysis of brief interventions to promote physical activity in primary care. Value Health. 2018;21(1):18–26.

Posadzki P, Pieper D, Bajpai R, Makaruk H, Konsgen N, Neuhaus AL, et al. Exercise/physical activity and health outcomes: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1724.

Graham J, Tudor K, Jebb SA, Lewis A, Tearne S, Adab P, et al. The equity impact of brief opportunistic interventions to promote weight loss in primary care: secondary analysis of the BWeL randomised trial. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):51.

Mortimer F. The sustainable physician. Clin Med (Lond). 2010;10(2):110–1.

NHS England and NHS Improvment. The NHS Long Term Plan. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/2019 .

Laddu D, Ma J, Kaar J, Ozemek C, Durant RW, Campbell T, et al. Health Behavior Change Programs in Primary Care and Community Practices for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Risk Factor Management Among Midlife and Older Adults: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144(24):e533–49.

Rubio-Valera M, Pons-Vigués M, Martínez-Andrés M, Moreno-Peral P, Berenguera A, Fernández A. Barriers and Facilitators for the Implementation of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion Activities in Primary Care: A Synthesis through Meta-Ethnography. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89554.

Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Access to weight reduction interventions for overweight and obese patients in UK primary care: population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006642.

Nuffield Trust. Obesity; 2022. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/obesity .

NHS Digital. Health Survey for England, 2021 part 1 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2021/part-3-drinking-alcohol2022

Heath L, Ordonez-Mena JM, Aveyard P, Wherton J, Nicholson BD, Stevens R. How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the delivery of preventive healthcare? An interrupted time series analysis of adults in English primary care from 2018 to 2022. Prev Med. 2024;181:107923.

Litt J. RACGP Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice 9th edition. 2016.

Huibers L, Moth G, Carlsen AH, Christensen MB, Vedsted P. Telephone triage by GPs in out-of-hours primary care in Denmark: a prospective observational study of efficiency and relevance. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(650):e667–73.

Pearl R. Kaiser Permanente Northern California: current experiences with internet, mobile, and video technologies. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):251–7.

Heath LN, B.; Aveyard, P. Strategies to improve the implementation of preventative care in primary care: a systematic review. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022350912 : PROSPERO; 2022. Contract No.: CRD42022350912.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care. EPOC resources for review authors https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors2021

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021;74(9):790–9.

NHS England. Primary care services https://www.england.nhs.uk/get-involved/get-involved/how/primarycare/ [

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):Ii2–45.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

AHRQ Technical Reviews. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Owens DK, editors. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol 1: Series Overview and Methodology). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004.

Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, Turner L, Galipeau J, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2252–61.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Australia: Melbourne; 2024.

Google Scholar

Donabedian A. Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729.

Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Higgins JE, Li T, S. Li T. Chapter 23: Including variants on randomized trials. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 64. 2023.

Kottke TE, Brekke ML, Solberg LI, Hughes JR. A Randomized Trial to Increase Smoking Intervention by Physicians: Doctors Helping Smokers. Round I JAMA. 1989;261(14):2101–6.

Röver C, Knapp G, Friede T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):99.

SAR, Barendregt JJ, Khan S, Thalib L, Williams GM. Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials I: The inverse variance heterogeneity mode. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:130–8.

Ackermann RT, Deyo RA, LoGerfo JP. Prompting primary providers to increase community exercise referrals for older adults: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):283–9.

Adams A, Ockene JK, Wheller EV, Hurley TG. Alcohol counseling: physicians will do it. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(10):692–8.

Alageel S, Gulliford MC. Effect of the NHS Health Check programme on cardiovascular disease risk factors during 6 years’ follow-up: matched cohort study. The Lancet. 2018;392(Supplement 2):S17.

Alageel S, Gulliford MC. Health checks and cardiovascular risk factor values over six years’ follow-up: Matched cohort study using electronic health records in England. PLoS Med. 2019;16(7): e1002863.

Anderson P, Bendtsen P, Spak F, Reynolds J, Drummond C, Segura L, et al. Improving the delivery of brief interventions for heavy drinking in primary health care: outcome results of the Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Intervention (ODHIN) five-country cluster randomized factorial trial. Addiction. 2016;111(11):1935–45.

Anderson P, Manthey J, Llopis EJ, Rey GN, Bustamante IV, Piazza M, et al. Impact of Training and Municipal Support on Primary Health Care-Based Measurement of Alcohol Consumption in Three Latin American Countries: 5-Month Outcome Results of the Quasi-experimental Randomized SCALA Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(9):2663–71.

Asadi-Aliabadi M, Karimi SM, Mirbaha-Hashemi F, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Janani L, Babaee E, et al. Motivating non-physician health workers to reduce the behavioral risk factors of non-communicable diseases in the community: a field trial study. Arch Public Health. 2023;81(1):37.

Asadi-Aliabadi M, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Mirbaha-Hashemi F, Janani L, Babaee E, Karimi SM, et al. Evaluating the impact of results-based motivating system on noncommunicable diseases risk factors in Iran: Study protocol for a field trial. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021;35:66.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Higgins PS, Gassman RA, Gould BE. Training medical providers to conduct alcohol screening and brief interventions. Substance Abuse. 2004;25(1):17–26.

Baer HJ, Wee CC, Orav EJ, DeVito K, Burdick E, Williams DH, et al. Use of electronic health records for addressing overweight and obesity in rimary care: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2 SUPPL. 1):S452–3.

Bailey SR, Albert EL, Seeholzer EL, Lewis SA, Flocke SA. Sustained Effects of a Systems-Based Strategy for Tobacco Cessation Assistance. Am J Prev Med. 2023;64(3):428–32.

Balasubramanian BA, Lindner S, Marino M, Springer R, Edwards ST, McConnell KJ, et al. Improving Delivery of Cardiovascular Disease Preventive Services in Small-to-Medium Primary Care Practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(5):968–78.

Baldeon ME, Fornasini M, Flores N, Merriam PA, Rosal M, Zevallos JC, et al. Impact of training primary care physicians in behavioral counseling to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors in Ecuador. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e139.

Banerjee ES, Gambler A, Fogleman C. Adding obesity to the problem list increases the rate of providers addressing obesity. Fam Med. 2013;45(9):629–33.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bardach NS, Wang JJ, De Leon SF, Shih SC, Boscardin WJ, Goldman LE, et al. Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1051–9.

Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, Fleming L, Hollis JF, Hunt JS, et al. Provider feedback to improve 5A’s tobacco cessation in primary care: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):341–9.

Boston D, Larson AE, Sheppler CR, O’Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Hauschildt J, et al. Does Clinical Decision Support Increase Appropriate Medication Prescribing for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction? J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(5):777–88.

Butler CC, Simpson SA, Hood K, Cohen D, Pickles T, Spanou C, et al. Training practitioners to deliver opportunistic multiple behaviour change counselling in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2013;346(7901):10.

Campbell-Scherer DL, Asselin J, Osunlana AM, Ogunleye AA, Fielding S, Anderson R, et al. Changing provider behaviour to increase nurse visits for obesity in family practice: the 5As Team randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(2):E371.

Coleman T, Lewis S, Hubbard R, Smith C. Impact of contractual financial incentives on the ascertainment and management of smoking in primary care. Addiction. 2007;102(5):803–8.

Corelli RL, Merchant KR, Hilts KE, Kroon LA, Vatanka P, Hille BT, et al. Community pharmacy technicians’ engagement in the delivery of brief tobacco cessation interventions: Results of a randomized trial. Research in social & administrative pharmacy : RSAP. 2022;18(7):3158–63.

Cummings SR, Coater TJ, Richard RJ, Hansen B, Zahnd EG, VanderMartin R, et al. Training physicians in counseling about smoking cessation. A randomized trial of the “Quit for Life” program. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(8):640–7.

Dubey V, Mathew R, Iglar K, Moineddin R, Glazier R. Improving preventive service delivery at adult complete health check-ups: the Preventive health Evidence-based Recommendation Form (PERFORM) cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:44.

Evins AE, Cather C, Maravic MC, Reyering S, Pachas GN, Thorndike AN, et al. A Pragmatic Cluster-Randomized Trial of Provider Education and Community Health Worker Support for Tobacco Cessation. Psychiatr Serv. 2023;74(4):365–73.

Fichera E, Gray E, Sutton M. How do individuals’ health behaviours respond to an increase in the supply of health care? Evidence from a natural experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:170–9.

Fiore M, Adsit R, Zehner M, McCarthy D, Lundsten S, Hartlaub P, et al. An electronic health record-based interoperable eReferral system to enhance smoking Quitline treatment in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2019;26(8–9):778–86.

Flocke SA, Albert EL, Lewis SA, Love TE, Rose JC, Kaelber DC, et al. A cluster randomized trial evaluating a teachable moment communication process for tobacco cessation support. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):85.

Flocke SA, Seeholzer E, Lewis SA, Gill IJ, Rose JC, Albert E, et al. 12-Month Evaluation of an EHR-Supported Staff Role Change for Provision of Tobacco Cessation Care in 8 Primary Care Safety-Net Clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3234–42.

Funk M, Wutzke S, Kaner E, Anderson P, Pas L, McCormick R, et al. A multicountry controlled trial of strategies to promote dissemination and implementation of brief alcohol intervention in primary health care: findings of a World Health Organization collaborative study. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(3):379–88.

Girvalaki C, Papadakis S, Vardavas C, Pipe AL, Petridou E, Tsiligianni I, et al. Training General Practitioners in Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment: An Evaluation of the Tobacco Treatment Training Network in Crete (TiTAN-Crete) Intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(6):888–97.

Goodfellow J, Agarwal S, Harrad F, Shepherd D, Morris T, Ring A, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a tailored intervention to improve the management of overweight and obesity in primary care in England. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):77.

Grant RW, Schmittdiel JA, Neugebauer RS, Uratsu CS, Sternfeld B. Exercise as a vital sign: a quasi-experimental analysis of a health system intervention to collect patient-reported exercise levels. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(2):341–8.

Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, Ukoumunne OC, Narring F, Broers B. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal. 2014;186(8):E263–72.

Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, van Driel M, Russell G, Mazza D, et al. An Australian general practice based strategy to improve chronic disease prevention, and its impact on patient reported outcomes: evaluation of the preventive evidence into practice cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–14.

Haskard KB, White MK, Williams SL, DiMatteo MR, Rosenthal R, Goldstein MG. Physician and patient communication training in primary care: effects on participation and satisfaction [corrected] [published erratum appears in HEALTH PSYCHOL 2009 Mar; 28(2):263]. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):513–22.

Hilbink M, Voerman G, van Beurden I, Penninx B, Laurant M. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored primary care program to reverse excessive alcohol consumption. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):712–22.

Houston TK, Delaughter KL, Ray MN, Gilbert GH, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of a web-assisted tobacco quality improvement intervention of subsequent patient tobacco product use: a National Dental PBRN study. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:13.

Houston TK, Sadasivam RS, Allison JJ, Ash AS, Ray MN, English TM, et al. Evaluating the QUIT-PRIMO clinical practice ePortal to increase smoker engagement with online cessation interventions: a national hybrid type 2 implementation study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):154.

Houston TK, Sadasivam RS, Ford DE, Richman J, Ray MN, Allison JJ. The QUIT-PRIMO provider-patient Internet-delivered smoking cessation referral intervention: a cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial: study protocol. Implement Sci. 2010;5:87.

Hudmon KS, Corelli RL, de Moor C, Zillich AJ, Fenlon C, Miles L, et al. Outcomes of a randomized trial evaluating two approaches for promoting pharmacy-based referrals to the tobacco quitline. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58(4):387–94.

Joseph AM, Nancy JA, Larry CA, Sean MN, Richard JS, Pieper CF, et al. Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Intervention to Implement Smoking Guidelines in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers: Increased Use of Medications without Cessation Benefit. Med Care. 2004;42(11):1100–10.

Jumbe S, Madurasinghe VW, James WY, Houlihan C, Jumbe SL, Yau T, et al. STOP- a training intervention to optimise treatment for smoking cessation in community pharmacies: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):1–14.

Kaner E, Lock C, Heather N, McNamee P, Bond S, Kaner E, et al. Promoting brief alcohol intervention by nurses in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):277–84.

Keller S, Donner-Banzhoff N, Kaluza G, Baum E, Basler HD. Improving physician-delivered counseling in a primary care setting: lessons from a failed attempt. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2000;13(3):387–97.

Kowitt SD, Goldstein AO, Cykert S. A heart healthy intervention improved tobacco screening rates and cessation support in primary care practices. J Prev. 2022;43(3):375–86.

Lee AK, Bobb JF, Richards JE, Achtmeyer CE, Ludman E, Oliver M, et al. Integrating Alcohol-Related Prevention and Treatment Into Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Implementation Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(4):319–28.

Lennox AS, Bain N, Taylor RJ, McKie L, Donnan PT, Groves J. Stages of Change training for opportunistic smoking intervention by the primary health care team. Part I : randomised controlled trial of the effect of training on patient smoking outcomes and health professional behaviour as recalled by patients. Health Educ J. 1998;57(2):140–9.

Linder JA, Rigotti NA, Schneider LI, Kelley JHK, Brawarsky P, Haas JS. An electronic health record-based intervention To improve tobacco treatment in primary care a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):781–7.

Little SJ, Hollis JF, Fellows JL, Snyder JJ, Dickerson JF. Implementing a tobacco assisted referral program in dental practices. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(3):149–55.

Malta MB, Carvalhaes MA, Takito MY, Tonete VL, Barros AJ, Parada CM, et al. Educational intervention regarding diet and physical activity for pregnant women: changes in knowledge and practices among health professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):175.

McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, Knight J, Bowman JA, Wolfenden L, et al. Increasing preventive care by primary care nursing and allied health clinicians: a non-randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):424–34.

McRobbie H, Hajek P, Feder G, Eldridge S. A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a brief training session to facilitate general practitioner referral to smoking cessation treatment. Tob Control. 2008;17(3):173–6.

Mejia R, Pérez Stable EJ, Kaplan CP, Gregorich SE, Livaudais-Toman J, Peña L, et al. EFfectiveness of an intervention to teach physicians how to assist patients to quit smoking in Argentina. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1101–9.

Milch CE, Edmunson JM, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Selker HP. Smoking cessation in primary care: a clinical effectiveness trial of two simple interventions. Prev Med. 2004;38(3):284–94.

Minian N, Baliunas D, Noormohamed A, Zawertailo L, Giesbrecht N, Hendershot CS, et al. The effect of a clinical decision support system on prompting an intervention for risky alcohol use in a primary care smoking cessation program: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):85.

Minian N, Baliunas D, Zawertailo L, Noormohamed A, Giesbrecht N, Hendershot CS, et al. Combining alcohol interventions with tobacco addictions treatment in primary care-the COMBAT study: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):65.

Minian N, Lingam M, Moineddin R, Thorpe KE, Veldhuizen S, Dragonetti R, et al. The Impact of a Clinical Decision Support System for Addressing Physical Activity and Healthy Eating During Smoking Cessation Treatment: Hybrid Type I Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(9):e37900.

Moore H, Greenwood D, Gill T, Waine C, Soutter J, Adamson A. A cluster randomised trial to evaluate a nutrition training programme. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(489):271–7.

Moore H, Summerbell C, Vail A, Greenwood DC, Adamson AJ. The design features and practicalities of conducting a pragmatic cluster randomized trial of obesity management in primary care. Stat Med. 2001;20(3):331–40.

O’Donnell A, Angus C, Hanratty B, Hamilton FL, Petersen I, Kaner E. Impact of the introduction and withdrawal of financial incentives on the delivery of alcohol screening and brief advice in English primary health care: an interrupted time–series analysis. Addiction. 2020;115(1):49–60.

Olano-Espinosa E, Matilla-Pardo B, Minué C, Antón E, Gómez-Gascón T, Ayesta FJ. Effectiveness of a health professional training program for treatment of tobacco addiction. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1682–9.

Ornstein SM, Miller PM, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Nemeth LS, Nizetert PJ. Integration and sustainability of alcohol screening, brief intervention, and pharmacotherapy in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(4):598–604.

Patwardhan PD, Chewning BA. Effectiveness of intervention to implement tobacco cessation counseling in community chain pharmacies. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 2012;52(4):507–14.

Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Marani S, Foxhall L, Ford KH, Luca NS, et al. Engaging physicians and pharmacists in providing smoking cessation counseling. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1640–6.

Ribeiro C. The family medicine approach to alcohol consumption detection and brief interventions in primary health care. Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2011;24(SUPPL.2):355–68.

Rieckmann T, Renfro S, McCarty D, Baker R, McConnell KJ. Quality Metrics and Systems Transformation: Are We Advancing Alcohol and Drug Screening in Primary Care? Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1702–26.

Rindal DB, Kottke TE, Jurkovich MW, Asche SE, Enstad CJ, Truitt AR, et al. Findings and Future Directions from a Smoking Cessation Trial Utilizing a Clinical Decision Support Tool. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2022;22(3): 101747.

Rosário F, Vasiljevic M, Pas L, Angus C, Ribeiro C, Fitzgerald N. Efficacy of a theory-driven program to implement alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary health-care: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2022;117(6):1609–21.

Rosário F, Vasiljevic M, Pas L, Fitzgerald N, Ribeiro C. Implementing alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary health care: study protocol for a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2019;36(2):199–205.

Rose HL, Miller PM, Nemeth LS, Jenkins RG, Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, et al. Alcohol screening and brief counseling in a primary care hypertensive population: a quality improvement intervention. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2008;103(8):1271–80.

Roski J, Jeddeloh R, An L, Lando H, Hannan P, Hall C, et al. The impact of financial incentives and a patient registry on preventive care quality: increasing provider adherence to evidence-based smoking cessation practice guidelines. Prev Med. 2003;36(3):291–9.

Rossom RC, Crain AL, O’Connor PJ, Waring SC, Hooker SA, Ohnsorg K, et al. Effect of Clinical Decision Support on Cardiovascular Risk Among Adults With Bipolar Disorder, Schizoaffective Disorder, or Schizophrenia: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(3):e220202.

Rossom RC, O’Connor PJ, Crain AL, Waring S, Ohnsorg K, Taran A, et al. Pragmatic trial design of an intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in people with serious mental illness. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;91:105964.

Rothemich SF, Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Burgett AE, Flores SK, Marsland DW, et al. Effect on Cessation Counseling of Documenting Smoking Status as a Routine Vital Sign: An ACORN Study. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(1):60.

Ruf D, Berner M, Kriston L, Lohmann M, Mundle G, Lorenz G, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of dissemination strategies of an online quality improvement programme for alcohol-related disorders. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 2010;45(1):70–8.

Saitz R, Horton NJ, Sullivan LM, Moskowitz MA, Samet JH, Saitz R, et al. Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: a cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention. The screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):372–49.

Schwartz MD, Jensen AE, Wang B, Bennett K, Dembitzer A, Strauss S, et al. The use of panel management assistants to improve smoking cessation and hypertension management by VA primary care teams: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(SUPPL. 1):S234–5.

Sinclair HK, Bond CM, Lennox AS, Silcock J, Winfield AJ, Donnan PT. Training pharmacists and pharmacy assistants in the stage-of-change model of smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial in Scotland. Tob Control. 1998;7(3):253.

Sohanpal R, Jumbe S, James WY, Steed L, Yau T, Rivas C, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Smoking Treatment Optimisation in Pharmacies (STOP) intervention: Protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):337.

Sturgiss E, Advocat J, Lam T, Nielsen S, Ball L, Gunatillaka N, et al. Multifaceted intervention to increase the delivery of alcohol brief interventions in primary care: a mixed-methods process analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2023;73(735):e778–88.

Sturgiss E, Gunatillaka N, Ball L, Lam T, Nielsen S, O’Donnell R, et al. Embedding brief interventions for alcohol in general practice: a study protocol for the REACH Project feasibility trial. Bjgp Open. 2021;5(4):1–7.

Szatkowski L, Aveyard P. Provision of smoking cessation support in UK primary care: impact of the 2012 QOF revision. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(642):e10–5.

Twardella D, Brenner H. Effects of practitioner education, practitioner payment and reimbursement of patients’ drug costs on smoking cessation in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. Tob Control. 2007;16(1):15–21.

Unrod M, Smith M, Spring B, DePue J, Redd W, Winkel G. Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based, tailored intervention to increase smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):478–84.

van Beurden I, Anderson P, Akkermans RP, Grol RPTM, Wensing M, Laurant MGH. Involvement of general practitioners in managing alcohol problems: a randomized controlled trial of a tailored improvement programme. Addiction. 2012;107(9):1601–11.

Van Lieshout J, Huntink E, Koetsenruijter J, Wensing M. Tailored implementation of cardiovascular risk management in general practice: A cluster randomized trial. Implementation Science. 2016;11:115.

Verbiest MEA, Crone MR, Scharloo M, Chavannes NH, van der Meer V, Kaptein AA, et al. One-hour training for general practitioners in reducing the implementation gap of smoking cessation care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(1):1–10.

Wadland WC, Holtrop JS, Weismantel D, Pathak PK, Fadel H, Powell J. Practice-based referrals to a tobacco cessation quit line: assessing the impact of comparative feedback vs general reminders. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):135–42.

Wadlin J, Ford DE, Albert MC, Wang NY, Chander G. Implementing an EMR–Based Referral for Smoking Quitline Services with Additional Provider Education, a Cluster-Randomized Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2438–45.

Welzel FD, Bär J, Stein J, Löbner M, Pabst A, Luppa M, et al. Using a brief web-based 5A intervention to improve weight management in primary care: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):61.

Welzel FD, Stein J, Pabst A, Luppa M, Kersting A, Bluher M, et al. Five A’s counseling in weight management of obese patients in primary care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial (INTERACT). BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):97.

Wiggers J, McElwaine K, Freund M, Campbell L, Bowman J, Wye P, et al. Increasing the provision of preventive care by community healthcare services: a stepped wedge implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2017;12:1–14.

Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Farmer MM, Chernof BA, Mittman BS, Lanto AB, et al. Targeting primary care referrals to smoking cessation clinics does not improve quit rates: implementing evidence-based interventions into practice. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(5 Pt 1):1637–61.

Young JM, D’Este C, Ward JE, Young JM, D’Este C, Ward JE. Improving family physicians’ use of evidence-based smoking cessation strategies: a cluster randomization trial. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):572–83.

Baer HJ, Wee CC, DeVito K, Orav EJ, Frolkis JP, Williams DH, et al. Design of a cluster-randomized trial of electronic health record-based tools to address overweight and obesity in primary care. Clin Trials. 2015;12(4):374–83.

Coleman T. Do financial incentives for delivering health promotion counselling work? Analysis of smoking cessation activities stimulated by the quality and outcomes framework. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):167–72.

Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549.

Rubinsky AD, Dawson DA, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. AUDIT-C Scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(8):1380–90.

Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF. A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: Past issues and future directions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(6):578–86.

Konnyu KJ, Yogasingam S, Lépine J, Sullivan K, Alabousi M, Edwards A, et al. Quality improvement strategies for diabetes care: Effects on outcomes for adults living with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;5(5):Cd014513.

Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, Hamid JS, Cogo E, Strifler L, et al. Quality improvement strategies to prevent falls in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(3):337–46.

Manalili K, Lorenzetti DL, Egunsola O, O’Beirne M, Hemmelgarn B, Scott CM, et al. The effectiveness of person-centred quality improvement strategies on the management and control of hypertension in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(2):260–77.

Mandavia R, Mehta N, Schilder A, Mossialos E. Effectiveness of UK provider financial incentives on quality of care: a systematic review. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2017;67(664):e800–15.

Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, Willenberg L, Naccarella L, Furler J, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD008451.

Knudsen SV, Laursen HVB, Johnsen SP, Bartels PD, Ehlers LH, Mainz J. Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):683.

Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):Cd008743.

Wyper GMA, Mackay DF, Fraser C, Lewsey J, Robinson M, Beeston C, et al. Evaluating the impact of alcohol minimum unit pricing on deaths and hospitalisations in Scotland: a controlled interrupted time series study. Lancet. 2023;401(10385):1361–70.

Nagelhout GE, de Vries H, Boudreau C, Allwright S, McNeill A, van den Putte B, et al. Comparative impact of smoke-free legislation on smoking cessation in three European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):4–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Corina Cheeks for her valuable PPI perspective and Nia Roberts for her search strategy expertise.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [225494/Z/22/Z]. PA is an NIHR senior investigator and funded by NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, and NIHR Oxford and Thames Valley Applied Research Collaboration.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Radcliffe Primary Care Building, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK

Laura Heath, Richard Stevens, Brian D. Nicholson, Joseph Wherton, Min Gao, Caitriona Callan, Simona Haasova & Paul Aveyard

Department of Marketing, University of Lausanne, Quartier UNIL-Chamberonne, Lausanne, Quartier, CH-1015, Switzerland

Simona Haasova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LH, RS, BN and PA planned the study. LH, RS, PA, MG, SH and CC conducted the analysis. RS provided senior statistical support. BN, JW and PA provided supervisory support. LH wrote the initial draft. All authors commented on the final reporting of the work. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Twitter handles

Laura Heath: @laurahheath.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Laura Heath .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate..

Not applicable.

Consent for publication.

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: database search strategy., sadditional file 2: imputed calculations., 12916_2024_3588_moesm3_esm.docx.

Additional file 3: Figures S1-S7. FigS1 – Meta-analysis summary diamonds as random effects (main analysis), Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) and inverse variance heterogeneity (IVhet) models for process outcomes. FigS2 - Meta-analysis summary diamonds as random effects (main analysis), Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) and inverse variance heterogeneity model (IVhet) models for behavioural outcomes. FigS3 - Random effects meta-analysis summary diamonds excluding studies at high risk of bias and those that required data imputation for process outcomes. FigS4 - Random effects meta-analysis summary diamonds excluding studies at high risk of bias and those that required data imputation for behavioural outcomes. FigS5 - Random effects meta-analysis of behavioural outcomes, excluding Moore 2003, Welzel 2021 and Goodfellow 2016. FigS6 - Random effects meta-analysis summary diamonds of health behaviour subgroups for process outcomes. FigS7 - Random effects meta-analysis summary diamonds of health behaviour subgroups for behavioural outcomes.

Additional file 4: Stata code.

Additional file 5: table s1 - characteristics of included studies., additional file 6: prisma 2020 for abstracts checklist., additional file 7: prisma 2020 checklist., additional file 8: table s1 - prediction interval calculation and interpretation., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Heath, L., Stevens, R., Nicholson, B.D. et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of preventive care in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 22 , 412 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03588-5

Download citation

Received : 18 February 2024

Accepted : 27 August 2024

Published : 27 September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03588-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Primary care

- Implementation

- Physical activity

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search